Choir

Published on 2017-02-15

On Sunday we wake up and find our bibles, then church lets out and the dogs are dead. The bodies are peppered across the Lowry field like fertilizer for spring prepping. Pastor Clay says something in the name of God, and then he’s shepherding the children back inside the church. The sky is made of gray cotton, and a southerly chill rolls across the field carrying the stench of wet fur and blood. Maybe even the dying echo of a mutt starving for breath as her lungs give out.

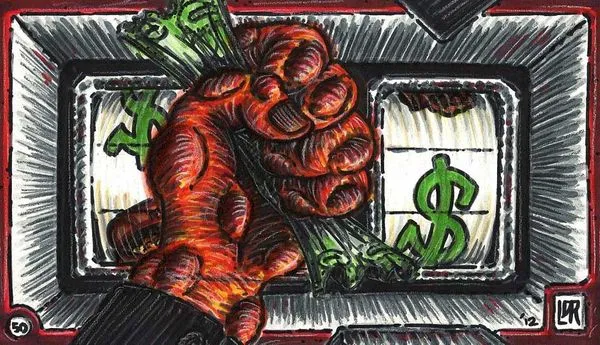

We didn’t believe in magic before Lucy Black showed us how. She has a way with needles, and in a town like Holbrook, where’s there’s no such thing as a straight flush and the only sacrament more sacred than Pastor Clay’s poker games on Saturday nights is his choir program on Sunday mornings, there isn’t room for such pagan talents.

Sheriff Bill Boyd unclasps his holster, and he says to no one in particular, “Nobody leaves the church until I say so.” He turns towards me, this same look in his eyes he wears on Saturday nights when the game comes to a close and he knows he’s walking away a lesser man than when he came. Same look his daddy wore when his money started falling out of his pockets—and you best believe it’s the same look his daddy’s daddy wore for the same reason. “What do you make of this, Paul? Gotta be more than thirty out there.”

There’s more than thirty in this field. Hell, there’s more than fifty. Looks like every dog in Holbrook is out there, dead.

“Gonna need you to come take a look,” Sheriff Boyd says demandingly. “Don’t know what this is, but maybe we can figure it out together.”

You always think if magic was real, if wizards and spells and flying broomsticks actually existed in reality, it’d be a world you’d want to be a part of. A world of excitement and adventure and wonderment. But this is simply not the case. Magic is utterly terrifying. It’s the language the devil himself speaks. Amid all the mundane and the lackluster way of things, you think maybe the grass is greener on the other side, perhaps a little danger never hurt anyone. But see, this is where most people get it wrong. Safety is not something that should be taken for granted. There’s no evil in safety.

In fact, there’s grace in normalcy. There’s mercy in normalcy.

Lucy Black came to Holbrook when no one was looking, and she started writing her spells on human skin. She wrote it on rebellious teenagers and frustrated adults who never had a chance to rebel when they were teenagers. She told them stories about the scars on her arms now drowned in dark ink, and those people started to think about everything they’ve never done but always wanted to do; about all those scars they haven’t gotten yet.

Sheriff Boyd keels over, and suddenly he’s letting go of a stomach-full of pretzels and communion and beer. The dogs are drained. Each mass is a sunken blob of bone and guts floating atop the mud. Lori Harris got a dog for her daughter’s fourteenth birthday in March—a boglen terrier-beagle mix. Mrs. Harris brings the dog in for a check-up, says this one’s special. They all say theirs is special. She spends a small fortune on this dog and maybe Samantha won’t sneak off with her boyfriend after school to go play in the dugouts. Hank hasn’t sat at the table in a month because Lori has her mother’s spending habits. “Damn disease is what it is,” he says. Now ol-Fluffy’s maxed-out in the mud.

It doesn’t take long before the coroner’s involved. He wobbles reluctantly from the direction of the church. The bags beneath Dr. Esau’s eyes are heavy from all these years he’s spent slicing and dicing in the basement of the Thompson Funeral Home. His khakis and jacket would smell of formaldehyde if not for the stench of crop fertilizer that drowns it out.

“See this?” Sheriff Boyd asks, holding the collar of his polo over his nose. He’s churning a puddle of thick, mucus-y blood beneath Mrs. Harris’ dog’s jaw with a stick he found on the ground. “Where’s the rest? She’s been sucked dry.”

Dr. Esau buckles his knees and touches the blood with the tips of his fingers. He massages the droplets with his thumb. Then he cranes his neck at the Sheriff in disbelief. He stands erect and places his hands on his hips and looks up like he’s breaking for air. “Some of the children saw. They’re terrified. They want to go home.” He looks at both of us and says, “And God, no. That’s not blood. At least not all of it.”

The blood’s tainted with petroleum distillate and alcohol. Dr. Esau says it’s the same ingredients you’d find in ink.

