Erasing Charlie

Published on 2013-03-29

Charlie landed in a slightly shabby, twin-propeller plane, scurrying across the tarmac through a rainy mist into a large, deserted terminal. The taxi driver only grunted when he gave the address, and by the time he checked into the hotel, he’d forgotten where he was. Cleveland maybe? Milwaukee? The hotel was a seven-story sandstone building on an otherwise deserted block, the other buildings there razed long ago, lots grown over in broom grass and debris. A claustrophobic lobby and long, dimly lit halls of identical black doors.

He’d barely unzipped his suitcase, searching for the pint of bourbon he stashed there earlier in the day, when the telephone in his hotel room rang. He stared at it, did not answer. He’d made the reservation himself; no one knew where he was. Just as he found the bottle, it rang again. He picked it up.

“I thought you were avoiding me,” said a female voice, husky, with a hint of irony.

“Who is this?” There was a mechanical ticking noise coming through the line.

“This is Carla,” the voice explained. “The agency sent me to pick you up. For your appointment.” The agency? Did she mean his publisher? If so, this would be a first. The company had done little more than give him a list of cities and dates for his book signings.

He was told he would be reimbursed for his travel expenses, but so far he hadn’t seen a dime. His complaints about this to a bookstore owner in Memphis brought only an evasive shrug.

“My appointment isn’t until tomorrow.”

“Do you want me to come back tomorrow?”

“Yes,” he said, growing exasperated.

“I’m in the lobby.” She paused, then added, “Maybe I could show you around?”

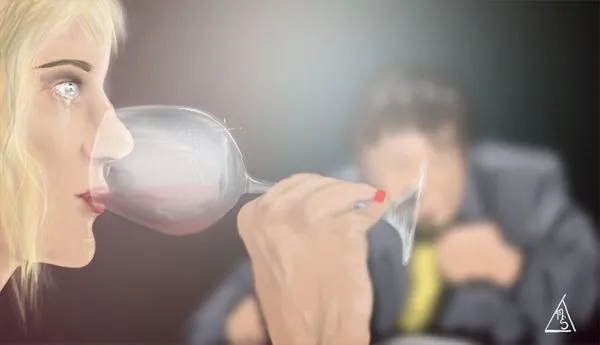

He couldn’t remember saying yes, or hanging up the phone, or even leaving the room. Yet there he was in the hotel’s bar, empty save for a Pakistani bartender watching cricket on TV, with a perfectly lovely woman, black, pixie-cut hair; arched, plucked eyebrows; a dress of softly folded fabric hiding a slightly overweight frame, talking about the practicalities and pitfalls of genetically modified food, which also happened to be the topic of his book.

“But is it really so bad,” she asked, her ever-encroaching hand now grasping his wrist, “if it helps feed the world?”

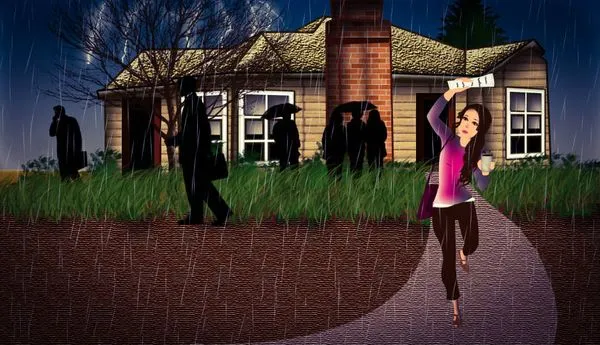

“That is the question,” he wanted to say, but his head was swimming again, as if he had stumbled into a pool of black, inky water. The bartender was staring at him impassively as he grabbed onto the railing of the bar and then he was in the back seat of a car driving down deserted streets, block after block of dilapidated row houses and Jewish delis, dry cleaners and corner groceries with neon-lit windows, Carla talking to someone in the front seat. The car came to a stop and Carla led him by the elbow into a two-story row house.

The inside of the house was recently renovated and well lit. A frail elderly man with a full head of dyed black hair and oversize glasses sat at the table underneath a crystal chandelier inside the formal dining room to the left of the front door. “Come in,” he motioned with frail, bony fingers. “I’ve been waiting for you.”

Through the fog that still shrouded his mind he recognized the man. Benton MacDonald, CEO and board president of MacDonald, Esterhaus & Byerly, commonly known as MEB, a multinational agricultural biotechnology company and the largest producer of genetically modified seed in the world. He had tried to interview the man for his book but was escorted out of their corporate headquarters by a platoon of black-suited thugs. His shoulder still hurt from his rough landing on the New York City sidewalk.

Carla led him to the table. “You drugged me,” he accused, his hands resting flat on the table’s dark-grain mahogany. “You can’t kidnap me!”

MacDonald’s eyes widened in false shock, the magnification through the oversized lenses turning his pupils into giant and soulless black orbs. He and Carla shared a chuckle. “That’s quite a serious accusation,” he said coolly. “A serious accusation for such a naughty boy.”

His stomach clenched. MEB did bear the brunt of the criticism in his book, which profiled a Kansas corn farmer whose farm was beset with a series of mysterious disasters and financial setbacks when he refused to use MEB seed. And it included accusations of intentionally falsified MEB tests submitted to the FDA, the information attributed to an “anonymous source” because the scientist who told him about the tests said she feared for her life.

“My publisher will be looking for me,” he stated.

Carla, now sitting beside him, stifled a snort. MacDonald smiled kindly. “We own your publisher now. Bought the company two days ago.”

“People will worry when I don’t show up for my signing tomorrow.”

“Oh, you will show up for your signing tomorrow. Or at least a slightly more handsome version of you will show up, a version, I must say, who is more eloquently conversant about the tremendous scientific advances MEB is creating to address shortage issues in the world’s food supply.”

Panic overcame him. With wobbly arms he pushed himself away from the table and then was floating through a black, starless sky over city streets and past forest and fields and into a burning red sun. He awoke on the forested shore of a large, gray lake, ducks cackling overhead, frogs gurgling and chirping around him in the cool morning mist. Someone had removed his shoes. The only thing in his pocket was a note card of heavy white stock, on it scrawled in plain Courier type the words, “Don’t Fuck With MEB.”

Only after walking on cut and bleeding feet for hours, the lake still vast and gray on the horizon, sky growing cold and ominously dark, did he realize he could not recall his own name.