Wings

Rose Engelfried | Terri Kelleher

Published on 2013-04-25

The red-tail came in that morning in the arms of a gold-haired young man, ten minutes after Lynette climbed out of Brad’s silent car and slammed the door so he could drive away. The hawk’s left wing hung at a sharp angle and two bullet holes still oozed blood. Her wild eyes flickered to Lynette’s face and the hoarse scream of that open panting beak echoed even after Dr. Stein placed the plastic cone over the hawk’s face and the bird had fallen into the limp silence of anesthesia. “Hold this,” Dr. Stein said, and Lynette held the cone in place the whole time the bird was down. Each time a machine blipped Lynette’s heart wanted to stop. Dr. Stein had the bullets out and the wing set in less than an hour. But birds were never easy. At Wild Rescue birds, more than anything else, just never woke up.

This one did wake up. Lynette lifted it, wrapped in a towel, and set it in the waiting plastic crate, and they both watched as the bird opened her eyes. She stirred, helpless, body and wings too drugged still to do what her brain ordered—flee. Besides, there was nowhere to go.

Outside sun blinded. Lynette still didn’t expect spring. Winter had died suddenly and shouldn’t, Lynette thought, have died at all. Last spring had been the first spring with Brad, when getting her Masters in biology had sounded like a good idea and she’d somehow had the time to fall in love. If it had to be sunny at least let it be cold, at least let the birds stop singing. That hawk in there could wish for winter too, wish the fool human who had shot her down had done so before eggs hatched in the nest, two or three mouths now gaping emptily at the sky. Hawks mated for life, whatever that was worth. Some father that hawk’s mate would have to be, to raise those nestlings alone.

Lynette took off her shoes, put on rubber boots, crossed the yard from the vet compound to the flight cages. Three hours’ worth of cleaning to do before Brad came for her. Three hours too long. She’d never meant to stay on at Wild Rescue, she’d gotten all the internship credits she needed. She had a Master’s thesis to finish. She didn’t have time to stay here cleaning up bird crap.

“Excuse me,” a voice said behind her. “Is she all right?”

She’d forgotten him, the young man who brought the hawk. He stood behind her as though poised for flight, his light brown eyes flitting towards her and away. A stray downy feather had caught in his tousled golden hair above his ear. He cleared his throat before he smiled at her, quick, and looked away.

“She’ll recover.” Lynette bent to tuck her pant leg into her boot. “There’s no knowing how much movement she’ll have in that wing when it heals, but you certainly saved her life.” The young man didn’t nod, didn’t answer, so she kept talking. “I’m Lynette.” She held out her hand.

He stared, then shook. His hand was big, he could have crushed her, but he didn’t. “Corwin,” he said, and let her hand go, and she saw the strength in his fingers, the muscles of his forearm. There was something about that grip, she thought later, and those eyes, that might have told her. She didn’t think of it then.

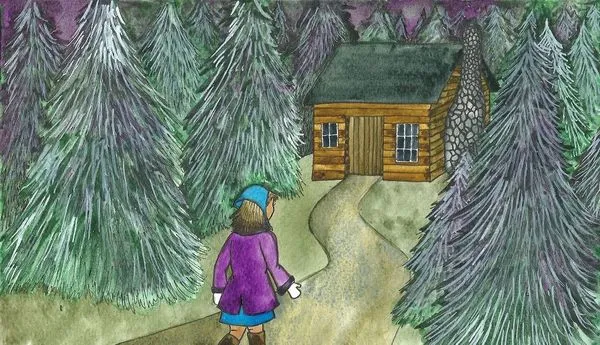

Corwin came back the next day. Lynette, head swimming in graphs and statistics of tree frog population growth, was scraping the last of a disemboweled mouse from a blind kestrel’s nest box when she saw him coming up the hill. She had a test in four hours. Last night she’d gone home and smelled an unfamiliar perfume in hers and Brad’s bed. She wasn’t thinking about Corwin. He trudged up the hill carrying nothing. His bare feet moved confidently over sticks and leaves. The wild look still shone in his eyes.

