Pamphliterature

Caroline Kepnes | Lakshmy Mathur

Published on 2014-02-18

Sue Manor always wore tan pants, the kind you get at Ocean State Job Lot if you never want to have sex again, pants you buy instead of committing suicide, slacks designed for a large, depressed segment of the population. Sue never crossed her legs and kept her feet planted on the ground. Her moisturized ankles emerged swollen from tube socks crushed into cardboard by hot cycles in the wash.

“Are you listening to me, Eric?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then, about aromatherapy,” she continued.

Sue made you want to be dead and maybe that’s why she was a grief counselor. She had a perm. She had a never-ending supply of floral rayon tops that revealed nothing about her tits. It was impossible to know if she was a 32A or a 36C. It was possible to imagisne that nobody would ever know besides Sue. Eric could picture her dead, a corpse in a tan bra and tan pants. It was easy to imagine her harvesting rancid vegetables at a salad bar in a grocery store, not a Whole Foods, a Stop & Shop. She drove a blue car. She was invisible.

“Do you feel depressed today?”

“No.”

“Are you sure, Eric?”

Sue was a grief counselor, in all likelihood, because her entire life was an exercise in grief. She probably saw matinees alone, at night. Musak flowed through her blood and into her heart rendering it incapable of beating all that quickly or all that slowly. As a child, she probably feasted on day-old corn muffins, split down the middle by a plastic knife. Buttered.

“Are you thinking of going back to work soon?”

“Sue, what was your first job?”

“I scooped ice cream,” she beamed. “Started when I was fourteen, stopped when I was eighteen, old enough to work in a diner and make tips.”

And it made sense, Sue Manor: always a servant, never served, never a bridesmaid, never a bride.

“You look like you have something to say, Eric.”

“How come you get to live and my dad doesn’t?”

She looked down at her thighs in those tan pants.

“I’m sorry,” he said and he was. “That was an asshole thing to say.”

“That’s a perfectly normal thought.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Try and go forward, Eric. Someday you’ll have a baby and you’ll see him in your child.”

“I’m not even married.”

“Not right now, but time heals.”

“Right. And depressed thirty-six year old men are always falling in love and getting married,” he growled. “What a great idea. Have a kid right after losing my dad. Hey, it’s not like I have any issues to pass on to my unborn child or my imaginary cunt wife, because she’d probably be a cunt. Only a cunt would want someone this fucking depressed.”

Sue was unperturbed. “I know it’s a sensitive subject.”

“I don’t want a baby.”

“I brought some literature.”

“No, you didn’t bring literature. You brought paragraphs of generic bullshit about life and death. It’s not Tolstoy. It’s some psychology grad student making an extra buck and some drug company trying to get paid.”

“Okay then,” she said and he hated himself as she left, pamphlets in hand.

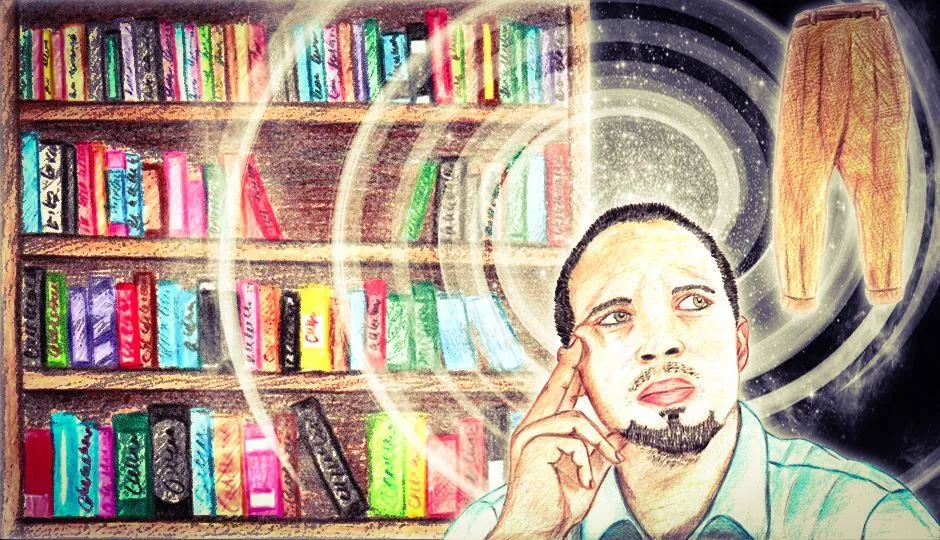

The next day when Eric walked down the driveway to get the mail, he found Sue’s pamphlets in the box. One leapt out at him. It was called _Are You Depressed? _There was a cartoon of a sad black woman on the cover in tan pants like Sue’s. Eric read it closely as if it were literature, as if it would be devoured indefinitely, checked out of the library, assigned in school, immortalized. He shelved it with his ravaged novels. It was the smallest book, so small that you wouldn’t know it was there unless you knew it was there.

When Sue Manor died, Eric went to her funeral. She looked beautiful in the casket in a long dress with roses. She was a 34 C, he would guess, and she had on lots of makeup and her eyes were closed and he couldn’t help but think that she’d put on the dress and the lipstick a little too late. She obviously didn’t read her own literature or she would have known that you fight depression by treating your body like a temple.

Eric was equally surprised by the turnout at her funeral. There were at least a hundred people. Sue had a son who sobbed. There were coworkers, former clients who raved about her compassion, a relatively glamorous sister who seemed determined to get through the day as quickly as possible. He ate sugar cookies in the church basement and stood around listening to people talk about upbeat Sue Manor. She played bridge and she volunteered at the hospital and she loved reading, particularly Nora Roberts books, but also the hard stuff, “you know, book-books like they make you read in school” said a woman. And Sue had a boyfriend in tan nylon slacks. He sat in a folding chair refusing sugar cookies, cranberry juice and affection. Eric overheard him tell someone that he was a maintenance man at Sue’s building. “Won’t be the same without her,” he said.

Eric waited a couple of weeks before going to Sue’s old building and staging a run-in with her maintenance man beau. He pretended that he was lost and the two men got to talking. Sue’s boyfriend had a name—Don Mooney—and Don liked to have a beer at a dive around the corner every now and again. He didn’t remember Eric from the funeral, which was lucky.

Eric and Don sat at the bar watching the news. They played Keno. They lost. They watched the Patriots, who also lost. According to the literature in Eric’s bookshelf, sometimes, the best thing to say to someone in mourning is nothing. In a better world, one of them would have hit some numbers on Keno and Tom Brady would throw to someone worthy of his arm and Sue’s pamphlets would be canonized, read by all.