An Act of Love

Published on 2014-03-12

After the worst day of his life, Khaled abu-Baher went to the sea to seek comfort. The past year had been a large illusion, like an escalator taking him higher and higher only to drop him from the clouds to the bottom of the sea.

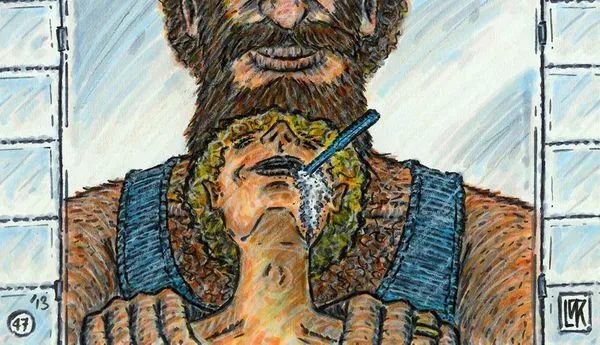

The abu-Baher family was as much connected to the Jaffa as the seashore. There Khaled’s father had taught him to fish, and his grandfather had taught his father, and like this, or so the abu-Bahers claimed, it went as far back as the Phoenicians. Khaled never finished high school, but he was a well-educated man in his fields of fishing and seashore-manship. The sun had made his skin almost purple, which made his light blue eyes more jarring, like tiny shards of blue tinted glass embedded in rough reddish clay. He had a long face that was very hard-lined, like a typographical map of Africa, with bumps and deep river-like concaves that wrapped around his eyes and mouth. A scar from the jagged fins of a fish left a Nile-shaped scar running down his left cheek. Woman found his rugged face handsome. Yet he was too shy to approach the fairer sex, as most men whose social lives are comprised of floundering fish breathing their very last breaths.

At the age of thirty Khaled’s father found him a match. Lyla was a small, giddy woman, only a few years out of high school. She was either making jokes or cracking up to them, and she laughed so freely that she sounded like a braying donkey. This bright free laugh was contrasted with her affinity for black and purple: she was always dressed in black from head to toe, usually with black jeans and a loose fitting blouse that reached well below her waist, and purple wristbands on each arm, purple tennis shoes and purple hijab.

Khaled preferred not to go to the mosque to pray, even on Fridays. Instead he brought his green prayer rug with a dulled image of the Dome of the Rock with him to the sea. He prayed in the same spot among the rocks where he sat and fished. This was a cleft, a hideout, where like a dove, Khaled spent his day squatting, listening, waiting for a tug on his line. He hadn’t many friends. Sometimes Rashid, who had been his neighbor growing up, would come by and they would smoke a Nargilah together and play backgammon.

When Lyla’s father offered Khaled a job in his restaurant as a fish chief, he accepted. Though he was sad to leave the sea, feeling almost as if he had betrayed it, he happily went to work where he could watch Lyla wait tables, her bray-like laugh filling the noisy dinning area.

During his engagement he was happier than he had ever been, living purely off the sweetness of anticipation for life with his wife to-be. His head filled with dreams.

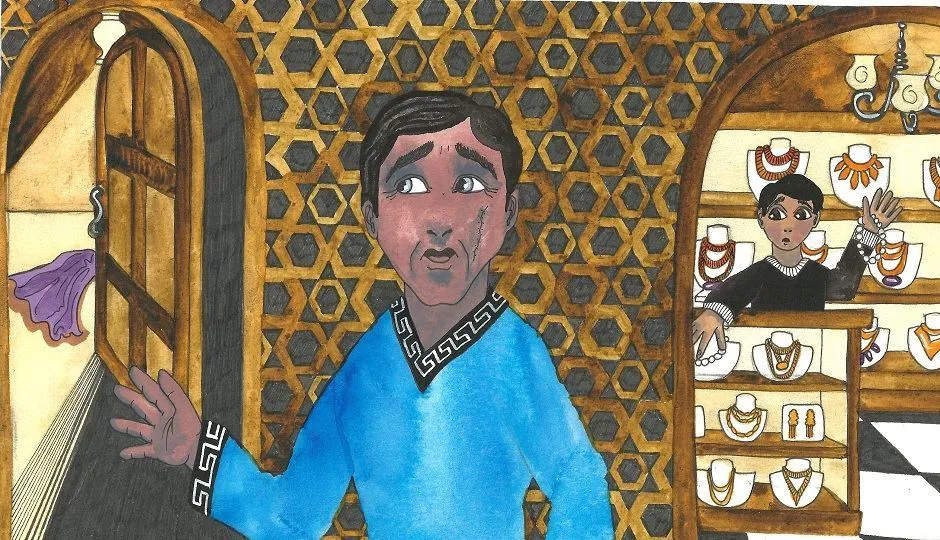

On this day, the worst of his life, Khaled went to the jewelry store where Rashid usually worked. The fisherman had taken with him most of his savings in a bare white envelope. He had felt that Lyla had been very distant as of late and wanted to buy her a lavishing gift—one that would say she was his.

Khaled opened the jewelry store’s heavy glass door, causing a small bell to ring, and was greeted by Rashid’s 14-year-old brother. The boy’s face was pale and he was avoiding Khaled’s piercing blue eyes. At every piece of jewelry Khaled looked at, Rashid’s younger brother begged him to buy it, offering him 10 or even 20 percent discounts.

Khaled eventually asked to see a pair of zucchini shaped earrings made of purple tanzanite. “Great choice,” said the young boy, quickly wrapping the black velvet box in red wrapping paper. The boy shoved the expensive earrings into Khaled’s hands. “Don’t worry, Allah will Provide,” said the boy. But as Khaled was thumbing through the bills in the envelope that held his savings, he thought, ‘No! no! We will need this money very soon if we are to have our own place. And what about a child? Diapers and food are expensive.’ He told the boy he was sorry and headed for the door.

Khaled got as far as opening the heavy door and making the bell ring, before he paused. ‘I must get her something, however small. Just a small symbol for her to wear so she remembers she is mine.’

As he turned around he heard his own death knell: that singular bray-like laugh of Lyla, which came from the back office. He ran passed Rashid’s younger brother and began opening the wooden office door. He didn’t need to open it all the way. Just far enough to see Lyla’s purple hijab sprawled on the grey carpet floor.

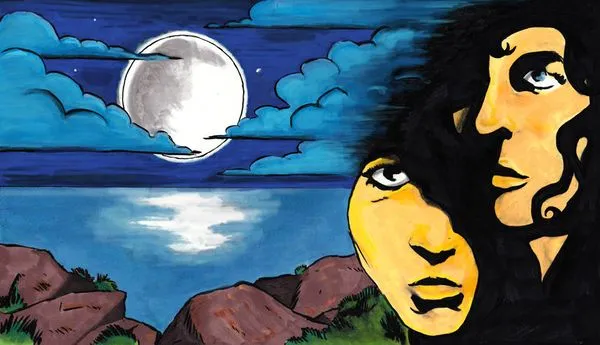

It was a late summer evening and the sun had started her orange descent. The weather was unusually temperate and the clouds were swirling in the sky. The waves that crashed onto the shore were unusually large, and the sound of their rhythmic pounding echoed over and over through Khaled’s ears. The beach wasn’t empty, yet he felt entirely alone within his rock cleft. As he watched the great waves crumble, he began to make a connection between the storm that raged somewhere far out over the sea, and the storm within his own heart. He felt the only love he would ever have would be for the sea and the sea would love him back.

The next day, Khaled’s body was found strewn upon Jaffa’s rocks. The few that knew him considered it suicide. No one suspected that it was an act of love by the sea.