Miss Missouri

Published on 2013-04-10

Begin by answering the phone, reaching into the mailbox, visiting your mother. Maybe you hear it over the radio. Watch a late-night special. Read the back of the non-fat milk carton. Outside your building, your mother will apologize repeatedly. She will cry. She will have had her long grey hair cut short. A gesture.

Four years, one month and three weeks. You left your daughter, husband, and high school sweatshirt in a dusty village — village, really — in east Missouri. Your mother tells you that you will have to go back. She’s full of bright ideas these days. Feel abandoned, frozen, terrified, frantic, and the hottest little brushes of rage. When desperate or alone, walk to the grocery store. Stare at the backs of milk cartons. Blink at her name, age, height and wide eyes or, alternatively, hurl the stupid Missing Person ad to the ground. The night manager drops your arm when he figures out you’re the kidnapped girl’s mother, or he fizzles out of the room when the police officer fills him in. Either way, they tell you that you get to go free and you spit on the parking lot floor. Four years, one month, and three goddamn weeks, but you’ll never be free.

Make attempts at finding your ex-husband. Remember: you left him not the other way around. The operator will ask you for the city and state, please. Tell him bitingly, bitterly. Add: it’s a hellhole, a fucking waste, I mean home and all, but a pit. Devotion, deep-rooted and hot, laps at your insides. Explain the lack of options, lack of exhilaration. Plan not to hang up until the call goes through, but have a text message of the number sent to your phone just in case.

And yet from time to time you will stare into the bathtub or a random tube of lipstick and bask in the life you have cultivated. You will feel nips of contentment, exultation, joy. Four years, one month, three weeks, and this is your family now. Let’s say your father is a troll. Your ex-husband is a magical turnip. Your high school classmates are spirits of the netherworld. They all still live in that primordial tar pit together.

Lie. Tell your ex-husband you work in a museum, one filled with taxidermy animals. He wants to know about health risks. He wants to be sure that you’re, you know, all right. He breathes heavily into the receiver. Lie, repeatedly. Say you never have to work night shifts, that your darling grandmamma of a boss never makes you. Darkness. Glass cases. Chrome door panels. They all still scare you. He wants to see you. He wants you, ravenously. Do you still only fly United?

Don’t put on music. Don’t wear lingerie. Take off your clothes, shyly. It’s a craft. You will lie on the bathroom floor naked, watching, your fingers beseeching bare skin of his insecurity. Hair: fool away from his face. Buttons: charm out of their hidey-holes. Chuck his shirt in the corner behind the toilet. Roll him over on your old bathroom floor barely three hours after your night flight lands, just past dawn in Hell.

Go to the front porch. His neighbors. Everyone will look at you and then go back to what they were doing. His best friend’s wife will be jostling a toddler over her shoulder as she walks past. She will introduce herself as Tammy. Try not to laugh. She will want to know if Harold is home. She will ask you, “Are you house-sitting for him?” Faintly, distantly, she’ll remember the junior prom when you stuck celery sticks and Ranch dip down her dress, and look quickly away. You’ll smile. The toddler will spittle over the back of her pink and yellow blouse: gurgly, gaping mouth and hazy eyes push up into her neck. Feel sated, to the point of excess. “Is Harry home?” she’ll ask you again. Smile. Shrug. Swat the door shut behind you.

It intoxicates you. Self-satisfaction. A slurp of tequila. When you pass women your age on the street, giggle and stare them straight in the belly button, straight in their bulbous, lactating breasts.

In the kitchen that weekend feel loud and relentless. Sit on the counter and tell him he’s ugly. That you bet he doesn’t know shit about cars. That you’ve come back to find him freckled and spineless. He will give you a momentary view of his hunched back, vertebrae poking through his shirt almost like fingers stretching through a balloon. He will start to shake. Rub your hand up and down his arm. Run your fingers through his hair.

