Summertime

Published on 2017-01-04

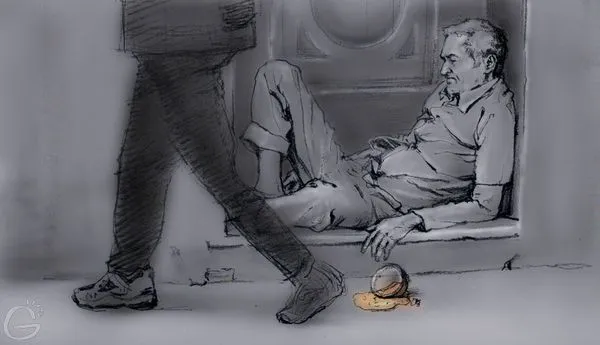

Early in the morning, Wallace, Meg’s husband, went up a ladder to the rooftop to remove a bird’s nest clogging the rain spout. Later he jimmied off the wooden frame hanging over the basement door, which took some time. The wood was rotting and rainwater was seeping into the basement’s walls and onto the floor. Meg stayed at her piano. Wallace passed her in her piano room as he left the house an hour later, calling out, “I’m going to Home Depot to buy caulk.” He came directly home fifteen minutes later and caulked the gaps he’d made where he’d removed the door frame.

Just a week ago the air conditioning system had backed up with fluid and leaked onto the basement floor. For two hours, Wallace had soaked up the puddles with every single towel they owned. He’d brought Meg down to show her the mess and she’d shaken her head. She helped him carry the towels to the dryer, said, “Excuse me,” and sealed herself off in her piano studio.

The a.c. repairman came after Wallace wrangled two weeks for an appointment, by which time the weather was sweltering. He banged for an hour with his hammer, cleaned the tube with a noisy vacuum and then, whistling tunelessly to himself, threaded special paper through it to redirect the fluid. Meg remained at her piano, putting up it, waiting for the racket to end.

The repairman told Wallace there could never be a perfectly tight seal again in the unit after such alterations. After he left, Wallace covered a number of tiny gaps with sturdy silver refrigerator tape. Afterwards, he made afternoon coffee and sat at the kitchen counter with a cup. He cut up a sour green apple and ate it contentedly.

“What’re you practicing?” he shouted to Meg. Her piano room was two rooms away from the kitchen. She didn’t answer him and Wallace didn’t try again. He washed his coffee cup, went out to the garage and stapled down a warped section of the rubber strip the garage door opened and closed onto that kept rainwater from getting in.

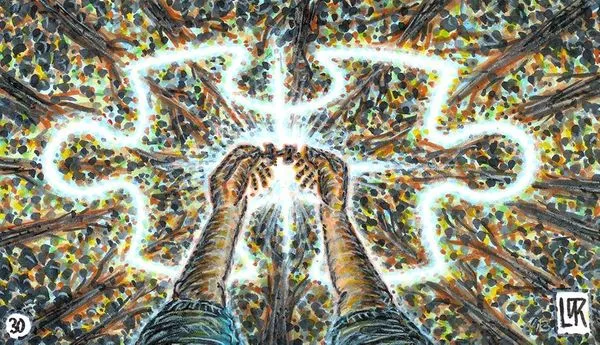

That same day, late afternoon, he went outside ahead of the rain. July thunderstorms could be counted on. He pulled weeds from Meg’s petunia and herb beds, trimmed the hedges and clipped branches off the two front yard trees, to give them back their shape. Meg looked out on these trees when she played the piano. He saw her now and felt peaceful. Glancing up, he noticed the upstairs shutters needed a touch-up. He found leftover paint in the garage but it had dried up.

“I’m going to Home Depot again,” he called through the front door, which he’d kept open. The neighbors should enjoy Meg’s playing.

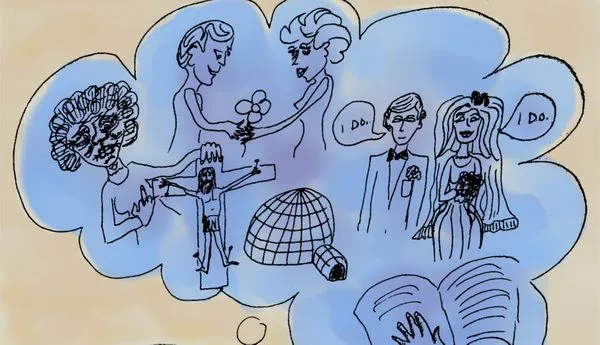

As a project that day, Meg had decided to research the use of ninth chords using a theory textbook as her source. She loved the big, gaping, open-ended quality of ninth chords. She took frequent breaks lying on her back staring at the ceiling on a shaggy rug or in the fetal position on her couch. The excerpts she’d played that revolved around the use of ninth chords both thrilled and exhausted her for their power. There was Strauss’ Artist’s Life Waltzes, Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, Grieg’s Grandmother’s Minuet and Wedding Day at Troldhuagen; Schumann’s Kinderszenen, Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Faure’s Apres un Reve.. Intermittently she also practiced two pages of Chopin’s F minor Ballade, which required slow, exacting repetitive work that tried her because this kind of practicing made her terribly aware how limited, clumsy and inefficient corporal human beings were, and how hard everything was. Everything she played was lush and haunting and filled the house with beautiful melodies and harmonies, but both the ninth chords and the Chopin also had a way of prodding things open inside her a bit too much, and her regrets came pouring out with the notes. Ninth chords had a certain hard-edged, raucous sonority, too, even while they served to keep the music fluid and forward moving.

There was a text that went with the Faure which read, “You called me and I left the earth to fly with you toward the light. The skies half opened their clouds to us, partially revealing unknown splendors, divine lights…It made Meg sad this was all she could do: sit at the piano, living those words vicariously, through fingers, wrists, hands, arms, the heart, the groin. But she read it several times, loving it, too.

Early evening, a cloudless, humid one, she and Wallace drove out of the suburbs to the city harbor. They both wanted to see the water. They strolled past a group of newly built, high-end waterfront condos, trying to see in. They’d each have their own separate one, of course, and a third, as a spare. It began to sprinkle and then rain hard. They ran from their daydreaming back to their car. They had a house, patched, re-sealed, kept up with, held together, waiting for them.

“We’ll soon know if there are any other leaks,” Wallace said through the thunder, just as Meg leaned over slightly and put her head in her hands. He slammed the car door hard when they pulled up to the house as he always did when he got out. The force shook the entire car just as Meg was getting out her side. Meg covered her ears in a fright or flight stance.

“I so hate that,” she thought placidly, linking her arm through his as they crossed the lawn and Wallace admired his handiwork on the trees.