Finley’s Airplane

Published on 2013-01-18

Finley should’ve been happier — he should’ve been beaming out there on the hardwood. At seventeen he had a car, a job, and a girlfriend. Life for him was good, and about to get better for his imminent release from a societal obligation that had all the inconvenience of a full-time job, but with none of the benefit.

He had adult problems, problems I wished I’d had. Graduation meant he’d finally be able to attack them undistracted by books, hard chairs, pointless schedules, ringing bells, and testosterone-addled jocks. He ‘d be done with compulsory failure, free to capitalize on his advanced placement in the real world.

Maybe he was just having a shitty day.

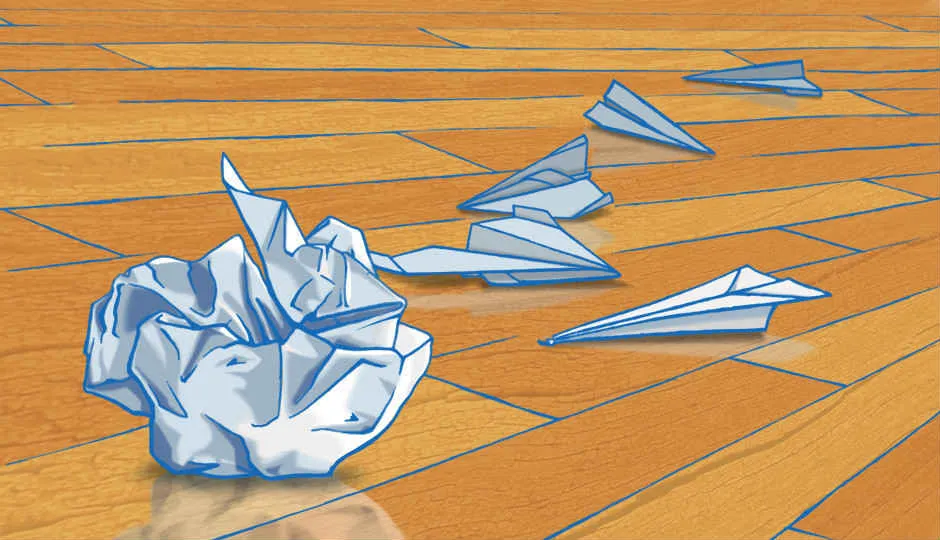

Finley fidgeted while he waited for Bowes, who was kneeling on the court next to a downed paper airplane. Finally Bowes called out, “Eleven and five eight — wait!” He squinted at the measuring tape he held to the plane’s nose. “Nine sixteenths!”

Babisch, the contestant who had constructed and thrown the plane now lying at Bowes’ knees, dropped his jaw. Palms spread, he mock-implored, “Jesus! A sixteenth of an inch?”

Bowes clicked the tape release. The tape skittered across the hardwood then punctuated the death of Babisch’s appeal with a crack.

Our teacher and event organizer, Mrs. Warburton, smiled with low-powered benevolence as she recorded the eleven and nine-sixteenths on her clipboard. “Good effort, Mr. Babisch. However I am sorry I am going to have to disqualify you for failing to land between the lines.”

From the bleachers came a taunt in the voice of Mickle: “Better luck next year, Babisch!”

Babisch lumbered toward the bleachers, swatting as if at a fly.

Now Finley toed the line, a strip of masking tape applied to the gymnasium floor. Ahead of him stretched a long, rectangular runway bounded by more tape, open at the far end and empty except for three inverted Styrofoam cups. Each cup bore a name in Sharpie.

The cup nearest Finley was ‘BOWES,’ in big, blocky capitals that leaned precariously upon one another as though collapsing under their own weight. The real Bowes knelt as close to his cup as permitted by the runway boundary.

He was speaking to it.

Further out, another cup elegantly and precisely announced itself: “Mickle.”

Furthest away, well beyond Mickle, was “Muller,” prettily scripted, embellished with color and shadow, accessorized with shooting stars, rainbows, and maybe a unicorn or two. The human Muller sat chatting, radiating a pretty and smart Girl Next Door allure that could’ve won her the female lead in a John Hughes film.

Finley glowered at the cups, the runway, and the many goals surrounding him in the gym. He fingered the flat sheet of paper in his hands.

Next to Finley stood Mrs. Warburton holding the clipboard to her chest. She turned her benevolence now to him.

“Mr. Finley, does your — plane — have a name?”

Somehow Finley soured his expression even more. He shook his head. He retreated from the line.

