Faces

Published on 2013-08-13

Stephen lived amidst a crowd of faces.

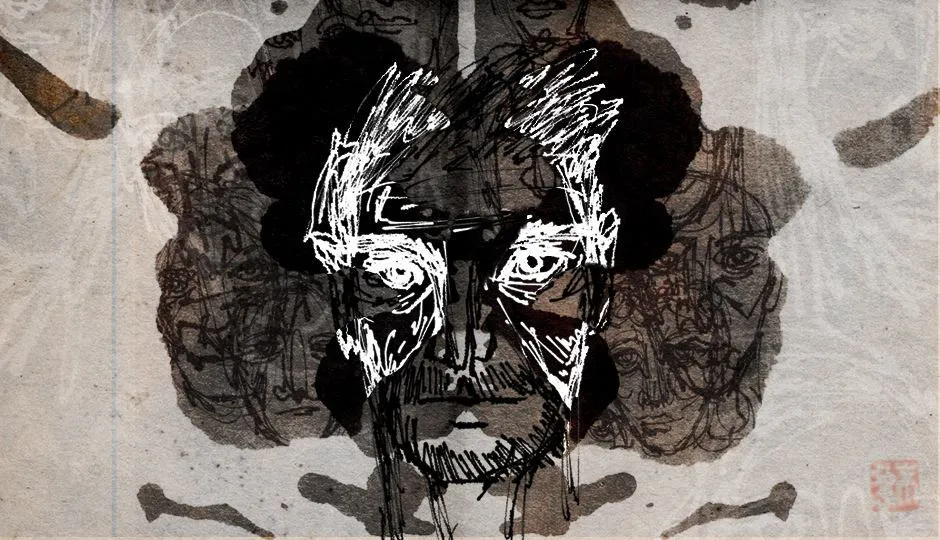

There were faces everywhere he looked. Faces in the pattern of a dress; faces in the cracks in a brick wall; faces in the clouds, the trees, the grass. Oh, and of course, almost as an afterthought, there were the faces of people.

He had started seeing the faces when he was very young, so long ago now that he could not remember the beginning of it. He could only remember being afraid of the faces in the wallpaper of his bedroom, of his screams when the light fell on it in a certain way, and how the faces leered at him, threatening. Then it had been the carpet, its loops of colour turning into the faces of animals or demons or nameless horrors.

In the end, his parents had taken him to a child psychologist. He had been given what he now knew to be a Rorschach test. In every random pattern of ink he had seen a dozen faces. He had only been five and he hadn’t understood the doctor’s diagnosis. Later, though, his parents had told him what had been said.

Stephen, it seemed, had a hypertrophy of that part of the brain which recognises faces. All humans tend to see faces in random patterns, but for some reason, Stephen had that tendency to an alarming degree. Everything in which a face could possibly be imagined was, to him, a real, living face, little different from the faces of his parents or of his playmates.

His parents stripped back the wallpaper in his room, painted it white, pulled up the patterned carpet and replaced it with a plain colour. It helped, but not much. The moonlit shadow of leaves falling on his wall was enough to start the screaming again.

As he grew older, he eventually learned not to fear the faces he saw; learned to suppress his reactions when he saw new faces in the drizzle of rain down a window pane, in spilled ink, in a pile of rubbish in an alleyway. He couldn’t stop seeing the faces, but he could learn to ignore them.

By the end of his teens, managing to live what most would call a normal life, there was an incident which revealed a new side to his disability. He discovered that his disability was also a talent.

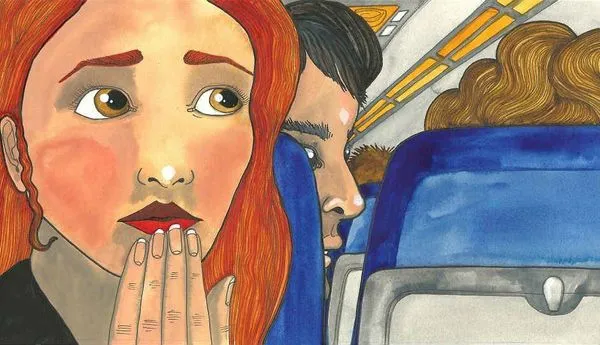

Walking down the street one morning, on his way to college, a woman a few metres ahead of Stephen screamed and began to struggle. A hollow-eyed teenager wearing a hoodie was pulling at the woman’s handbag, trying to get it away from her. As she continued to resist, he pulled out a knife and slashed the straps, but she jumped forward to grab the body of the bag. That was when the youth stabbed forward at her chest with the knife and she gave a kind of sigh, let go, and sank to the pavement. The youth was off in a flash, dodging down an alley, and was out of sight before anyone could give chase.

Stephen was among many people who tried to help the woman, and an ambulance was called, but by the time it reached the scene, she was dead.

Stephen’s name was taken, and he was asked down to the police station. Could he describe the youth? He found the question incomprehensible. Of course he could, and did so in minute detail. Later, at an identification parade, he picked out the youth without pausing. As a witness in court, he was confident and not to be shaken by the defense attorney. Although he had to concentrate, so as not to be distracted by the faces of monsters and demons he could see in the pattern of the man’s tie.

“Are you certain?” he was asked again and again. He was almost baffled by the question. How could anyone not remember a face?

The court case attracted considerable attention, due in part to the local newspaper’s promotion of a law-and-order agenda at the time. Through that, Stephen’s testimony drew attention, too.

A few days later, he was contacted by someone who said he was recruiting for a government agency, looking for someone with certain talents. Stephen, still uncertain as to his prospects after college, readily agreed to attend for an interview.

It wasn’t much of an interview, really. Instead, they asked him to look quickly at a blurry photograph, apparently taken from a distance with a telephoto lens, with the man’s face partly turned away from the camera. Then he was given a huge book containing thousands of photographs. It took him some time only because there were so many pages in the book. But the moment he turned the right page, he reached out and pointed to the man who had been in the blurry photograph.

The fact was, he never forgot a face. Once clearly seen, for however brief a moment, he could identify it again years later, even when under a disguise, even after cosmetic surgery. His memory for faces, it seemed, was vast.

He was recruited on the spot and he dropped out of college.

The next two years were good for Stephen, and it seemed that he had found his place in life. The pay was good, and the job endlessly interesting and, for someone with his talent, not hard to do.

But then something seemed to go wrong. At the age of 22, the voices started. The faces began to talk to him.

Almost every day, his job involved looking at hundreds of photographs of people. They began to speak. At first, it was just one or two, saying hateful, ugly things. Then he would turn a page of an identification book and a dozen faces would call out to him, telling him he was worthless, or urging him to carry out his own acts of terror. Then it was all of them. Voices with a hundred different accents, a babble of violent words, counselling despair or violence.

He tried to regain control, suppress the voices the way he had learned to control his reaction to the faces in the carpet or the bark of trees, but he struggled. He took leave from his job, to get away from the books of faces, but now every face he saw in the random patterns of the world called out to him in the same way. The faces in the clouds, in the ripples of water, in an arrangement of flowers; they had never gone away. And now they were no longer silent. It was like always being in the midst of a noisy crowd, a mob.

He should have sought help, he knew, but he remembered only too well the professional indifference of the child psychologist when he was young, remembered the laughter of his playmates when he tried to point out to them the faces he saw.

Everywhere he looked, there was a face, and now every face spat out the same message. He was worthless, and the only way to redeem himself was to carry out an act of bloody revenge against the world.

He had learned much about the methods of terror through his job.

With the cacophony of faces urging him on, he began his preparations.