Sentry

Erich Earl Forschler | Hannah Nolan

Published on 2014-04-30

Ray Rider sat at the large wooden desk in the center of the office and rubbed his face with both hands. He massaged his temples and then slid the fingertips over his eyes and applied pressure. Ray was still rubbing his eyes when Jeremiah knocked on the door twice and entered without waiting to be told to enter. He carried a large, dark leather planner book under one arm. Sounds of paper rustling and brief wisps of chatter followed Jeremiah in from the room outside. He shut the door behind him, muting the commotion just as a telephone outside began ringing.

“You okay?” Jeremiah asked.

“Ugh,” Ray groaned, taking his hands from his eyes and wiping the palms across the top of his neatly parted hair. “What the hell’d you do to me last night?”

“Me?” Jeremiah huffed, crossing the room and sitting on a leather couch along the back wall. “I didn’t do anything to you.” He put the planner on his lap and threw his arms out over the top edge of the couch.

“I gotta tell ya, I can’t take much more of that.”

“Well, it went a lot better than we hoped.” He took an arm down to flatten his tie and center it along the buttons. “I mean, really good.”

Ray closed his eyes and stretched as he nodded and said, “Mm-hmm.”

“You get coffee yet?”

“No — well yeah, I got some on the way in.”

“You need some more?”

Ray leaned forward and laid his forearms over the desk and looked at the paper coffee cup that rested there. “Nah,” he said after a pause, “think I’m good.”

“You need more.”

“No, no — if I drink too much I get a lil’…” he paused and bounced his shoulders while sticking out his tongue.

Jeremiah ignored him, instead shouting out for “Colleen!”

Ray winced and plugged his ears. “Dammit, man!” he scolded.

Within seconds a woman peeked into the room through a barely opened door, received the request for coffee and then disappeared.

“We raised almost half a million last night,” Jeremiah said, opening the planner on his lap. He looked up and smiled. “I don’t know about you, but half a mil is pretty good for a hangover.”

“Oh, shee-yut. I’m not hung over,” Ray scoffed, waving angrily.

“Right.”

The door opened again and Colleen walked in carrying a steaming mug. She laid the mug on the desk and said, “Here you go, Ray.”

“Thank you, sweetheart,” he replied with a smile.

She turned to leave, making eye contact with Jeremiah before she disappeared back into the sounds of fax machines and a male voice saying, “Hey, did you get the e-mail yet?”

Both men sat and watched the door for a moment after she left.

“Well, she looks good today,” Ray said.

Jeremiah looked down, smiled and said, “She does Pilates.”

“Huh.” Ray sipped the coffee from the mug and used his free hand to loosen his tie at the collar.

Jeremiah thumbed through papers in the planner, sighed and said, “So anyway, you’re speaking on the floor this afternoon with Anderson.”

“About his amendment?”

“Yes,” Jeremiah said. He looked up briefly and then stopped. “What are you doing?”

“Drinking coffee.”

“No. I mean the tie. Stop with the tie.”

Ray cocked his head back and arched an eyebrow while putting both hands out. “What’s the problem?”

“Stop getting undressed.”

“How bout you stop nagging — I just can’t breathe,” Ray replied, again working his collar.

“Ray.”

“What?”

“Garvey is coming here in,” he checked his watch, “about four minutes to meet with you.”

Ray moaned and sank back into his chair. “What the hell.”

“So stop undressing. Stop looking hung over.”

“What does that mean?”

Jeremiah shrugged. “I don’t know — sit up straight, for starters.” He took a sheet of paper from the planner and stood. “And read over the talking points for the Anderson amendment.” He stepped forward and placed the sheet on the desk. “And here’s your speech — so read that, too,” he added, taking another sheet from the planner and laying it atop the talking points.

Ray looked at the papers and mumbled to himself as he read before saying, “What the hell does Garvey want anyway?”

Jeremiah shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“Huh?”

“I don’t know, Ray — you made this appointment with him yourself.”

