The Kickball Game

Sara Jacobelli | Jordan Wester

Published on 2013-11-22

In our neighborhood, kickball was king. This was before video games, cable TV, home computers, iPhones, iPads, cell phones. We had TV but it was nothing but Divorce Court and soap operas in the daytime, what my grandmother called, her “Stories.” The good stuff was on at night, like Star Trek and Garrison’s Gorillas.

We played kickball in the side street, and we played all the time. All day in the summer, unless we got invited to the Tattaglia’s to swim in their pool. They were the only ones in our neighborhood who had a pool. It took up, literally, every inch of their back yard. You stepped from their back stoop and there you were, in the pool. Mr. Tattaglia supposedly made enough money in his construction business to move out of the neighborhood into one of the nearby suburbs, but the Tattaglias seemed content to stay here on the East Side, where they could lord it over the rest of us.

We played after school, too, and stayed out until the street lights came on. I was a good kicker, but my strong point was my running. I was a tomboy and could run faster than most boys, never mind the girls. Foster Square was the street we played on. There was no way we could play anything on busy East Main Street. On Foster Square the rules were simple; first base was a sewer grate, second base a metal garbage can lid, third base another sewer grate, and home plate another garbage can lid. You had to merely touch a base to claim it. You could either touch a kid when you caught the ball, or throw the ball at him or her to knock them out. If you broke a window you had to pay for it, while everyone else ran away screaming.

There were quite a few large Catholic families, so we usually had plenty of kids for both teams. If we were short and needed a kid, someone would even knock on the door and ask Danny Fritz to play.

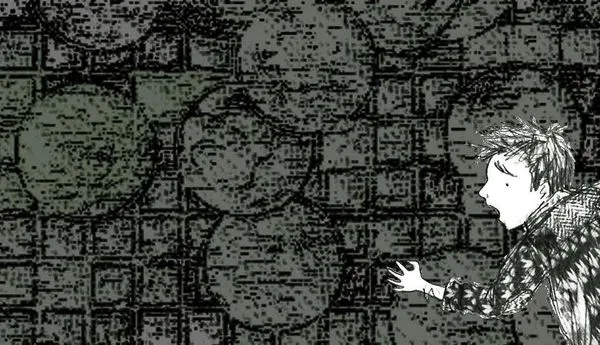

Red headed Danny was an Only Child. His parents were older, never went bowling or attended barbecues. They lived in one of the few one family houses on our block, at the very end of the dead end street. His mother never went to Tupperware parties, Bingo games at the Church Hall, or wedding or bridal showers. His father never went to Paolo’s bar on the corner, or joined in any poker games.

Danny was two years behind me in school. We all assumed he was spoiled because he didn’t have any brothers or sisters, and his mother dressed him in cute little matching outfits, which the other kids made fun of. “He looks like Little Lord Fauntleroy,” my mother said one time, as Danny’s mother walked him past our apartment building. Everyone else walked the twelve blocks to Beardsley School and back with a gaggle of friends. Danny was the only one escorted by his mother, who held his hand crossing the street. One drop of rain and his feet were shod in huge rubber boots while his mother held an umbrella over his head.

I told my friends the “Fauntleroy” name and it stuck. After that, everyone called him Fauntleroy. His mother’s name was Ethel and his father’s name was Herbert, which for some reason caused all of us to roll on the ground in hysterics. Danny’s bright red hair and painfully pale skin didn’t help matters any. He was weak and skinny and terrified that we’d make fun of him. Whichever team got stuck with Danny would insist on making a deal, such as two extra points for being handicapped by the weird kid.

One day we were short a kid, and it was my turn to go get Danny, the Extra Kid. By now, we all called him Fauntleroy. I banged loudly on the door.

“HEY, FAUNTLEROY! LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY!!!” I screeched.

“Go ahead, Danny. Go play with your friends,” Ethel Fritz said, gently pushing him out the door. He looked so scared I thought he was going to pee his pants.

“You guys want me today?” he whispered.

“Yeah, come on!” I grabbed him roughly. Then I thought of something.

“You think your mom would give us some snacks?” Danny didn’t say anything, but Old Ethel Fritz heard that one, and she shuffled inside. I dragged him down the street to the game.

“Listen, kid,” I lowered my voice. “Everyone here’ll be nicer to you if your Mom gives us some snacks and drinks.”

His pale face turned red and his nose started to run. “OK. She will, I know she will.”

It was my turn to kick, and I forgot about Danny. I kicked the ball hard and it went flying down the street. Greg Riccio clambered after it, and I smoothly made it to second base.

Our team won. Danny was on the other team and was useless, as usual. He went back in his house to go to the bathroom three times. He couldn’t throw, catch, kick, or run. He didn’t even try to defend himself when anyone made fun of him. He just hung his head and sniffled softly. We didn’t feel sorry for him. He was just there.

