The Blinds

George Sparling | Mike S. Young

Published on 2013-12-06

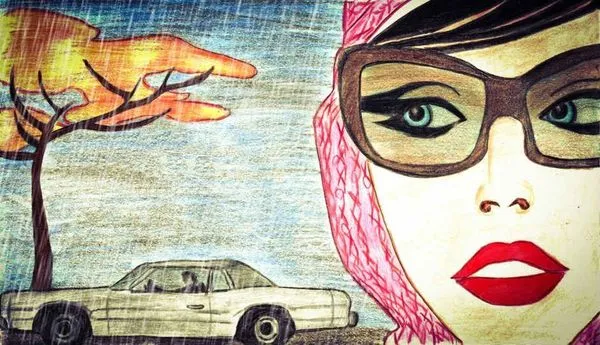

After work, ever since he recently bought the house, Mercer always sat in front of the window at evening twilight, viewing the passing neighborhood scene through Venetian blinds. The former tenants left the blinds behind. Mercer hadn’t wanted passersby to think he spied on them or was voyeuristic. Mercer called what happened special effects when he slanted the slats at forty-five degree angles.

He enjoyed how the setting sun traveled on its path below the horizon, observing each dip incrementally lower, until night. Not dark enough to flick on the lights, the sun’s center was now six degrees below the local horizon. It was called official twilight. He saw some stars and Venus. He needed lights to read but chose to sit in dimness.

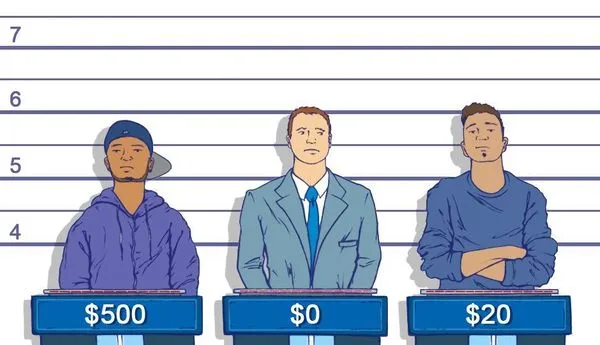

Between official twilight and when the sun was still visible came the special effects. He no longer required bifocals; his vision had increased ten-fold. He eyed a heart-shaped pin on a woman’s breast, spotting every diamond’s facet and their flaws. He now read lips of pedestrians talking on smartphones. His eyes lit up when he observed the man across the street, shades drawn, his bone shooting into the woman’s mouth, she married, living next door. He heard the man’s pleasure-moan. He also heard each word on the police car radio as it patrolled past the blinds.

Time seemed to expand as Mercer felt stronger, though small framed. He stood up and clean and jerked the hundred-pound barbell five times in succession, something he couldn’t do before, fearful of a hernia. He stroked his erection for what seemed forever, withholding discharge for as long as he wanted. Before it was ten minutes and out. He no longer needed to look at the clock or watch as if he imbibed time seated before the blinds. He knew within thirty seconds the time without looking at his watch.

He tested his increased powers by raising the blinds and found that hadn’t given him the tingling, warm sensation he felt in his eyes or how his mental alertness shifted into the highest gear of the day. His job entailed fastidious intellectual labor, but through the slats he heard his brain click into a higher-geared intelligence. Usually he was fatigued after work but not anymore, thanks to these blinds. Divorced, he was in a transitional phase; neither interested in seeking out women nor searching for a sexual partner. He craved more than she could give. She was subtraction, he addition. This house bought after the divorce he lived by himself withdrawn from social mix masters and relationship blenders.

He speed read now, having finished 800-page novels in a few hours. He loved music of all kinds, especially Shostakovich’s symphonies. Previously he found the atonality incomprehensible, but listened anyway, appreciating the grimness of Shostakovich’s life and art under Stalin, how dictatorship left Dmitri alone among Soviet composers.

And how he lived alone, lifted above normal persons’ imaginations, not unlike Dmitri. His auditory sense vastly improved. Mercer heard tubas for the first time in Shostakovich’s symphonies. After work, like a devout religious man, Mercer sat in front of the blinds, rejuvenated, homing in on the tuba.

The traffic intrigued him, how vehicles now crept more slowly; he saw clearly drivers’ faces, shoulders, and hands. Every driver male or female, all so handsome, pretty, attractive, inviting, lissome. Now, more alert to his needs, he sensed their charm as if they would note his wife’s absence, perhaps inserting themselves into his new living quarters. Now, sexually attuned, the special effects supplied his new life with ample room for contradictions.

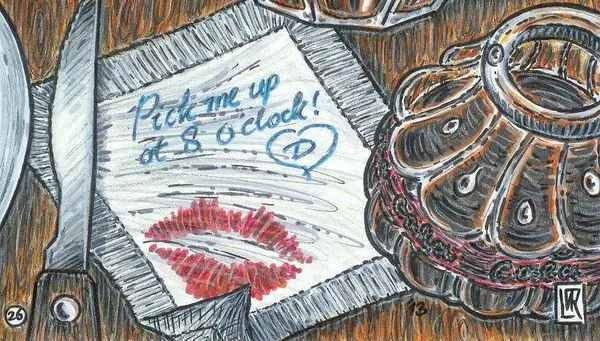

Through the slats, each driver seemed adorable. When they would drop off or pick up friends or parked in driveways he yearned for them, his voice singing in Italian, a language he hadn’t ever learned. He sang Verdi arias, his fingers clenching and unclenching—gimme, gimme, they said. Promoted since the blinds, his paycheck increased, his work-world senses gifted him with powers he had once thought unimaginable.