Ray slapped the papers on the desk and scowled at Jeremiah. “The hell I did,” he barked.

“Yeah, you did.”

“When?”

“Last night at the fundraiser.”

Ray rubbed his face. “Oh, Lord.”

Jeremiah laughed briefly and rapped his knuckles on the desk. “You’ve got about a minute or so now, so try to look alive when he comes in, okay?”

“Yeah, yeah,” Ray said with a wave.

“Can’t blow off the party chairman, Ray.”

Ray waved again. “All right, dammit! Leave me the hell alone for my one minute of peace.”

Jeremiah left him there and went out into the main office where staffers and aides sat behind desks covered with stacks of papers or books as they typed diligently or talked on the phone. One of them stood along the back wall with his sleeves rolled up, dancing circles around the fax machine and chomping obscenities into the air.

Garvey sat in a chair by the door leading to the hallway. Jeremiah waved at him and said, “He’s in there.” Garvey nodded and stood, buttoning his jacket and then smoothing it down with both hands before walking toward the office. “Just go on in,” Jeremiah added as the two men passed. Garvey thanked him and then disappeared into the office.

He heard Ray’s voice, thick with false exuberance, exclaim: “Hey, Donald! Great to see ya!” before the door closed off the conversation.

“Jeremiah,” Colleen called from the doorway where Garvey had just been sitting. She waved when he turned and saw her, motioning for him to come over. She stood at the door with one hand on the knob, talking to someone obscured from view in the hall.

“What is it?” he asked when he reached her.

“Hey,” she said, turning and pushing the door open more. “Mr. Roth here is asking to see Ray.”

Ernie Roth stood in the hall with his briefcase and wool jacket that was a half inch too long in the sleeves, his free hand adjusting the thick glasses which oozed down his nose constantly.

“Hey, Ernie,” Jeremiah said, offering a hand to shake. He stepped forward as Ernie Roth took his hand and shook it. Colleen ducked away and dissolved into the clamor of the office. “How’ve you been?”

Ernie shook his head and frowned. “Not good, Jerry — not good.”

“Okay?”

“We’ve got a problem.”

“All right?”

“I need to talk to Ray.” He looked around Jeremiah’s shoulder as he spoke.

“Ray’s indisposed. Why don’t you come to my office.”

Ernie frowned. His glasses began their ritual slide and his hand came up again to adjust them. “Who’s he with right now? Hofferman?”

“No.”

“Hofferman gets to go right in, doesn’t he?”

Jeremiah shook his head and stepped back. “He’s not with Hofferman, Ernie.”

“Well, that son-of-a-bitch gets to go right in, and I get told to stand in the hallway.”

“Just come to my office, will you?” Jeremiah said as he turned and made for the door opposite Ray’s office. Ernie Roth sighed, adjusted his glasses and then followed Jeremiah’s path between desks and staffers, glancing back at Ray’s door at least once as he went.

Jeremiah dropped the leather planner on his desk, turned his back to it and hiked a leg up on the edge and settled in with folded arms. Ernie shuffled in and closed the door behind him. Before Ernie reached the brown leather chair facing the desk Jeremiah said, “Look, Ernie. You know how it works, so don’t come down here demanding a meeting when you know — and I know you know this — when you know that you have to go through me first.”

“Oh?” Ernie mused. He hummed to himself as he lowered his bottom into the chair with a groan.

“Now what’s the problem?”

“Oh, I think you know.”

“Maybe I do, maybe I don’t.”

Ernie crossed one leg over the other and clasped his hands together in his lap. They watched each other for a moment. “Okay,” Ernie said suddenly, “You have to change the language in that Anderson amendment or else get Ray to vote against it.”

Jeremiah scoffed. “It’s going to pass with or without Ray’s vote.”

“Uh, yeah. Partly because Ray went to bat for this, big time.”

“Well, it came out of committee like that, and you know Ray isn’t on—”

“But we had an understanding.”

“We didn’t have shit,” Jeremiah said flatly. The words held the space between them, stretching out an empty and awkward silence.

