Making the Eyes

Jeroen van Honk | Hannah Nolan

Published on 2016-01-08

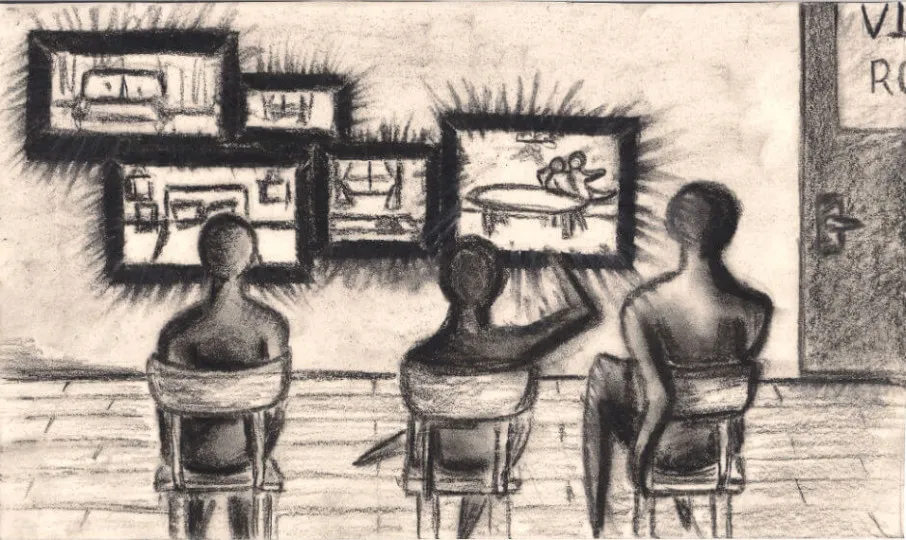

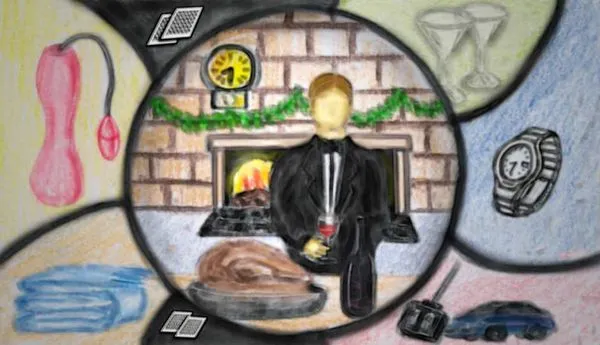

It was dinner time and as usual they were all focused on that one monitor, about halfway up, on the left.

“Here he comes,” Paul said.

“Ah, yes! And there’s the daughter,” Kenny confirmed.

They were all rather satisfied looking at the screen. They knew what was going to happen, but everyday again they were religiously pleased with the results.

Their job was “to keep an eye out,” as Paul himself described it to people when queried. It seemed like an easy enough job at the time. He still remembered the job interview. It was a very curious one. He was sat down in front of three people, on a small black folding chair. They stared at him in silence for a long time. Then, the middle man, sweating profusely, his eyebrows glistening, announced that he was hired.

Kenny nudged Paul in anticipation. The daughter on the screen had stopped eating, her plate still half filled. The mother held up three fingers. Three more bites. It was always the same, unless they had pizza, and they only had pizza on Sunday. Today, they had potatoes and cabbage, and some red meat.

Kenny started to reminisce about how they first “found” this family. He often did. “Do you recall,” he said, looking left and right to his colleagues. Paul and Tom nodded sagely.

“We were all flustered,” Tom added.

“The way he walks, the way he tousles the daughter’s hair,” Paul continued.

“I remember how I could not take my eyes off the screen,” said Kenny. “I simply asked you guys: ‘Name?’”

“And you were so happy he was called Ronald.” Tom again.

“We all were,” Paul concluded.

“A fine name.”

It had been surprisingly easy to get over the moral objections of observing a bunch of people all day long. It had been easy because these people were so unremarkable. When they discussed the privacy issue in the press it always sounded as if intrigue and scandal were everywhere. It made you curious. But one day in this control room would take the glamour off for everyone. It would be a useful day out for primary schools. The kids could cross it off their list of careers.

The daughter on the screen had made it through the dinner trial. She had done so with some theatrics, as usual. These were scripted theatrics, completely accepted by the rest of the family. It was part of their ritual, just like observing them was part of Paul, Kenny and Tom’s. Now the daughter would go upstairs and brush her teeth, and the parents would lean over the table and kiss, a couth kiss on the lips. Ronald would take care of the dishes and read his newspaper. He would settle in his favorite chair with an expression of complete satisfaction.

“Beautiful!” expounded Kenny. It was their favorite moment of all. They had discussed cutting it out and putting it on instant replay on one of the screens, but they did not want to risk ruining the magic.

The thing was that once the moral scruples about the job disappeared, something unexpected happened. This uneventfulness, the boring repetitions and patterns, became a laudable trait. It is what they scanned the screens for. Not for suspicious behavior or clandestine facial expressions, but for a perfectly ritualistic life. Ronald’s family was the only one they had found so far. The others were all ungraceful in some way; stumbling on the stairs here, cutting themselves chopping vegetables there. Paul, Kenny and Tom, and pretty much everyone else at that, all came into this control room with hours and hours of Hollywood footage running through their heads. In Hollywood, nobody cuts his finger chopping vegetables and nobody stumbles on the stairs, unless they are supposed to cut up their finger, supposed to stumble. Things are coaxed into perfection in Hollywood. Things are blunted into asymmetry in the rest of the world.

Paul came home at about ten. His wife was sleeping on the couch. He imagined, as always, him, his wife and the offspring they did not have, sitting at the dinner table, perfectly on time. Always when he did, he would see himself turn his head from his plate, from his wife, from his daughter, in order to look straight at the lens. He could never again be blissfully unaware of the spectators. At these moments, inadvertently, he vouched to become an actor, to win the right to get it right in five takes instead of one.

His wife awoke at the sound of his footsteps. She smiled, a little flummoxed but sweetly.

“How was your day,” she asked.

“Fine, honey,” he replied. “How was yours?”

“I’m pregnant,” she said, not giving the words the weight they deserve.

Paul felt something flutter inside, almost as if he were the one pregnant, and the baby was kicking. “Really?” he said. He knelt down next to the couch and grabbed hold of her tightly. He realized everything’s okay. He realized they nailed that scene. His work buddies would have been impressed.

“It’ll be a daughter,” Paul whispered to her, stroking her forehead.

She smiled. “How do you reckon?”

“Trust me,” he smiled, “I know.”