At dusk, he felt more than simply drawn to his rocking chair. It had now become an addiction, one that wouldn’t let go. The tubas dominated the Shostakovich symphonies to an extent that the other instruments had vanished. He knew tubas played a part but hearing only tubas unnerved him. The drivers shifted from persons with heads, arms, fingers, and shoulders to large bell tubas, the drivers’ fingers on the buttons rather than the steering wheel. Tubing, perhaps sixteen feet of curved brass finished the drivers’ bodies. Mercer saw tubas emerge from cars, walking to their homes as instruments. He had a jones for Shostakovich’s symphonies, orchestras now comprised solely of tubas. What happened to the other instruments? he asked out loud.

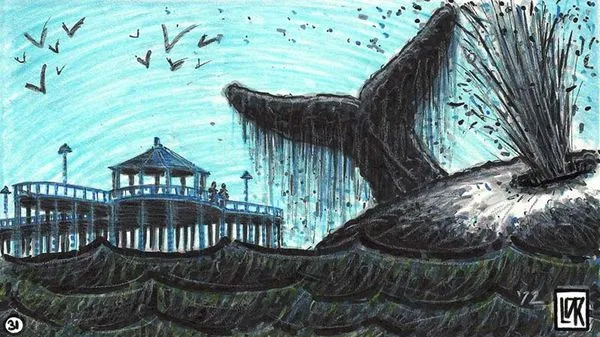

The next dusk Mercer saw, instead of polished tubas, parasitic worms, Helminths. They were huge, and squeezed themselves from within the tubas’ bells, brass bursting apart, the tubas birthing gigantic roundworms. In the neighborhood, former persons looked like white worms, mouths agape, their flat heads, how their upright movements defied gravity.

Something crawled into Mercer’s ear. The slanted blinds left him with heightened powers of touch. It was when Mercer felt objects that he understood through tactility the nature of that object, its quirks and molecular structure as well as its reason for existence. As it crawled inside, the worm bore through the outer portion of the cerebrum, into the cortex, and then entered the sensory and associative areas.

Imagine he had gotten inside a writer’s mind, much as the worm had entered his. Mercer’s ability to infiltrate, say, the life of a writer at the computer, key-stroking letters, words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, the entire work, Mercer’s fingertips might absorb the subject matter, moods, plot, characters, symbolism, and themes of the work. Like- wise, by tracing the worm’s length with his little finger as the worm snuck into his ear, he knew it was a miniature variety of the larger worm-people outside as seen through the blinds.

His powers diminished and eyesight darkened, he put on his glasses seeing only hazy outlines. His muscles atrophied, just seeing the outline of the barbell nauseated him. Imagining the writer metaphor, he couldn’t recreate now.

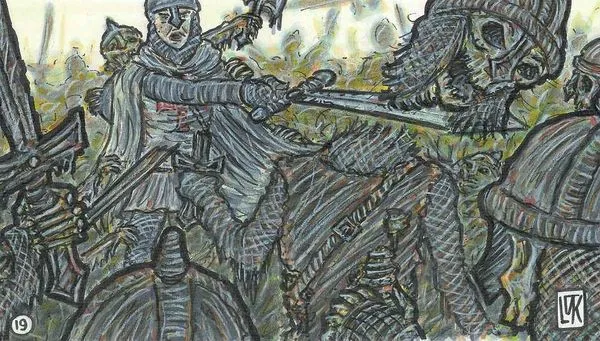

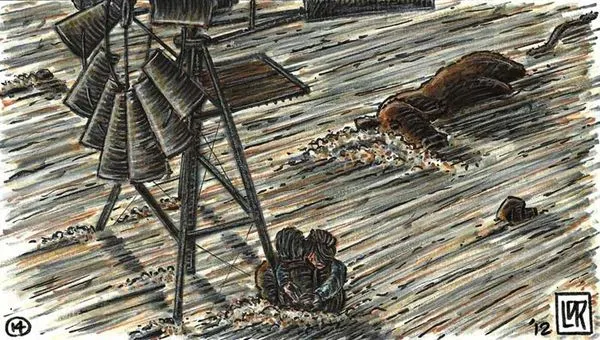

He moved upright from the rocker, shuffled incrementally, his human power source drained onto the carpet, primordial soup sopping his living room. He nicked the rocker’s leg with what had been his foot, now the roundworm’s tail, heaved slowly into the blinds, and crushed though the window. Hundreds of shards of glass pricked the roundworm’s epidermis, Mercer encased inside, the worm’s size greater than the six-footer he was, also bled.

Both the worm and Mercer were covered in blood, spouting from all points of his naked body. The worm shook as a dog shaking water off its fur, sending sparkles of Mercer’s red droplets mingled with worm mucus through the moonlit night.

The few pedestrians he saw were large roundworms. Without the blinds, they squirmed along, faceless, but with teeth that could eat out human intestinal tracts. Drivers steered with snouts, managing not to crash. Mercer manipulated the worm and together slowly skidded into his house. Mercer squatted on the living room carpet. Parasitic, having an opening at both ends, Mercer-worm hoped for a complete shit. Thinking he shit the roundworm out, instead the worm shat him out.

He slept in bloody sheets that night. Next morning, after a long shower, he examined the stigmata marks. They would heal, he hoped. Scar tissue might remain, but such a small price to pay. Dressed, he looked at glass fragments stuck out at ugly angles in the window frame. The blinds lay twisted but intact on the lawn. He scanned the neighborhood from the yard and saw real people.

He played Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony honoring the citizens’ resistance to the Nazi siege. In sympathy with all victims under oppression, nevertheless he decided to donate the blinds to a thrift store. Recycled, another person should have the same experience he had. If bitterness was the only lingering special effect, he could live with that.