Old Ethel Fritz came through with our snacks. She even set up a little card table. She brought out a pitcher of grape Kool-Aid, and a stack of plastic smelling red and blue cups. She piled a plate high with Oreos. She even included napkins, though none of the kids bothered to take one.

“Hey, are you ‘dopted’?” Tina Tattaglia asked, her mouth full of Oreos. At thirteen, she was the oldest kickball player. She kicked, threw, and ran like a girl. But everyone had to be nice to the Tattaglias, because summer was coming and they had that inviting pool.

“No.” Danny hung his head and took a tiny bite of an Oreo. I noticed that his skin was so pale, you could see his blue veins protruding.

“What’s ‘dopted” mean?” Kevin Ruggerio asked. He bounced the kickball rhythmically against the stoop.

“It means,” I said, “that your parents aren’t your real parents. Your real parents didn’t want you, and they gave you away.”

Danny started crying.

“Well,” I added. “Your parents are really, really old, so they probably couldn’t make a baby.”

Everyone laughed. “Yuck, Ethel and Herbert DOING IT! That’s gross, Carmen,” Greg said.

Danny looked at all the laughing kids. He ran back home as fast as he could.

“Wow! Look at him go!” Tina said, gulping some Kool-Aid.

“Yeah,” I added. “My team’s lucky he didn’t run that fast when he was playing.”

That got a few laughs. Kevin swiped some cigarettes from his mother, and we hung out on the Riccio’s stoop, smoking, until the street lights came on.

***

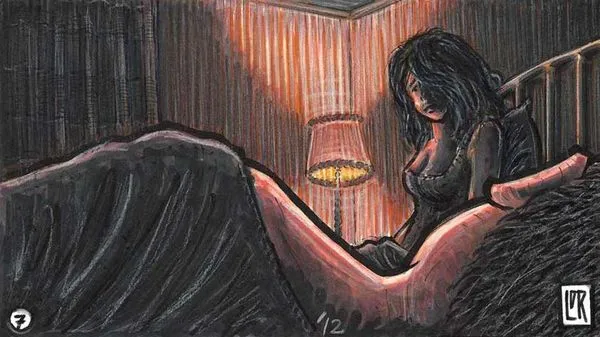

I didn’t see Danny much after that. He was two grades lower than me and he was absent a lot. Then my mother came home from work with a bit of gossip.

“Mrs. Fritz came in today. She said her son has been sick, in and out of the hospital.”

“Oh, no, Fauntleroy is sick. He probably has a cold and she brings him to the hospital.” I laughed. My younger brothers and sister joined in, chanting, “Fauntleroy! Fauntleroy!”

“Well, it sounds like it’s more serious than that.” My mother lit a Lucky Strike. She sat at the kitchen table reading the classified ads in the newspaper. “But, we have our own troubles. If they close the cleaners, I’ll need a new job.”

“”I’m gonna knock on Danny’s door to see how he is,” I said, running out the back door.

“Carmen, just leave them alone,” my mother said, absent mindedly.

No one answered the Fritz’s door anyway.

***

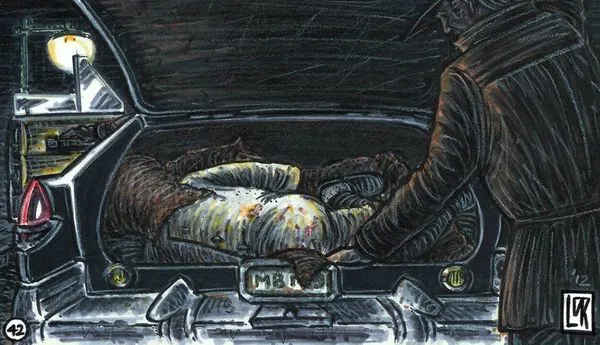

A few months later, my mother showed me the obituary in the Bridgeport Post. I read it out loud: “Daniel Joseph Fritz, age eleven, died of childhood leukemia early Saturday morning, after battling the disease for two years. He is survived by his parents, Herbert and Ethel (Gunther) Fritz. Services will be held at the German Lutheran Church on Boston Avenue.”

“Hmmm,” my mother said, sipping her coffee. “German. No wonder they never fit in.”

“What’s wrong with being German?” I asked.

“Nothing. It’s just that, well, everyone around here is Italian. Or Irish. Or even Polish.”

“I didn’t know he was eleven, like me. I mean, he was only in fourth grade, and he was so scrawny.”

“He probably missed a lot of school, being so sickly. Thank God you kids are all so healthy. Healthy as horses.”

“I’m gonna go play kickball,” I said as I ran out the door. Before I joined the game, I ran to the end of the street to look at Danny’s house. It looked empty. A bright red and white “For Sale” sign was planted in the neat front lawn.