The Virus

Justin Ordoñez | Sayantan Halder

Published on 2013-04-06

I

As a doctor, Lucille stopped seeing people as black, white, fat, thin, a woman, a man, Hindu or Catholic long ago. Only two categories distinguish humans to her. “Infected.” And “Not infected.”

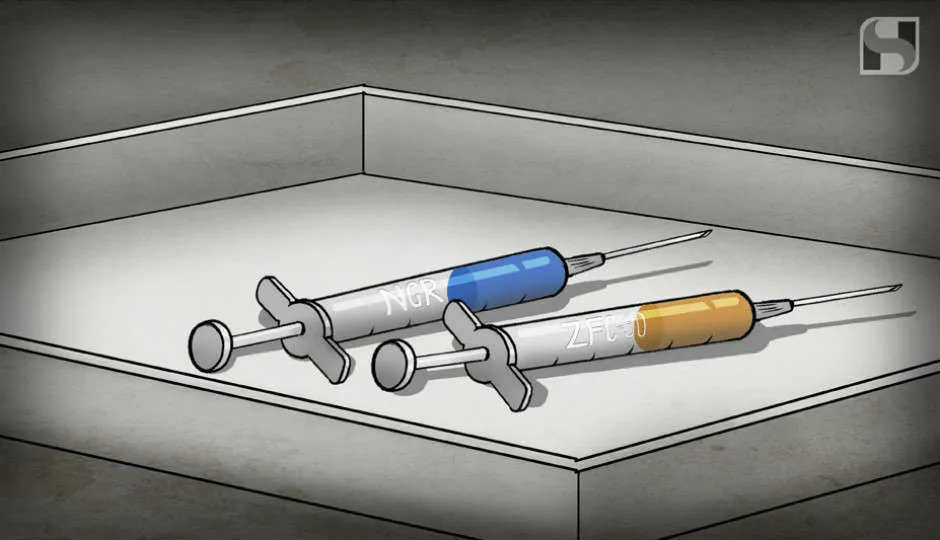

The not infected are the primary priority, and the infected are no longer persons. They are simply patients. Her work on the NGR virus—a super-virus created for the purposes of war, and released against its creators for the purposes of terrorism—has necessitated this detachment. If every patient she saw with warts, legions, rotted skin, and several musculo-skeletal impairments were human, if she had to feel for them, all of whom eventually die, it would be the only thing she did.

Now it’s different.

In his white lab coat, in a door frame, backlit by the hallway’s fluorescent lights, Grant strains for words. “Lucy, I’m… When I heard, I…”

Lucy answers. “I appreciate you visiting.”

“If you want to stop working, deal with this…”

“It was never an option to stop, especially now.”

Lucy leans her wrist into her forehead, looking down. Tucked beneath the covers, at the bedside where Lucy sits, an eight year old girl, Isabella, is sleeping a single hour of sleep before the pain medication wears off, before she awakes to push a button and escape once more. The first signs of infection—dry, flakey skin like shingles—descend from her forehead. Many tubes collapse into a central line into Isabella’s neck, delivering a cocktail of suppressant medications whose side effects will ravage her, and perhaps a death worse than that of the virus itself.

Isabella’s bed is wrapped in heavy, transparent plastic.

Lucy presses her hand against it. “I wish I could touch her, Grant. I wish she didn’t have to be alone.”

II

The disease acts fast. In the weeks that follow, Lucy acts faster, telling herself: You have to finish the ZFC-90.

ZFC-90 is the latest variation of a NGR viral inhibitor. A year ago, a computer model projected that ZFC-90 would eradicate NGR from a living organism. Finally the correct chemicals had been identified; the mystery now was their correct balance. Previous versions of ZFC had left patients in coma, in delirium, and in some cases deceased. The set-backs were frustrating, and confidence had waned, some of Lucy’s colleagues calling for alternative solutions. Throughout, Lucy kept resources invested in ZFC-90. When she first saw the computer projections, she felt certain the ZFC was the key.

Her devotion to the ZFC is sometimes mocked. Today, it’s being outright questioned.

“Admit it, you’re obsessed,” says the young male doctor, another brilliant mind exhausted from failure. “You never leave the lab. Do you even sleep?”

Lucy answers, “Why don’t you get some coffee and cool off.”

“You’re too close to this, Lucy! Your daughter is affecting your judgment!”

A colleague encourages the young doctor to leave the room.