My final hour as a student of physics had begun with me on a bleacher in the school gym. Finley arrived just ahead of the bell, disheveled and with freshly wounded knuckles.

I asked him as he approached, “What happened to you, man?”

“Woke up late at my girlfriend’s. I shoulda been up at 4, but didn’t til like, 6 or something. Missed the first couple hours.”

“Whoa. She live far away?”

“Yeah, she teaches in a whole different district — Lapeer.”

“Lapeer? Shit man, that’s far.”

“Yeah, but we figure it’s better like that, ‘cause if she taught here, that’d be weird. That and my car broke down.” He flexed his fingers. “Fixed it, though.”

The bell rang. Bowes distributed sheets of typing paper to the class. We set to constructing airplanes with varying proficiency — Bowes folded his with the economy of motion that comes from much practice. On finishing, he emblazoned every broad surface of his plane with the word, “Destiny.”

Finley folded his arms after laying the paper next to him on the bleacher.

I fashioned the first paper airplane I had in maybe ten years, praying for something less than a miracle: Just don’t let me make a fool of myself. On finishing it, I held it up for Finley to appraise. He took it, saying, “Look at that, man. If you did this,” he penciled eyes, ears, whiskers, and a nose on the plane’s forward fuselage, “it looks like a mouse.”

“I can always count on you for validation,” I said, drily.

Then we were silent. I wondered whether Finley also felt the camaraderie that bonds the living representatives of a specie near to extinction.

Mrs. Warburton sought a volunteer to go first. Only Bowes stood. At the line, he launched his Destiny with a hard push. It floated, rather than flew, to a point a respectable distance from him on the runway.

“I’ll measure it!” he volunteered, then he did. From his knees he announced, “Six foot eleven.”

Following Bowes came a procession of disastrously impractical craft, all crashing at the end of ever-so-brief careers that one could call, “flight” only if afflicted with a preposterous generosity. Mrs. Warburton disqualified most for landing outside the runway perimeter. A few bested BOWES, however. Over time, it’s position ratcheted down from first to third.

At a pause in the competition for lack of volunteers, Finley punched me. “Go, man.”

At the line I thought I saw just a little more curl at the corners of Mrs. Warburton’s smile than I had seen from the bleachers.

“Mr. Kidd, does your plane have a name?”

I glanced at the plane in my hand. “No.”

From the bleachers, Finley shouted, “Mighty Mouse!”

I shrugged at Mrs. Warburton. “I guess I’m calling it, ‘Mighty Mouse.’”

“Very well, then: Mighty Mouse. Please proceed.”

On my release, Mighty Mouse corkscrewed to a point more or less behind me.

Bowes came over to my side. He placed his toe next to Mighty Mouse, looked to the line, and queried Mrs. Warburton. “That’d be negative, wouldn’t it?”

“Let’s just call it, ‘zero,’ Mr. Bowes.”

“Oh, who gives a shit,” I sputtered, snatching up Mighty Mouse and crumpling it into a ball.

Finley shook his head. He turned. He retreated — seven steps.

“I wanna call it, ‘Margaret.’” He crumpled the sheet into a compact ball, charged to the line, planted a toe. He hucked “Margaret” along a trajectory that spat on Newton’s grave, over BOWES, over Mickle, over Muller. Margaret seemed fit to fly forever until she struck the gym wall beyond the open end of the runway. She crashed to the floor.

Bowes leapt, punching the air. “No way!”

Mickle laughed, laid down his cards, applauded. He encouraged Babisch to do the same.

Muller obtained the details of the controversy from her companion, then the two of them went back to chatting with unperturbed grace about nothing having to do with the competition now in crisis before them.

I received Finley like a cornerman congratulating the underdog that had just kayoed the champ.

Bowes whirled to a position directly in front of Mrs. Warburton, who seemed unsurprised by and prepared for this result; she seemed even satisfied.

“Mr. Finley,” she said, “I have to disqualify you.”

Bowes leapt again. “Yes!”

I protested. “Why?”

“Because I call this, ‘The Annual Paper Airplane Competition,” she answered with that indefatigable smile and with emphasis on plane. “Only airplanes are permitted to compete.”

Bowes, secure at last in his standing, left Warburton to shout congratulations at his cup.

I hadn’t given up. “Well, but what’s a ‘plane’ though? You never said.”

“I encourage you to look it up. Whatever you find there, it will not be anything like Mr. Finley’s entry.”

From the bleachers came a professorial objection in the voice of Mickle. “Isn’t the p