Through the Storm

Published on 2013-01-26

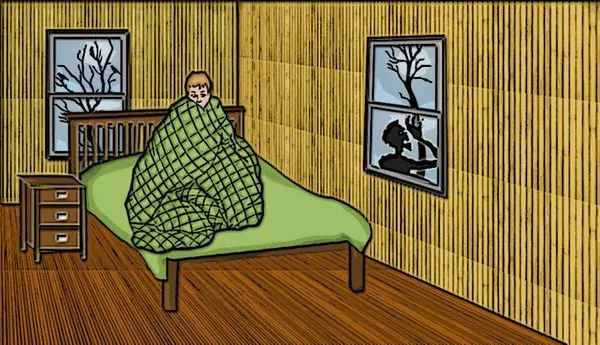

Just before sunset she smelled the coming rain and pedaled faster. Eleven kilometers more to the British camp at Lac du Nord; she was going to get wet. The officer had written the message on his camp table with a fountain pen on coarse paper which was the rough stock used to wrap candles in cases; if the message got wet it might become illegible so she stopped, rolled the message into a tube and shoved it into the open end of the bicycle’s handlebars.

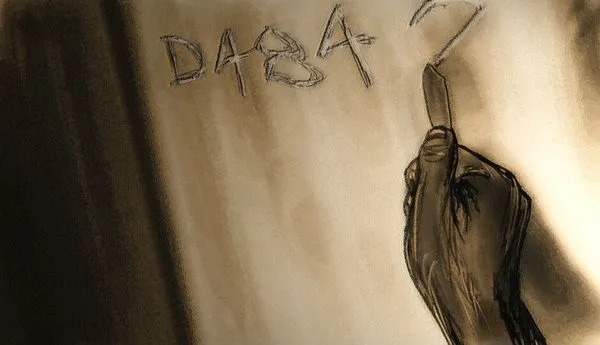

The first drops began falling. Splat spat, heavy drops. Yes, soon she would be soaked. The sky darkened quickly as the wind picked up. She wished she had borrowed her brother Daniel’s gloves but it was November and he was working all day outside with old Monsieur D’Arsette, the woodcutter, yes, he needed the gloves more than she. And at 16 he was three years older as well. She retied the scarf under her chin, blew into her cold hands then resumed pedaling toward the British camp. The rain pelted her right side and she worried that the open end of the handlebars might admit enough water to damage the document and again she stopped her forward motion. From her coat pocket she took the handkerchief and with it plugged the tube. Her fingers ached from the cold and she took a moment to warm them under her arms. Drops of rain dripped from her nose and chin. She dried her face with the sleeve of her cotton coat as best she could and resumed pedaling. The clay of the road was becoming softer and pedaling more difficult. Her back was thoroughly wet; her red coat was soaked through from the spray the back tire threw upon her. “This coat has never been so wet,” she thought, “what if the dye runs?” she wondered. The officer had given her 10 francs to deliver this message and said over and over again almost maniacally in his poor French, “tres important, tres, tres, important, cherie, comprendez-vous importante?” “Oui, Monsieur Capitain, très important’.” He promised that the officer to whom she delivered the message at Lac du Nord would pay her an additional 10 francs.

The wind picked up and shifted so that she was heading directly into the rain now mixed with sleet. Above the rain she could hear the rumble of thunder and see flashes of lightning ahead. She hoped it was indeed lightning and not artillery fire. The road narrowed now and began to climb. The last 3 kilometers would be uphill. She passed a farm with a large barn, considered the shelter it offered, then turned up the farm lane, but suddenly changed her mind as 2 large barking dogs bolted from the barn into the rain heading for her. She had to dismount to turn the bicycle around and had just remounted when she felt the teeth of the nearest dog bite into her heel. Despite the wind and the downpour she could smell the wet fur of the beast. Raising the injured heel she delivered a savage kick to the dog’s muzzle. Her shoe flew off as the black dog yelped and broke off the attack. The brown dog was now leery and quit his run to sniff the black dog’s injury. She pedaled furiously back onto the clay road heading back into the storm. The soft clay slowed the progress of the machine to slightly more than walking speed. The girl glanced at her shoeless right foot and saw the crimson stained stocking. “Maybe it’s just the red dye from my coat,” she now hoped, but no, clearly it was from the throbbing punctures of the dog’s bite. Her hair was soaked and clung to her forehead and cheeks. She had to brush the wet tresses from before her eyes every few seconds. She could feel standing water in her ears and she could feel the cold water running down her neck and back. Every centimeter of her body was drenched. The lightning was closer now and provided the only break in the darkness. A bright series of flashes illuminated a wooden sign on the road, “Lac du Nord 2km”.

After twenty more minutes she had to rest. She braced the bicycle against an oak tree and tried to warm her hands. The fingers were completely numb. Behind the tree she squatted to pee and placed her fingers beneath the warm stream. “Is this a sin?” she mused, “If so, I will not confess such a thing to Pere Jean. No, it cannot be a sin. Can it?” But the warmth to the fingers was comforting. 10 Minutes later she resumed the journey but the steep incline of the hill and the resistance of the soft clay mud made pedaling impossible. Now she pushed the bicycle through the mud, limping from the injured heel which throbbed with each beat of her heart. At the top of the hill the rain began to ease and she was able to coast on the bicycle to the foot of the last hill. Beyond that was Lac du Nord. But once again she had to push the bicycle up the soft clay track. At 11:30 she was halted by the sentry, then escorted to his captain’s tent.

“Monsieur, j’ai un message important d’un capitaine.” Her cold fingers could not manipulate the document from the bicycle’s handlebars but the British captain saw the effort and completed withdrawing the paper tube.

From: Capt.. Reginald Humphrey Stanhope, King’s Own Grenadiers, 2nd Infantry.

To: Capt. Barton Phillips, 103rd Artillery Company, Lac du Nord

“Barton, My entire unit, myself and all officers included, are down hard with this beastly Spanish Flu. We’ve lost three men already. Last shelling took out our wireless. I have employed this young lady to convey this message from Allied Headquarters. Please pay her 10 Francs. May God protect her and see her through to you. It’s over, old boy. The war is over. Here’s the text from headquarters received 30 minutes ago:

10 November 1918, 1755hrs

_ From Allied Supreme Headquarters_

To: All Allied Units

Subj: Armistice

A general armistice is agreed upon by the Axis and Allied powers. A cease fire is ordered to go into effect at 1100 hrs tomorrow 18 November 1918. Hostilities will cease at his hour. All allied units will respect this order. — Marshal Foch.”