A Matter of Time

Jane Deans | Péter János Novák

Published on 2013-01-15

Frith steps out into the grey, depressing familiarity of the patch she still thinks of as a garden at a time she knows is morning from her ancient alarm clock. She glances up into the hazy fog as she does each day, to assess the extent to which a semblance of light may be penetrating. This morning, within the billowing folds of damp cloud a sulphurous, bilious glow hovers like a searchlight beam, providing little in the way of illumination and no warmth, although Frith allows a small thread of encouragement to weave into the start of her day.

Along the cinder pathway fresh layers of fine dust display the prints of the girl’s boots as she moves towards a network of raised beds rising like ghostly islands in the gloom. She pauses by the first rectangular slab, a dark oblong mound constrained by timber planks, crumbling a little now from prolonged exposure to damp and housing what would have been a robust crop of potato plants. Frith adjusts the filter masking her nose and mouth before bending to inspect the nearest plant. A few dark, brittle leaves have struggled to the surface of the dusty heap of soil. She peers at them, unsurprised by their insidious coating and searches for any sign of a flower. They will need to be earthed up again, she decides, grimacing at the idea of the task; digging into the tainted earth will produce a storm of silver powder pluming up and coating all in its descent, including herself.

She walks to the apple tree, a spectral giant in the mist hung with fringes of dull spores and remembers her grandmother describing summer afternoons as a child lying in the shade of it with a book or clambering to the top to teeter on a spindly branch and marvel at the view across the sunlit valley. She shivers, conscious of the oppressive silence that hangs over the garden like the fog. On the tree’s lower branches one or two tiny, misshapen fruits cling in a valiant effort to perpetuate.

Beyond the tree, by the low stone wall that once marked the boundary with a neighbouring property there is a brave, rebellious clump of brambles making a stand against the suffocating effects of fungal invasion, producing fierce, protective thorns and exuberant, wet foliage tinged with hints of green amongst the smoky coating. Frith allows herself to hope for blackberries later on, in the time that used to be called autumn when there were seasons marking changes in climate; months when days were warm, hot even, and periods of fierce cold when the land lay dormant.

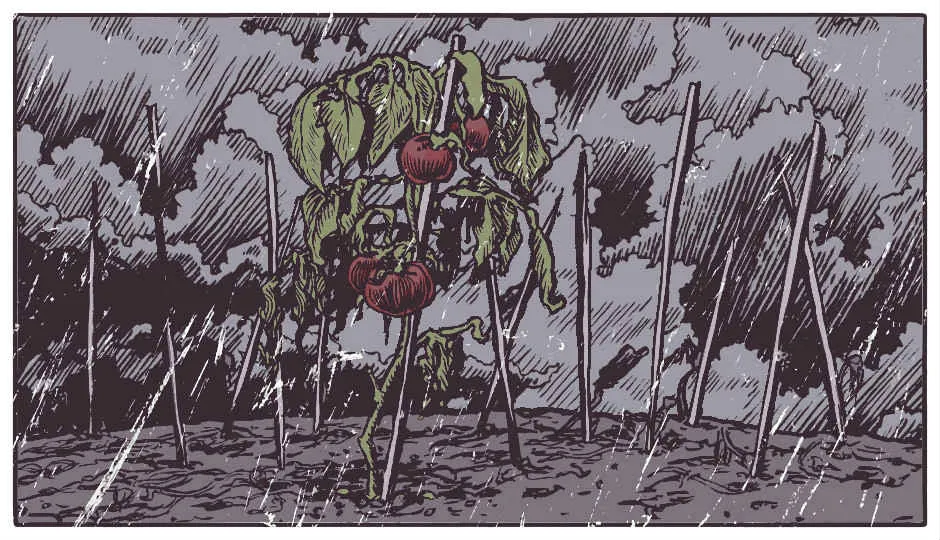

The greenhouse is barely visible at the end of the monochrome garden until Frith is near enough to touch its damp and slimy surface. She pulls the door open and steps inside. The tender plants here have not escaped the blight and she surveys the spindly pepper bushes, brittle stalks smothered in grey and moves slowly on towards the end of the small structure where she’s been nursing the tomato seedlings. She stops; holds her breath. There is a diminutive, amber globe attached to one of the plants, glowing like warm, evening sunlight. She bends to peer at its parent plant. There are two more ripening fruits clinging to the foliage, shining with impudent optimism. Frith stares then throws her head back, an almost hysterical laugh erupting from her lips and her eyes wet with tears.

The sound of footsteps crunching on the path causes her to turn and see the tall, bulky figure of Cal approaching; then he is there filling the doorway, his woolly hat jammed tight over his dreadlocks and long scarf wound around his face and neck.

“A brace of coneys,” he tells her. “Not much meat on them but they don’t look to be in too bad a state. We’ll get some broth out of them anyway.”

Her eyes, turned to him, are radiant. She shows him the tiny tomatoes illuminating their corner of the greenhouse. “Should we move the plant, do you think, Cal? We could take it inside the house. It might be special, have some immunity. And if we kept the seeds maybe they’d grow into stronger plants still!”

Cal reaches out to pull her to him, enclosing her in his arms, her cheek against the rough tweed of his overcoat. He looks over the top of her head towards the little plant with its defiant tomato warriors and thinks of the children he and Frith might have had. Her face, when it turns up to his, still damp from tears is itself reminiscent of a child’s.

“We’ll leave it be, love. If it is going to resist the blight it’ll do it here. Moving it will make no difference. Come back to the house now and help me skin the rabbits.”

He watches her later, staring at the flames flickering blue around the remnants of decaying logs in the fireplace and knows she is allowing herself to dream of a future.

“Frith love,” he murmurs. “Don’t get your hopes up. I know it was good to see, but not enough to signal any kind of recovery.”

She looks up, frowning, irritated; the extinction of possibility is hard to bear. He takes her hand. “We’ll keep watching it. It could be resistant. Only time will tell.” And he turns back to where the flames are ebbing in the fireplace, reducing the logs to glowing, flaky ash.