Ernie sighed and looked away, surveying the book shelf along one wall, filled with plastic binders of differing sizes but similar colors. “It’s getting to be about my job now, Jerry.”

Jeremiah took a deep breath and held it, shaking his head.

“I hear things back at my firm — whispers that stop just when I enter the room, or ones that start as soon as I leave, you know?” Ernie pushed the glasses up and looked at Jeremiah. “People are losing faith in me, Jerry. Maybe it’s because I’m old. Maybe it’s because I’m just not good at this anymore.”

“Look,” Jeremiah began to say, but Ernie went on:

“My biggest client right now is going to lose out if that amendment becomes law, and here I was thinking we understood each other, but then I talked to Walter yesterday — you know Walter.”

Jeremiah nodded. Ernie continued. “Walter’s a policy nut, and his little policy nut brain says there’s something wrong with the language in there — there’s an exemption for the unions but not my client. And ‘it’s hidden,’ he says. Real subtle. Almost like it has your personal touch.”

“Well, that’s funny considering I had nothing to do with writing it,” Jeremiah replied. He fought off a scowl as best he could.

“And then I see that son-of-a-bitch Hofferman gets a meeting whenever he wants one—”

“Ray’s always been pro-union,” Jeremiah interrupted, adjusting his perch on the desk and looking down briefly. “He ran on it the first time around. It’s always been that way.”

“So what? That means they get an open door policy but I don’t?”

“No, it’s not an open door policy. Everything comes through me — you know that.”

Ernie’s eyes narrowed behind the glasses as he pushed them up. “We’ve been doing this for almost eleven years, Jerry — you and me.”

“Yeah.”

“I know you revel in the self-righteous idea that you’re the gatekeeper here, but…” Ernie paused and let his gaze fall to the floor.

“But what?”

He looked back up, his eyes focused and lips tight, saying, “But we had an understanding.”

“So you keep telling me.”

“Well, change the language.”

Jeremiah shook his head. “We can’t do that now. It’s too late. Ray’s thrown in with Anderson, it’s got the votes to pass by a large margin, and Ray can’t afford to—”

“Don’t give me this election year garbage,” Ernie interrupted. “I’m not the press. You know me. I know you. We know this city — we know this game. But this is my job we’re talking about now.”

“Come on, Ernie — you see the same polls we see.”

Ernie waved one hand in the air and used the other to adjust his sliding glasses. “And don’t tell me about shifting demographics, Jerry!” he exclaimed. “We had an understanding here!”

“Just calm down,” Jeremiah said, unfolding his arms and patting the air with his hands.

“Well, what about that tax rate reform?”

“What about it? It has nothing to do with this bill.”

“Yeah, but last time I talked to Ray he gave me the whole, ‘Oh, I’ll definitely get on board’ blabber, and now there’s just nothing. I mean nothing. And because why? The polls? Jesus Christ, Jerry, I thought Ray wanted to stand out.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s just blowing in the wind now, and there you are too. You’re protecting him, but I lose out here, you know.”

Jeremiah folded his arms and sighed. “Well, from where I sit I’m protecting a lot of people.”

Ernie laughed, adjusted his glasses again and pulled himself up from the chair.

“What’s so funny?” Jeremiah asked.

“Oh, just you and your high horse.”

“High horse? Ernie, if you go in and talk to Ray right now, when both of you are pissed off about whatever, it’s just going to end badly. Ray will burn that bridge in a heartbeat. He’s done it before. You want to talk about losing out, go in there and piss him off to the point of no return and see what happens.”

“You know what will happen,” Ernie said, bending down to lift the briefcase off the floor. “We’ll pour resources into—”

“You can try,” Jeremiah said with a laugh. “Ray’s approval is incredibly high with the voters, and Ray’s squeaky clean. Cleanest one I ever worked for. Shit, it’s worth protecting. I protect him from political harm, and he keeps his image, which protects his constituents — hell, it protects the whole damned system that way.”

Ernie wore a sly grin as he slowly shook his head. “Like I said: high horse.”