“She’s doing well.” Lynette tidied away the mouse—visitors were easily disturbed. “I’ll take you to see her. She’s in the small flight cage, she’s getting around.”

Corwin followed her, first to the kitchens where she found the hawk’s food waiting in Tupperware on the counter, then out to the flight cages. The hawk sat on the darkest corner perch, her fierce eyes taking in everything. Lynette went to the food shoot, emptied thawed frozen mice and one bright yellow chick onto the hawk’s feeding platform. She left the food and stepped back, but the hawk didn’t move.

Corwin spoke behind her, soft, hesitant. “She likes voles. If you have any.”

Lynette felt his gaze on her but when she turned his eyes slid away. “We don’t,” she said carefully. “Laboratories don’t do wild voles. She’ll eat it, she did yesterday. I need to get back to work.” She eased away from the cage but he didn’t follow her. “If you’d like to stay,” Lynette said finally, answering the yearning in his eyes, “you can. But please keep your distance. She’s not used to humans. And we want to keep her that way.”

When Brad pulled up two hours later, Corwin, cross-legged on the ground, still hadn’t moved.

She saw Corwin every day after that. They came to a place without words. He meandered up the hill a few minutes after she drove up in Brad’s car and she’d nod at him and he would smile back. They came past that place and he began to tell her things, quick halting glimpses of the red-tail’s progress. She’d made it to the highest perch in the cage, he told her one day, and the day after that he said she’d caught a shrew that had dug its way under the mesh. Lynette had told this to Dr. Stein, and when Corwin came the next morning they’d moved the hawk to a bigger flight cage and the bandage was gone from her wing. Now Lynette threw live mice through the chute. The hawk’s feathers gleamed gold.

The day after the move Lynette caught the bus up the hill and told Corwin, surprising herself, that she’d left Brad for good.

Corwin didn’t say anything. She hadn’t expected him to. She sat with him a while, watching the hawk, and let his peace fill her to the brim.

She didn’t realize how close the end was. The next day Corwin told her the hawk should go free.

“Yes.” Dr. Stein placed one hand on her hip and watched the hawk move around the cage. She handed Lynette a towel and two thick welder’s gloves. “We’ll try and mug her quickly. Lynnette, remember to pin her wings.”

Corwin watched. His eyes on her weighed heavy, following each movement she made as she took his hawk, wild, untamed, into her hands.

The voice was the same, the same impotent screech, and that wild look in the eyes of no escape. Lynette closed her mind to the hawk’s desperation but she felt it anyway, the harsh accusing cries and the futile grip of talons on thick leather. The hawk would never know the human that shot her, but these monsters with the armored hands she would remember and hate, Lynette imagined, for the rest of her life. The hawk fought as they bundled her into the crate. Crouched panting inside, waited for her world to end. As careful as they were the crate lurched as they carried it, Lynette and Dr. Stein each taking a side. Corwin followed them like a shadow. They drove to the release site. Dr. Stein took the wheel and Corwin, in the back, held the crate as steady as he could.

They brought her to the release field and scanned the empty sky. It was good hunting ground. They’d released hawks here before. It was far away from guns.

Dr. Stein stepped back. Lynette handed Corwin the gloves.

But he didn’t take them. “You saved her,” he said, pressing them back into Lynette’s hands. “It’s your place.” She couldn’t read his voice, but it was her place, Corwin said, to give this hawk her freedom.

Lynette slipped the gloves on and opened the door.

They waited usually, spent minutes or hours assessing the new place they’d come to. This hawk paused one heartbeat before she staggered forward, spread her wings and flew. Sun caught on her feathers, late spring blowing with her on the wind. Fluid wing beats lifted her, up, and up.

Lynette never knew what made her look, how she knew then that Corwin would not be beside her. He’d come barefoot, but his jacket lay limp in the grass. Lynette lifted her eyes to the sky again and their hawk had spiraled higher, her feathers widespread and shaping the wind. The hawk was not alone. Two red-tails circled. Their shadows became one.

Lynette never saw Corwin again.