How Wars Begin

Published on 2017-04-26

Victor’s back was against the sofa’s backrest, his feet flat on the floor, his knees bent, his hands on his lap, the epitome of well-educated patience, his mother’s eyes stunned with pride: Victor usually didn’t show mature enthusiasm. Had his attitude changed?

The teacher knew this was impossible. But the mother dreamed.

The teacher’s indifference towards Victor was reciprocated, Victor glad the teacher didn’t want to teach, the teacher happy that Victor didn’t want to learn, both delighted with mutual indifference.

Victor’s mother left the room, closing the door.

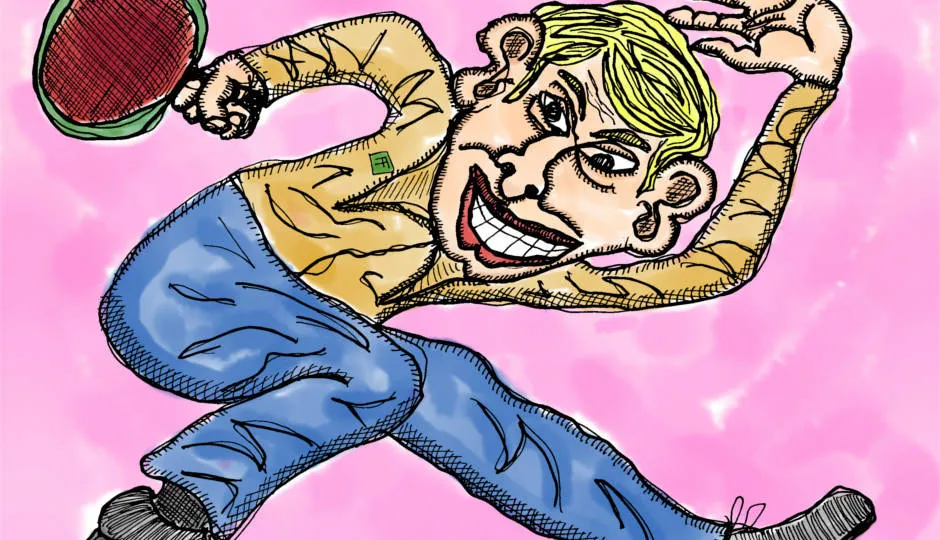

Victor smiled. The teacher had never seen such a cruel grin.

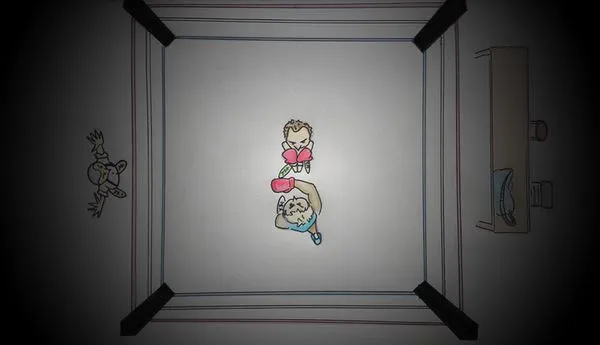

Victor’s body had been covering table-tennis bats. He’d left the ball hidden behind a cushion.

“Too loud,” the teacher whispered, as Victor tapped the ball with a bat.

Victor nodded approvingly as the teacher ripped sheets from the notebook that Victor had left on the table. The teacher made a paper ball. Victor tapped it up and down and said: “Perfecto.”

Victor spread a blanket across the floor to make a net. The tennis began. The teacher made comments in English to create the impression that a class was going on. Victor kept the score. The rallies halted when the paper ball landed in out-of-the-way places; or when Victor gave vent to his destructive impulses by unleashing overhead smashes, one hitting the teacher’s forehead, Victor’s gasping laugh, with his ape-like grimace, like a chimpanzee being tickled.

Eventually, Victor asked: “What time is it?”