Hours later, Lucy still works in that room, tired from the endless string of days that have lost definite beginning and ending. Sometimes when her eyes are too tired to read another report, or to watch the computer list additional administration scenarios for the ZFC-90, she reviews her career. Fifteen years at the NGR project, starting as an intern, and now the project leader. Throughout, she’s seen a persistent progress towards a vaccination, but the break-through has never come. She wonders if she missed something, if she made some critical error, maybe she overlooked the cure, and this is the punishment for her poor judgment.

This is God losing His patience.

Grant enters. “Lucy, everyone’s moved by your devotion, but given Isabella’s condition, it’s time for you to take a step back.”

“You’re firing me, Grant?”

“We are asking that you spend time with your family.”

Lucy pounds her fist into the table. It is one of several small outbursts that Lucy’s had in the last weeks. “What time I have left, you mean?”

III

The vacation is three weeks mandatory. During that time, Lucy works obsessively on the ZFC-90. The NGR beats her every idea, always adapting to vaccination. Eight days in, she pairs the ZFC to a different molecule, leading to positive computer projections. She tweaks and re-tweaks the details, visiting Isabella while the simulations run.

The suppressant medications are becoming increasingly ineffective for Isabella, and her skin has broken out in spots, her muscles turning to string, and her temperature at a constant state of fever.

On Lucy’s first day back, the research facility has a “Welcome Back!” sign hung, and everyone is happy to see one another. Lucy is about to call a staff meeting to share her progress on ZFC when she notices it’s missing from the agenda.

Lucy’s office is a mess of boxes full of binders, degrees on the wall, and a fake plant or two. She grills Grant. “How could you not tell me that you’ve stopped working on the ZFC?”

Grant is calm. “We’ve simply set it aside. We’re not giving up on it.”

Lucy pulls out some of the files from home. She hands them over to Grant, and he lazily flips through them. “Grant, I know the board only sees a crazed mother, but give me two weeks, I’m telling you, as a scientist, the ZFC is the answer.”

Grant sets the file on the desk. “You mean it’s the last real shot you have at saving Isabella’s life.”

Lucy explodes. “You don’t know that!”

Grant waits as Lucy awkwardly moves her arms, composing herself. He says, “Lucy, the medical board wanted you removed from the project. I told them with some time off you could handle this, but…”

Lucy interrupts. “We need to synthesize the ZFC-90.”

Grant asks that she wait in her office. Twenty minutes later, he returns with the top administrator at the hospital. Lucy is informed of her removal from the project. They escort her off the property, promising to mail her belongings.

That evening, Lucy breaks into the office by telling a janitor that she forgot her badge. In the dark, she synthesizes the ZFC-90 into an injectable solution. When the ZFC-90 finishes its synthesis, a clear liquid indistinguishable from water, she loads it into one of a pair of syringes.

Grant and a security guard bursts into the office.

Grant says, “Lucy, the janitor’s already told us how you got in here, now I want you to put down whatever you’re holding.”

“This is it, Grant. This is the ZFC-90.”

“Lucy, I can’t let you give Isabella that.”

“Give it to Isabella? You think I would give it to my daughter untested?”

Grant concedes. “Then, what is your plan?”

Lucy holds up the second syringe. “This is the NGR. I’m going to inject myself and this room is going to become an infected zone. You need to clear out.”

One of the security guards instinctively un-holsters his gun.

Grant holds out a hand. “Lucy, that’s enough to kill you within a day, to wipe out an entire state if it gets free.”

Lucy bites off the plastic cover on the NGR needle, stabbing it into her neck. “I’m going to do it.”

“Lucy, don’t…”

Lucy flexes her thumb, the viral solution injecting. It hurts. Lucy stumbles. No one notices. Grant and the security guard are running for their lives. Lucy sits on the ground, pulling the needle out. She wishes she had time to see her daughter once more. Or maybe, she thinks, looking at the ZFC-90. This isn’t good-bye. It’s too early for the virus to have beaten her system, but Lucy feels like she is already dying of it. Weaker by the moment, Lucy removes the protective sheath from the ZFC-90, and in about the same place on her neck, she injects the second needle.

IV

Lucy’s vision is fuzzy when her eyes open. Though, she knows the lights are on. A random beep fires off here or there. In the distance, she hears a TV. Feeling in her body returns bit by bit, and all she feels is soreness and sickness.

Grant is above her. “I’ve got to hand it to you, you stuck with it until the end.”

“What’s… What’s happening?”

The momentary confusion in Lucy is replaced by a rush of memories. Fifteen years of fighting the virus. The year of fighting it for Isabella’s life. The pair of seconds it took to inject herself with NGR, then with the ZFC-90.

Grant smiles. “It’s working, Lucy. Your daughter, Isabella—she’s going to live.”