Too Far

Townsend Walker | Kristy Lankford

Published on 2015-06-15

She sits on a wooden bench in the public garden, a young woman in a long grey dress, legs crossed, elbow on her left knee, chin on her gloved fist. Two books with worn yellow covers lie next to her, and beside them, a straw boater with a black ribbon around the crown. Her forward posture suggests some impatience. The person she waits for has been away. Her broad set and lidded eyes focus on the alley of cypress. The trees are overgrown. No one has trimmed them for a decade and now they shade the path. The figure that comes into view appears to be Albert. Some six months ago she’d met him at a luncheon arranged by a mutual friend. Since, they’ve been together with increasing frequency. She has come to believe, from his intimations, from the hints of his friends, from the manner in which he takes her arm, that she will soon be invited to meet his mother, The Duchess. She allows herself to imagine what the future might hold. Perhaps a Thursday salon with his university colleagues, travel to Africa and India to observe the creatures he’s often mentioned, and the end to worry.

Albert wears a dove grey tailored suit and light blue cravat. A gap in the trees allows the sun to bounce off his Panama hat, creating a glow around his head. As he moves into shadow, there appears to be something different. His head is larger, bulbous, the head of a rhinoceros.

“Vivian, how kind of you to wait for me. I hope you have not been here long.”

The voice sounds like Albert’s. The demeanor is his. The outstretched hand is his. But a curved horn resides where his nose was. His eyes are no longer faded blue, but large, round and dark. And those deep wrinkles about the eyes and mouth.

“Not at all. I’ve been dipping into my book, Kipling. This seems the season for him.”

“I’ve come with Ovid. The day promises to be interesting.”

Sitting side by side on the bench he cannot fully turn his head toward her as he once did, but in all other respects his movements are the same. He parts his thick lips and asks her what she would like to do this afternoon. She suggests a nearby tea room. As they walk, she opens her parasol, ostensibly to shade them from the sun. In fact, to shield his head from view when other couples approach. She doesn’t want people to think ill of him in this state. But how will he drink his tea?

In the tea salon she finds a corner table where they will be little observed.

“Vivian, you’ve been kind to feign this were all terribly normal. I do not know how to excuse this appearance, but truly it was the only way.”

“The only way?”

“Last week, my father insisted I join the family business, we’re bankers you know.” Albert recounts the year he spent with his father before going on to study philosophy. “My god, the people one is forced to deal with in finance. Unspeakable—all numbers, nothing enlightening, no higher thoughts.” He shutters with the memory. “I had to do something.”

“This is deliberate then, your rhinoceros head?”

“After he saw it, Father said that under no condition would he allow me in the bank. He demanded I leave the house, forthwith. Not that he is cruel, he provided a generous annuity.”

He leans over the table and laps up some tea with his small pink tongue, splattering half of the liquid on the table. “Oh dear.”

“It’s all right, you’ll become accustomed.”

We must go away. Somewhere safe. Close to his kind. To Africa? No, India, one horn. Otherwise what will I do? Another three months and he will know I have no income. I cannot sustain appearances any longer. The Bolivian railway bonds, her father had put much faith (and savings) into, collapsed two years before his death.

“I visited a woman in a small hamlet near Shrewsbury who specializes in therianthropy. She helped me with the transformation—potions and a special diet.”

“But us, what of us?” She leans across the table, though able to look pleadingly into only one of his soft brown eyes.

“I could never subject you …”

“Albert, hush. I cannot imagine a future without you.” She looks at his head more closely—the silver brown complexion, the beak-like mouth, the heavy folds of skin, then his body—one small manicured hand resting on the table, and his lithe frame.

“India. That is where we must go. I have read that two of the most popular Hindu gods have animal heads and human bodies—Ganesh and Hanuman. You would be welcomed, even worshiped, there.”

“But what of you? What would you do?”

“I would tend to your needs, bear your children: those things a loving wife does.”

Large tears drop from Albert’s eyes, dousing the table. “You would do that for me?”

She takes his hands in hers and leans forward to kiss him. People at the other tables fled when they first walked in. Now, the waiters and barmen do the same. “She’s kissing it, she’s kissing it, the horror of it all,” gasping as they race to the door.

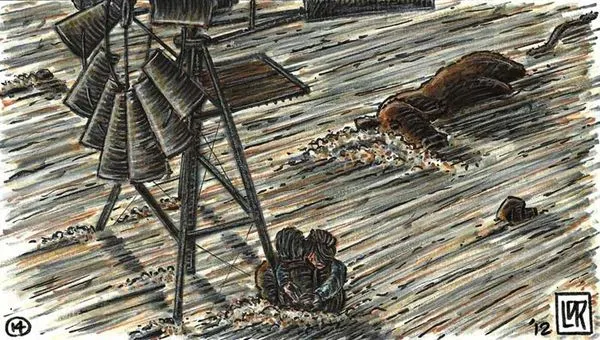

Albert looks down to the hand that has been resting in his lap. “I wish, with all my heart I wish, but I fear things have gone too far. He holds out the hand. It is turning leathery and silver brown, the fingers are merging, the nails becoming hooves. The cloth of his suit jacket is near to splitting. “I must go now, for your sake.”

He rises awkwardly form the café chair and lumbers to the door. Through the glass window she watches him drop to the ground and shuffle away on all fours.