He Eats Sparrows

Published on 2014-12-11

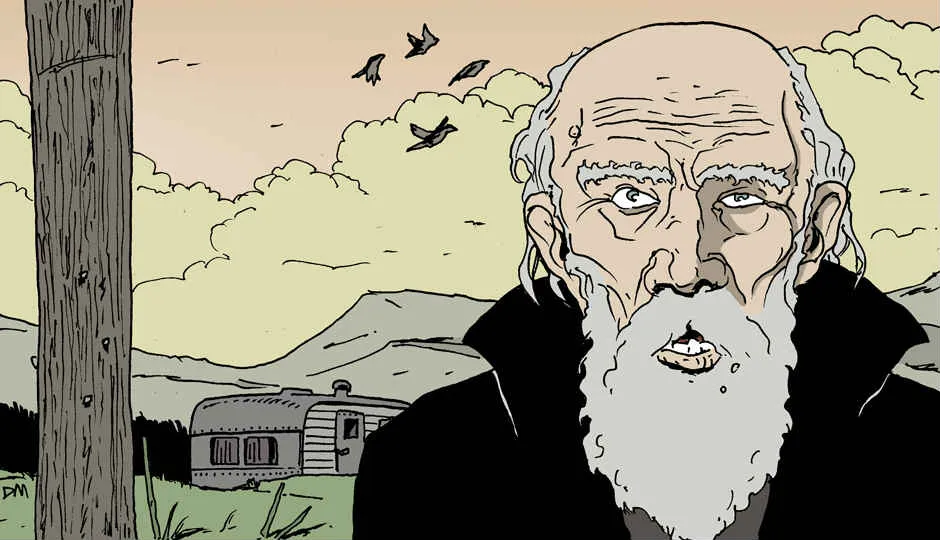

He eats sparrows. He positions himself between the wall to the mobile home park and the hawthorns and stays quiet, motionless. Then his hand goes from thigh to knee, rises from his jeans, and snatches. He’ll eat three or four, says there’s not much meat on a sparrow but after the feathers and the beak, everything is edible, though I never listen to exactly what it is that is edible. He grew up snatching birds in London, used to stand near chimneys in winter and snatch all types of birds, his face and hands covered in soot depending on the age of the house. When I first heard him called the Birdman, I thought it was his slender figure, his almost emaciated appearance that brought on that epitaph. He had immigrated to Baltimore with his mother, and after she fell ill and needed warmer winters, emigrated to Capitola, California. Birdman spoke about her work as a tailor but never mentioned that he, Bill, had not worked a day in his life. His neighbors suggested that he lived off his mother’s disability check.

I like him, liked his stories of pre-James Bond England, pre-Mary Poppins.

He said in London the days and nights were dark and grim, but World War II had exhausted the people for so many years they loved the ordinary and raised dreariness to an art form. The intellectuals wanted spastic electricity, but the populace wanted everything smooth, beer, speech, rivers, life.

We play dominos some nights outside his mobile home on a little table he sets out and takes back in. When the light leaves the sky and you have to touch the dimples in the domino to know a six from a three, play ends, he retires to his mobile home. I have never seen him turn on a light, assume he lives in the dark for seventeen hours in the winter.

We play backgammon less often, which is his favorite game. The way he snaps up the die so quickly reminds me of his bird-snatching aptitude, and that he chuckles after every swipe chills me.

Recently he has taken up with telephone poles, climbing them, removing the odd hundred staples left in them from people posting about lost cats, dogs, yard sales, moving sales, balloons for directions and red cups for parties. People think he’s become a sort of harmless peeping Tom from his position ten or twelve feet up a pole, and some joke it’s brains of the sparrows taking over his brain. He laughs.

I wonder.

His left hand has withered over the last year. He cannot hold a pen or newspaper with it, has to eat his morning porridge with the bowl on the table instead of cupped in his left hand and the large spoon scooping a short distance through the timbers of his beard to his slurping lips. Now he bends over his bowl like a man who has been imprisoned all his life. The slurping has stayed the same.

Yesterday we saw a physical doctor who shook his head negatively over much of what he saw and found by probing Bill’s body. Bill tittered every time he was touched, and I wondered how many years it had been since another person’s hands had touched his flesh, with the answer quite probably when he was a child and his mother had bathed him. Sixty years without a human touch.

I peeked inside the medical pouch. The doctor had circled a few items for the surgeon—the “bruise” on his wrist needed a biopsy to check for dying tissue—he feared gangrene. The hand and wrist had little circulation, and the nerve that wound through the shoulder and skirted through the elbow had irreparable damage. At some point, both in time and position, Bill would lose his arm. “Withering,” the doctor wrote, “withering arm, withering legs, withering face—malnutrition for many years.”

Bill wanted to read it. He took it out of the pouch as we neared the medical center, scanned it with considerable speed, and laughed. “Sounds like I’m gonna die.”

I nodded. “Doesn’t look good.”

“Just as well,” he said. “Not many birds left. I feel pretty alone. I’m tired of climbing the poles, too. Not much to see either. It’s like London back in the fifties all over again.”

I looked at him. He looked hungry, he always looked hungry. “You want to get something to eat afterward?”

“Sure,” he smiled. “I’d love some pie.”

“What kind of pie do you like?” He didn’t answer. “Apple? Berry? Chocolate?”

“Nope. The kind of pie I like’s not in any restaurant,” he said, then sneered. “Blackbird.”