The Mannerisms of a Broken Fork

Matthew Kabik | Sayantan Halder

Published on 2014-01-02

Amy didn’t have a pinky finger.

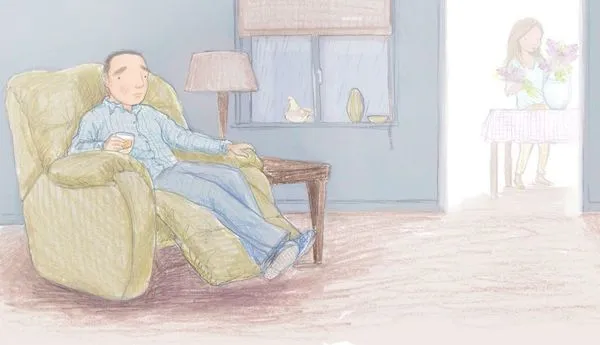

It bothered him at first, she seemed proud of it almost, she’d refuse to use her five-fingered hand to hold his or move stray hairs from her eyes. She’d always use her left hand, malformed and startling. But that was only in the beginning of their relationship, after six months the missing digit became something like a comfort to him—he’d notice its absence in his palm and feel loved. It was something he couldn’t explain to anyone else, and that also made him love the missing finger even more. A secret between them both.

He couldn’t talk about it, though. He wasn’t sure how she lost it or if she ever had it to start with. It was the only taboo in the relationship, the only unspeakable. It didn’t bother him very much, the not knowing. He wasn’t a curious person. He’d occasionally slip and begin to ask, but mostly caught himself. When he didn’t she’d get quiet in company or furious in private. He’d let her storm away and wait for the broken comb of her hand to run through his hair in apology.

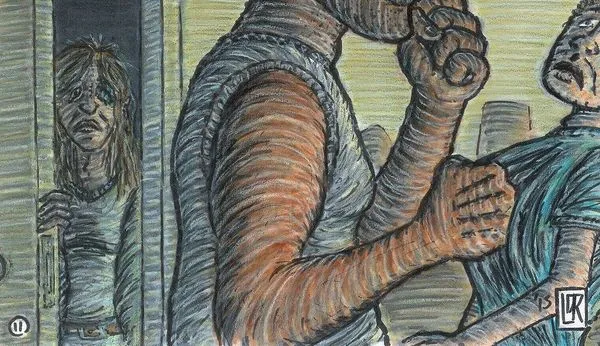

They broke up over a mistake. His mistake. Amy created an argument over who should do the dishes, and he lost despite his best effort to point out the amount of hours he worked. In his anger he stabbed a fork into the wall behind the sink, making more noise than what he expected and bringing Amy from the living room. She didn’t say anything, she didn’t even look upset, just confused. When he pulled the fork out two prongs stayed in the wall, so he tossed the utensil into the trash.

She was still staring, and he felt awkward and ashamed. He told her the prongs were in the wall, what good would a two-pronged fork be for anyone?

There wasn’t any talking after that. She simply packed a backpack and went to her mother’s. The next day Amy’s brother and father came by to collect the rest of her clothing and books. Neither looked mad, though he couldn’t figure out if they were truly indifferent or if silent rage was a family trait.

He painted over the mark in the kitchen wall a week later, leaving the prongs embedded into whatever they sank into. He fished the fork out of the trash and kept it in the silverware drawer, underneath the utensil tray. He’d take it out occasionally—running his finger into the jagged groove of the missing pieces. He’d try to feel what wasn’t there anymore.