The bodies are an upside down graveyard and we’re smack in the middle. “Wait, do you see that?” says Sheriff Boyd, squinting at a mark on the underbelly of the the Harris’ family’s dog. “Jesus, that’s your name, Paul.” He turns in my direction, a familiar look of disbelief plagued across his face. “Paul Hownshell. That’s what it says, right there!”

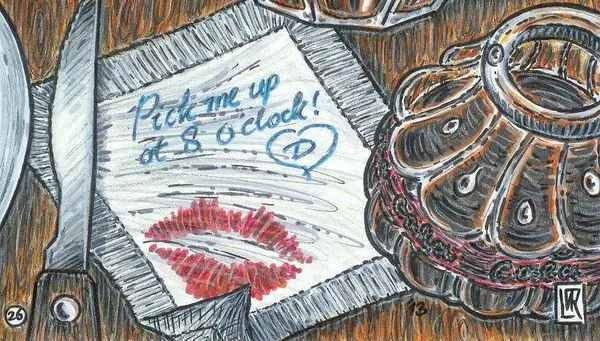

A town like Holbrook never knew lust before Lucy Black. Not real lust, at least. Not like the lust that’s talked about in that Proverbs verse, the one about not letting a woman captivate you with her eyes.

You learn to hate what you love most. And then you learn to keep this hate a big fat secret. At least until this secret tells on itself. This is what these dogs are.

The telling of our secrets—what we had done to Lucy Black in the privacy of our lust.

Sheriff Boyd is holding his gun with his finger on the trigger. His secret is a snake of ink beneath the sleeve of his shirt. We can hear the hiss of that viper sometimes at our poker games, and maybe the Sheriff knows that we know. But nobody talks about it. That’s not what those games are about, talk.

Dr. Esau wipes the sweat from the top of his bald head. He sweats when he’s nervous. And his teeth chatter ever so slightly. Always has. But then the good Doctor can’t see what we can see: the bronze dagger handle leering between the middle of his upper back, as if stealing a glance of the world not so secret. Then he begins to cry. His teeth aren’t chattering now. Instead, he’s a hunched gargoyle over a lifeless rottweiler, splitting its hind-legs so he can see its underbelly. “She said we’d pay,” he says, spit dripping from the corner of his mouth. “She was right.”

We all bore a mark, a symbol of the passing time we spent with Lucy Black, alone in her studio. Sometimes, in a town like Holbrook, there comes a woman who is simply out of the ordinary, who reminds us living just to live is just dying. It pays to put the cards down every once in awhile and have a little fun.

We can hear the children beginning to sing. Pastor Clay has stifled their fears for the moment. He’s an honorable Shepherd. On his shoulder is an articulate cross of ink, shaped with nails and detailed with blood. “A reminder,” he says, “that we have been bought.” Pastor Clay fell for Lucy Black just like the rest of us. He called her a special kind of demon. Said he might have even loved her. But he never hurt her. Not directly. Pastor Clay stayed home that night, said we’d play the game the following Saturday, that he is a married man, and lust is a sin.

The choir builds as they near the chorus: “We confess to him, he’ll remove all wickedness…” The tattoo on my left arm begins to burn fresh, as if it is new. “The blood from Your son will wash me from my sins…” the song continues. Suddenly my shirt turns red, and it can’t be stopped. And then we hear her voice, singing, “Clean this house, from the inside out…” She’s laughing now, continuing, “Restore me, take away my impurity…” Her voice dances in the wind. It’s beautiful. And it hurts deeply.

The singing stops. For a moment, the wind coming up across the field is all that speaks. Then the children scream from inside the church as Pastor Clay’s Sunday best begins to bleed with the rest of ours. A shepherd is responsible for his flock, is he not? If his sheep go astray, can he not bear part of the blame?

“Why the dogs?” Sheriff Boyd asks, his face stone white. “Why the hell did she do this to our dogs?”

Because it was my car we showed up in that night, right? I’m the one who brought us together. Because I told her I loved them, is my response to the Sheriff. Said I’d die for each and every one of ‘em. Said that’s my duty, that’s what people expect of a veterinarian. She smiled at me, and said I was a gem. Would you have done it had I not offered to drive, Bill?

Then I tell Sheriff Boyd, Most girls love that speech.

Fact is, Lucy Black has a beautiful way with needles, and this winter, some of us had a terrible way with Lucy Black. All these months go by and we think maybe she’s reconciled with what we did to her. Maybe it ended that night and nothing will come of it. We were wrong. Maybe she waited so we wouldn’t see it coming. Maybe she needed time to come up with her master plan—shame us in front of our families, our friends.

The blood beneath our clothes drips and then vanishes into thin air. I don’t have to wonder where the blood goes. Isn’t it obvious? Sheriff Boyd falls to his knees and blinks one last time. Dr. Esau apologizes over and over to himself like a man waiting to be judged.

Cosmic justice, is what this is. Without a doubt. Like the rest of the dogs, in seconds we’ll be blobs of bone and guts.

After everything we took from her, she has all the ink she needs to write her magic.