“High horse my ass. This is reality. I’m protecting you, too,” Jeremiah said, unfolding an arm to point a finger at Ernie.

Ernie laughed. “In what way?”

“By mitigating the harm your rash reactionism does to your political relationships.”

Ernie scoffed and turned, facing the door.

“Let this blow over. It’s not like the amendment actually hurts you — it just doesn’t exempt your clients from the new regulations. And as soon as the election’s over with we’ll get to work on that tax rate stuff, I promise.”

Ernie nodded and took a step toward the door. He paused and nodded again before turning to Jeremiah and asking, “So how’s Jill these days?”

Jeremiah opened his mouth to speak but paused momentarily and shook his head slightly. “She — uh, she’s fine,” he said. Then he asked, “So are we done talking business now, or…what?”

“In a way.”

They stood in silence for a moment, with Jeremiah sitting on his desk and Ernie staring at the door.

Jeremiah cleared his throat and said, “Well, do we have an understanding?”

“Oh, of course,” Ernie said, turning to make eye contact. “I understand that everything goes through you. I understand that Ray’s untouchable — squeaky clean! A man of the people, and all that.”

Jeremiah nodded. “Well, good then, I’ll—”

“And you should understand that if that amendment doesn’t change, Jill’s going to hear a little song from a little bird about loyalty.” Then Ernie smiled on his way out the door.

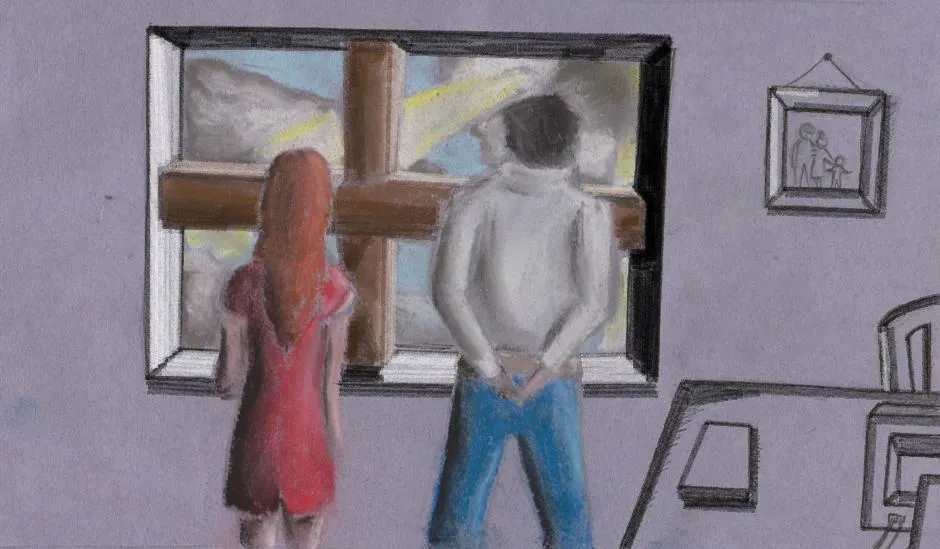

Jeremiah sat on the desk and stared at the floor, hearing the chatter and ringing phones that bled through the wall but not listening to any of it. After a few minutes he stood and walked around his desk to the window. The morning sun was still early in its climb, showering the concrete landscape in warm, golden hues. Tufts of cloud drifted by the bright, empty blue backdrop.

He was still watching the sky when Colleen came in the office and quietly shut the door behind her. “Hey,” she said, almost afraid to disturb him.

Jeremiah turned and forced a smile. “Hey.” Then he looked outside again. She came to his side and waited a few feet away for a moment before stepping closer and putting a hand on his back.

“Is something wrong?” she asked.

He took a deep breath and shook his head as he stuffed his hands in his pants pockets. “Oh, just…” he let the words fade without finishing. The clouds marched on outside. Jeremiah stood and watched them go. She stood and watched him watch. And inside one pocket, the thumb of his left hand spun the ring around the finger.