Mud Boy

Published on 2014-03-14

Mud Boy splashed through the puddles and sloshed through the mud, then launched himself onto the soggy turf. The field was so rutted from dog play that he didn’t slide but stuck in place—his face submerged in two inches of water, his loins in cold mud. Mud Boy’s mother laughed nervously, for people were watching. Mud Boy smiled up with a wet clump of grass sticking out of his mouth. His mom smiled down at him. “You look like those dinos eating in our book.”

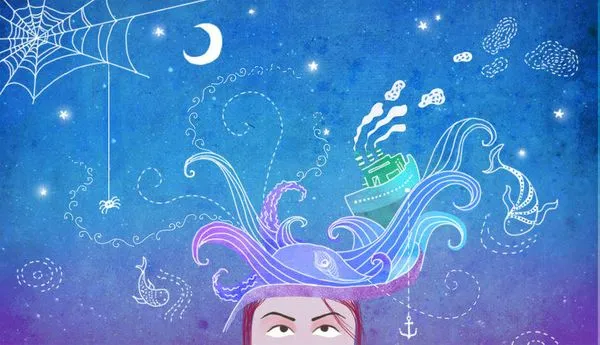

“Brachiosaurs!” said Mud Boy. He chomped on the grass and decided to like it. Energized by the boost, he thrashed his limbs as he did when he swam, and Marina leapt nimbly back from the splashes. Mud Boy rolled over and stretched out his limbs, then sloshed about to imprint a mud angel. He howled up at the charcoal—gray sky. That brought curious dogs that barked and pranced and poked at the boy. Mud Boy leapt to his feet and thrust dripping arms skyward: “Let the wild rumpus begin!”

“Don’t ever change,” murmured Marina, unable to distinguish her tears from the raindrops that clung to her cheek.

Blood Boy loved knives of all kinds, and scissors, razors, scalpels, and pins. When Marina sent him to school with an exemption from frog dissection, he shredded the note with scissors, then smuggled a frog home and dissected it with a stolen scalpel. “These are its guts,” he told Mud Boy. The scientific tone of his voice was contrasted by the gleam in his eyes as he scrutinized Mud Boy’s face. “Go ahead and scream, Mama’s darling.” Mud Boy looked down at the tiny string of intestines suspended from Blood Boy’s thumb and forefinger like the sausages on the wall at Gladkov’s deli. Blood Boy saw his three—years—younger brother’s lips quiver, and his hand twitched the scalpel. “Papa hates cry babies,” he said, and Mud Boy swallowed hard and replied: “Papa’s … not … here anymore.” Blood Boy ground his teeth. “Thanks to you.”

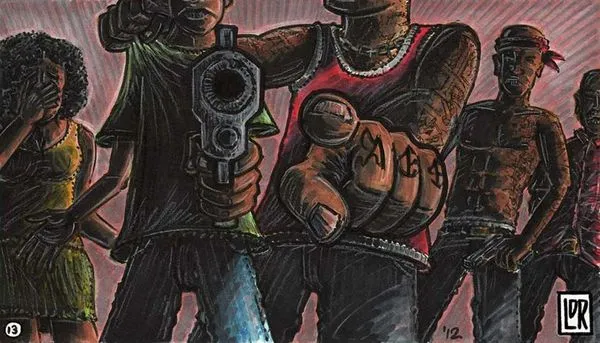

Blood Boy got Grand Theft Auto, a skateboard and spray paint and three secret piercings. Mud Boy got stuffed animals, art supplies, private art lessons, and, at thirteen, a big fluffy dog that he cuddled for hours. Blood Boy got cocaine and a razor blade and urged his brother: “Join me, Sergei. Show us what you’re made of.” His friend Dmitri sneered: “He’s made of mud. There’s mud in his pants.” Blood Boy’s steely gaze willed his brother to comply while defying him to show disapproval. Mud Boy looked helplessly at the rafters and a gang of little black spiders. Blood Boy chopped the cocaine into lines and inhaled fiercely.

Blood Boy got graduation thousands from his absent dad and thousands more from his mom, who could scarcely afford it. He bought a black Civic and muscled it up for street racing. “Serge,” he said in a plaintive voice. “Let’s go for a ride, man. My car is so cool.” Serge sat on the couch wedged between his mother and Poppins, the big yellow Lab. He gave a jerk as if to rise, but Marina squeezed tighter. “Grigor,” she said in a voice more tender than it had been in years. “You’ve got a car and a full tank of gas. You’ve got money too, and you’re handsome and bold! The world is your oyster.”

Marina and Grigor locked eyes from across the room. How tall he was, how lean and strong—and his wolf—gray eyes were so like his father’s! Grigor gazed at his mother, so lovely and sad, yet peaceful somehow. Her face was weathered, and there were many more gray strands in her hair—and all of them his, she had so often joked. And not joked, too.

“Be free now,” he said, and flew from the house.