Fish

Paul Kavanagh | Daniele Murtas

Published on 2015-07-02

The boy knowing the river went for a small lure. I caked my big lure in some kind of smelly, heavy liquid that poured thickly out of a bottle. The bottle said the liquid smelt of fish. I thought the orange goo smelt of rubber. But what did I know, I was not a fish.

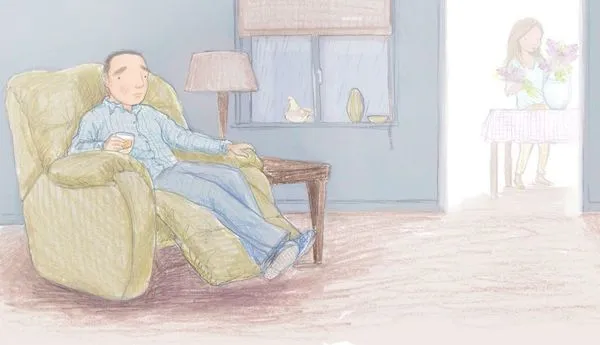

The boy really knew how to fish. He instructed me how to cast and how to jerk the line so that the lure in the water would resemble a real fish. A heron, I said, pointing. No, said the boy, shaking his head, disappointed. I was bothering him. It was a blue plastic bag lifted by a sudden breeze. Do you think we will catch any fish, asked the boy, suddenly showing his age, his vulnerability. I said yes and watched the water undulate as it carried the green scum to the sea. The river carried a lot of the green scum.

I oscillated between boredom and cursing the fleas and mosquitoes for not having the patience until I was dead. I spent more time slapping my legs and arms and the back of my neck than casting the big oily lure into the river. The fleas and mosquitoes left the boy alone. I think it’s too cold, I said. I had nothing else to say. The boy’s excitement waned just like the sunlight. I unhooked my lure and wiped my hands on my trousers.

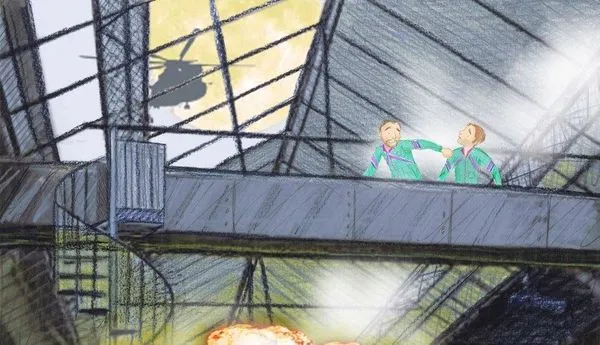

As in a great story, the boy got a bite. The rod showed that the bite was big. I sat down on the cold grass and watched the boy, excited and nervous, struggle. It’s a big one, I said. The boy didn’t respond. He looked very old and very wise and very independent. Slowly, he reeled in the big fish. I picked up the net and stood beside the boy and waited. I wanted to speak, to say things full of wisdom and wit, but I couldn’t think of anything. The boy was red in the face and blowing. Here it comes, I said sounding like good old Ahab. The boy was smiling, showing his even white teeth. You’ve got it, I said. I was so happy for him.

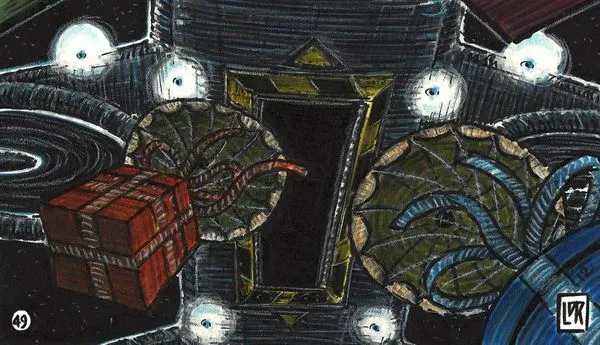

The river opened its mouth and released. The cat was not the weight. The weight was the rock attached with rope to the cat. The rope had been tied around the cat’s neck, but it had slipped and was now around the cat’s swollen belly. Both the cat and the rock had not been in the river long. The cat still looked like a cat, a wet black cat. The fish had not started to dismantle the cat. The rock still resembled a rock. The protrusions had not been rubbed away by the journey to the sea. Before the boy could comprehend his catch, I cut the line with my knife and tipped the cat and the rock back into the river.

What was it, asked the boy. A cat fish, I said.