A Cry For Attention

Debbie Lechtman | Jordan Wester

Published on 2013-08-03

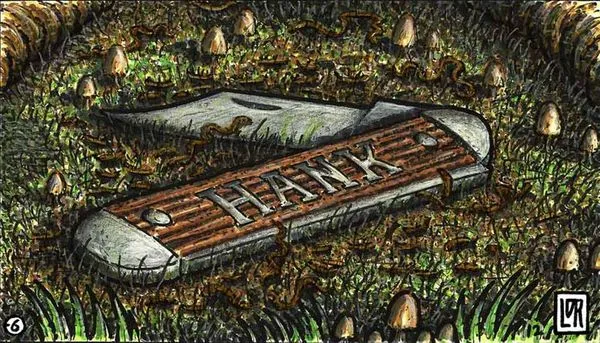

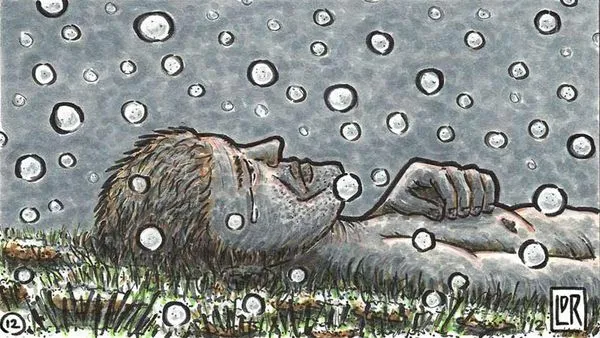

When Sibley died, they said it was a cry for attention.

I hear them say it, and in my head, I mock them, because I know that they are so right and so wrong. So right and so wrong — it’s a peculiar inconsistency. But it’s there, and it’s true. They are so right and so wrong that my head spins.

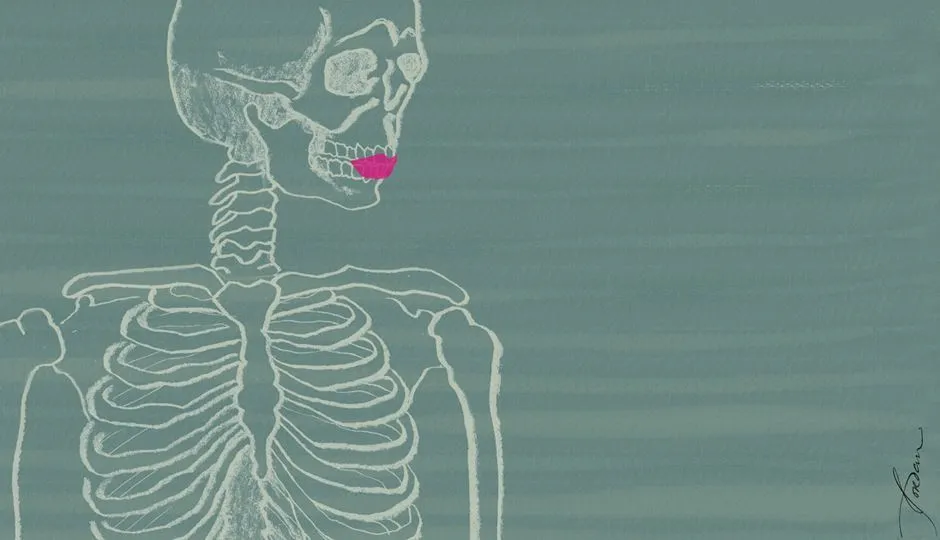

With blank eyes, I stare at the black casket. It’s shiny. It glistens; I can nearly trace the jagged lines of my face in its reflection. The jutting bones, and the grotesque angles. I can count the pattern of my ribs. Although I know that I shouldn’t, I huff with a secret satisfaction.

I like that I can count the pattern of my ribs. I love it.

And then my heart flutters, and after that it beats a little harder — thump, thump, thump — and I know that I deserve this, I deserve this anxiety, this relentless tachycardia. I deserve it because Sibley has died, and I feel no pain.

I am incapable of feeling pain, I suppose. I am numb.

I feel no pain, even though I know that it’s all my fault.

I feel no pain, and I understand that these gossipy ladies in the back pews, these gossipy ladies in their extravagant hats and long white gloves, I know that they are right. It is a cry for attention, and I am crying louder and softer than anyone else in the world.

I became anorexic first. Why do I get to die second?

I bow my head and place it between my knees, and I whimper. I hiccup. Finally, I am sobbing.

But here’s my secret: it’s not for Sibley that I cry. It is for me.

I am a selfish piece of shit, and I know it.

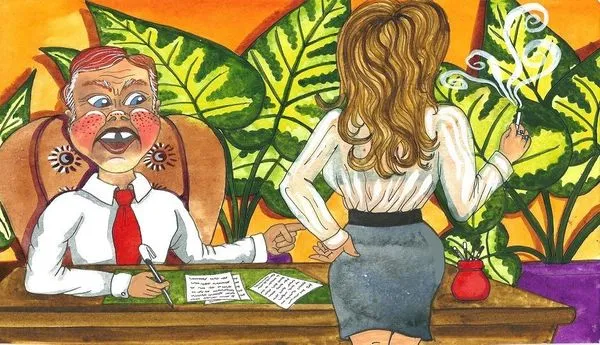

The priest speaks. Some nice words about Sibley, some this and that, but I am not listening. I don’t hear the words.

My twin sister has just died, and yet all I can think of is the extra layer of flab on my stomach. There shouldn’t be any flab on my stomach! I berate myself, and my temples pound: boom, boom, boom. Concave! Concave! My stomach must be concave, the perfect inward curve.

I try to fool myself: Sibley would’ve wanted it, I say. Sibley would’ve wanted me to finish what we both started, together as sisters. She never did get to be weightless, not even in her death. And that was her goal.

That was our goal.

Wasn’t it?

It wasn’t a cry for attention, no. It was our goddamned goal.

Two twins, light as a feather. Two twins, subsisting on the drug of starvation and air. Two twins, perfect, perfect, perfect. Two twigs.

But now Sibley is dead, and she is not weightless, not yet. Maybe when her soul departs her body — maybe then she will be.

Between my legs, my lips contort into a smirk. A-ha! I am certain that this is it, this is when I finally beat my twin sister. This is when I finally taste the sweetness of victory. Sibley beat me in death. And she beat me in life, mostly. But I will beat her at this — I will be weightless in life, I will be oxygen and air, and this time, she will come in second. She will never be weightless in this world, because she’s already left us for the next. And I will! I will! I will!

In my head, I perform a series of calculations. Some quick arithmetic. It’s not complicated, no, but it’s precise. It must be precise. Calories, grams of fat, carbs. If I’m not precise, I’ll be devastated, and I know it.

I hear shuffling and mumbling and tearful condolences. It’s a blur, as if I’ve pressed the fast-forward button, as if I’m trying to skip this scene. I’m not particularly interested in it, anyway. The service is over. Soon, Sibley will rest underground.

I am already thinking of the next diet.

The gossipy ladies in the row behind me stare at me with sad eyes.