Reap the Whirlwind

Mateja Vidakovic | Sue Pownall

Published on 2012-12-21

My best friend in the world probably does not exist. We never speak longer than twenty minutes or so, and then I don’t see him for a year — but he is my closest friend. He has been so for my whole life. I hope he will be there when I die, or at least that I will meet him once more on that day.

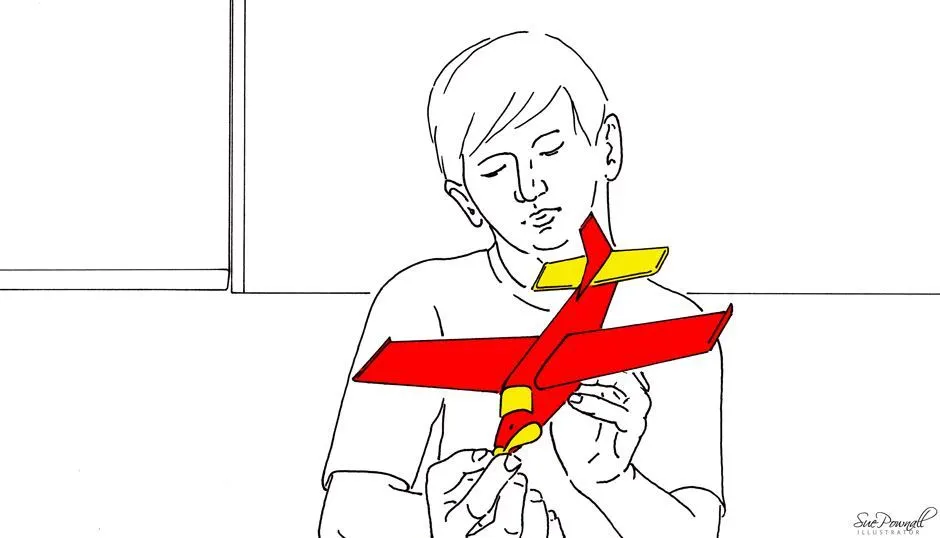

I remember the first time he walked up to our porch. I was playing with a plastic red and yellow toy plane, one of its wings infuriatingly skew. Trying to fix it took so much of my six-year-old attention, I barely noticed when the shabby, jean wearing kid stumbled over the two steps of our porch and in our view.

”You should run, tornado is coming,” I told him, barely taking my eyes off the plane. He looked dirty, like he ran through sweat and grime just to get to me and my toy.

”It’s ok,” he said, and sat next to me. He smiled disarmingly and, somehow compelled, I gave him the toy plane. He brushed his scruffy, sandy blonde hair from his eyes and attempted to bend the wing back.

“It won’t work, stupid,” I muttered emphatically. It didn’t. He shrugged, smiled again and put his hand on my shoulder in a gesture of farewell. I liked him, so I smiled back. He turned, and ran straight towards the field, towards the tornado. Like on cue, my mom ran out and dragged me to the shelter. I was still smiling.

He came again a couple more times. When I was ten I remember talking to him about masturbating, being relieved I was not the only kid in town doing it. When I was about twelve we made collages out of old comic books, and he told me Tamagochi toys were dumb.

He always looked like he traveled far and wide to get to my porch, to me. I never asked him where he came from, why he flung himself into a tornado or how he came back every time. It was something normal, something I grew up with. He has been doing it most of my life, with a casual trot and a clear eye.

My little toy airplane was replaced with comics, the talk of masturbation replaced by talk of girls. We were 14, still smiling, and he helped me decide which puppy to get.

”Don’t get any breed, get a dodger. They are healthier,” he said. I smiled and listened, and then we played some Gameboy. He lost his game, threw it to me, waved bye and ran to the tornado.

We were sixteen, and I was showing him the guitar I got for Christmas. He tried playing it, and told me I have to play him something when I see him next. That’s when I asked him what he does there. Where, he asked. There, I said, and pointed at the tornado.

“Reap the whirlwind, Todd.” He tapped my shoulder and left.

I never felt lonely without him, but it felt comforting to know he would always come back to say hi and do his strange run again.

He came a couple of times more, and then I did not see him again for a while. I moved to another town for my studies, and for a long stretch I pretended I was doing fine. In fact, I missed my friend. He listened, and always had a word of comfort. He was the only thing I could depend on to always be there, even if he said nothing.

I came back only to marry and buy a house next to my old family house. I pretended it was because of mom and her health, but in reality I needed my buddy to help me out through hard times. My wife never saw him. I loved her, but she wasn’t that kind of close to me.

He was there again when mom died. I cried but he didn’t. He gave me a solemn look, then asked me to play some guitar for him. I did that, still crying, as he whipped the dirt off his face with an old shirt he found on the chair. He gave me a hug and ran for the tornado.

He was there when I divorced, and when one of my daughters was hit by a truck my neighbor drove half asleep at 6 AM. He never cried but always seemed to know what to say.

I lost my job, but was applying for new ones. When I told him that, he giggled “What’s funny?” I wondered. “Nothing. You always fear what you have man. Losing it should be a relief.” I had no idea what that meant, but it sounded good to me.

“You heading out?” I asked him as he stood up to throw his empty beer can away.

“Yep. Be good,” he said, looking up. For a moment I saw him as a kid, sandy hair obscuring his view of my toy plane. Then he ran.

I walked back home that night with a full gut and a head full of pain and plans. I envied him. At least he always knew where he was going.