The teacher shared Victor’s interest in time’s evaporation. The teacher picked up his phone, hoping that copious time had elapsed.

“A quarter to seven,” he said.

Victor was plonked on the sofa, his left leg on a coffee table.

“Mama mia,” he hissed.

Time without technology exposes an adolescent’s emotional state: in Victor’s case that state wasn’t a good state to be in.

The teacher smacked the paper ball at Victor who smiled when it struck Victor’s lower-abdomen region. Victor fell back onto the sofa, tapping the paper ball up and down with his bat. All enthusiasm left him, the paper ball falling onto the floor, Victor’s body like flesh rubber, his legs splayed, his mouth gaping, his eyes dark, the room possessed of an asteroid’s lifelessness, time without dynamism.

Victor smacked the paper ball out the window. They were two storeys above the footpath on a busy road. Victor’s monkey giggle resembled an asthma sufferer experiencing breathing difficulties, the paper ball having struck a pedestrian on the head.

Victor smashed a squash ball out the window; the ball, landing in front of a car at traffic lights, bounced and hit the car’s windscreen. Victor, like a delighted sniper, giggled, his crazed grimace, of malevolent hilarity, making the teacher think: He won’t be laughing in the hamburger joint he’ll be working in — that’s assuming he’s not in prison.

Victor started looking for things in the bowls on the table, his hands rattling pens, coins, and marbles, paper-clips selected to be launched out the window.

Victor perched a leg on the sofa’s armrest, the foot pointing back towards the teacher, the teacher checking the time and thinking: Sixty per cent of this absurdity has gone. Please forty percent hurry up.

Victor threw the paper-clips out the window. He then hid behind a curtain, sniggering with his ape-like gasping while observing his victim’s confusion.

Then he leapt back across the room to get a coin, his laughter sounding like “Oooahh!”

Monkey laughter, the teacher thought.

Victor hurled the coin before leaping behind the curtain, his head shaking with laughter, gasping hisses being pumped from his mouth.

He then crossed the room and selected a pen. Back on the sofa, his stillness had the focused poise of a predator. Traffic noise came through the window. A plant shook after Victor had bumped it in his enthusiasm to return to his vantage point, the teacher saying: “The sniper of Mendéz Alvaro.”

Something had to be said.

The sniping had despatched twenty minutes, a pretentious tone of admiration in the teacher’s voice, boredom’s debilitating force corrupting them both.

Victor hurled the pen and laughed; he dashed back to the table; he rattled through things in an ashtray, selecting a steel toy car, the teacher not surprised by Victor’s vileness.

This monkey, the teacher thought, will one day arouse the interest of a higher force and that day may in fact be today.

Victor placed both knees on the sofa’s armrest in preparation to launch a dangerous object, the teacher packing up, preparing for a quick departure, Victor’s concentration like a hunter’s, the restrictions placed upon Victor now gone.

Freedom is wasted on bored adolescents.

Victor rose on his knees. The teacher zipped up his bag. Victor’s serial-killer tendencies were becoming excessive. The toy car flew out the window. Victor unleashed gasping guffawing.

The teacher got his money from Victor’s mother, explaining that he was in a hurry. The lift couldn’t come quickly enough. Victor and his mother were standing in the doorway, their arms around each other, waiting for the teacher to enter the lift, the mother’s brown eyes like a furry animal’s besides her son’s malevolent grin.

Be careful, the teacher thought, about what you hope for.

Outside, a man, holding his head, was telling his wife: “It came from that window there! It was that window there!”

The teacher’s stomach muscles quivered as he tried stopping his laughter, his mouth opening: there was silence; then the stomach muscles — contracting and expanding — forced out chortles, the bemused wife staring at the chortling teacher.

The teacher contacted Victor’s mother to announce that he was returning to England. It was a lie. He felt guilty about taking her money; she was so sweet and innocent that robbing her felt like a crime.

And he didn’t want to be around for Victor’s impending disaster.