When you get out of the shower, damp and smooth-skinned, conquer his chest with hard, heaping bites. Trace your big toe against his ankle. His inner-knee. His uniform is slopped over the bedpost. He will push you so hard you stumble and smack onto the floor. Say something like: What the fuck is wrong with you? Or maybe that’ll be his line. Go back into the bathroom. Tighten every cap.

This will be the tough part: her name repeats on the radio, at least on the station your ex-husband always plays; her name, age, height. On restaurant windows you see the posters. In line at the pharmacy you get furtive looks. They form a support group for you. They touch their own children’s heads. Bang the toe of your boot on the corner of the pew on accident. A cuss shoots through your lips like a little fish. He ducks his head and rubs the back of his neck, standing in front of the pastor sputtering search plans and statistics. Stare him down the next Sunday. Dare him to invite you to church.

He will seem to be drinking Vodka, tentatively, glancing quickly at you for approval.

At work he will spend company time in the exercise room.

He will ask you if you want to go to the fair.

He will ask you what the symbolism means.

Well?

But this is your home, he will say, in a voice that rights wrongs and slays dragons, that dies off after the Middle Ages or maybe exists eternally in the bottom drawer of the pantry where you keep plastic bags for unforeseen situations that might require plastic bags, a voice that shoves the door open with its head, knocks back its visor and wails, knocks you out of mental tangent, wailing: How long has it not been enough, why didn’t you tell me it wasn’t enough?

Next there are eyewitness reports. Sightings: Barton, Benton. He will pound his fist onto the kitchen countertop, phone pressed wet to his face. A gust of hot wind blows into your eyes and your nose spasms.

This is no time for miracles.

There will be police interviews, statements and co-signatures. There will be nothing for you to do. He has already posted signs everywhere conceivable: on desktops, over freeways, over other signs. Someone will call from the police station: relatives’ names, phone numbers, addresses needed. Ask where his parents live nowadays and he’ll just go grinning from ear to ear. Smile back. He will laugh at something, hours later, completely unrelated. But wheezing. Rioting. Roaring at the television screen in the next room. Bolt in and ask him what’s wrong. Roll together on the floor in front of the TV stand. Afterward, there is nothing else to be done. Afterward, he will dangle half off the rug, completely used.

There is never any news, just a telephone rocking endlessly in its cradle.

Fantasize about a dead body. It is a study in exhaustion, an examination of the end of the rope. You would be comforted by his bony sister and his sobbing ex-girlfriend. The three of you in the depths of the morgue would hurl yourselves at the steel table, then surge backwards. You, especially, would kick your feet, stumble and howl, bare your wrists. Your mother would be proud.

There is never any news, just a telephone wailing endlessly for its mother.

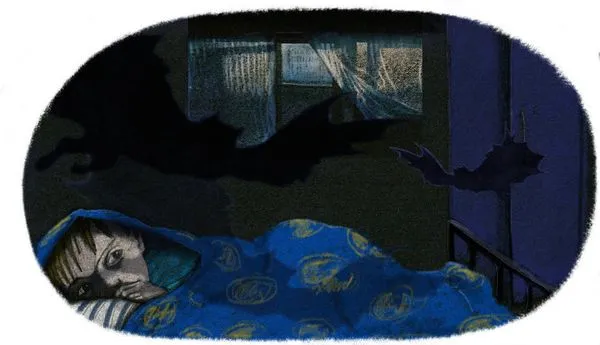

At night you will be anxious for the weather to warm. You will pace the front porch like you are waiting for a package, for justice, for sunrise. He will not wait up for you.

There is never any news, just the phone sucking absently on its toe.

You will never see him again. Or maybe you will, whatever. But her you’ll see daily. Her picture you put on your refrigerator, above your mantle, clamped in a locket. It becomes a conversation piece. When men come over, they ask questions. You tell them you named her Agatha, after your grandmother, after your best friend in college.

The phone will roll and roll in its cradle.

Four years, one month, three weeks, and so much more. They found her bones buried three miles outside of town. Call your mother back. The sun rises outside your window, out on the curb. The fog rolls in, but it dissipates. One of those mornings.