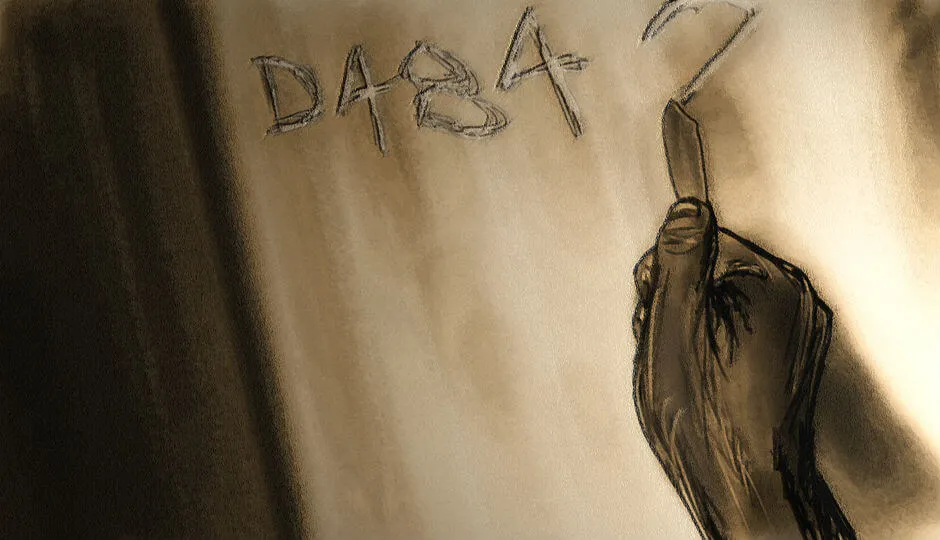

D-4842

Published on 2017-01-25

C-1192 chose to do the things he did, he gets no sympathy from us, they say.

C-1192 played baseball, I tell them, and neighborhood kids would wait and watch the roughly bound leather balls soaring over the prison gates, catch them and take them inside and hide them in shoe boxes under the bed. They say- how many people did he kill with a bat?

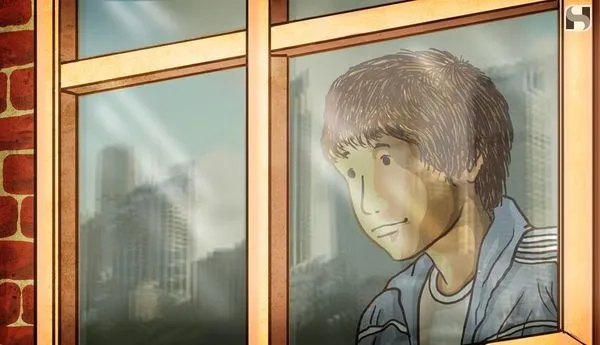

Martin sprawls his books out on the table in front of him, he is studying for an electrical engineering exam. There are numbers and letters configured in rows, plus and minus signs and parentheses between. The book is called Calculus is Sexy and features a thin woman with bleached hair and thick square glasses on its cover. He is quiet, always studying. His laugh is gentle, never out of place. He pretends not be listening, but always is, the conversation around him loud and heavy. His smile is subdued, he pencils in fractions in a spiral notebook.

Each morning, C-1192 would dress in a cotton shirt and slacks and play with the dial on his radio. I tell them: He liked to listen to doo-wop, the airy notes pushed through static like raw meat through a grinder. He ate breakfast in silence.

They allowed him a radio? They ask. So what, I bet he had his caviar delivered right to his cell too?

Martin chose to do the things he did, he gets no sympathy from us, they say.

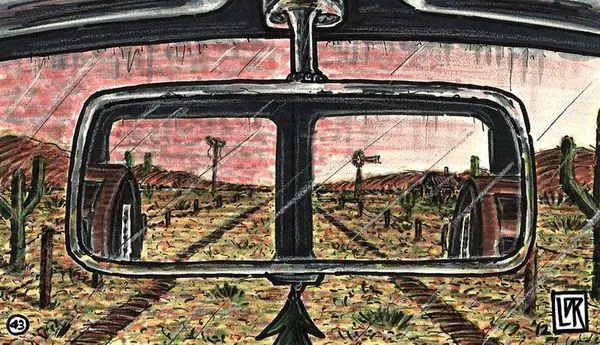

He chose to sell the drugs: carried them across state lines, wrapped in plastic, taped inside the inner lining of a suitcase, stacked in the trunk of a 1991 Ford Taurus in rusted blue. He was at home when they came, knocking brusquely on his door, waving a white piece of paper. They knew the names of people he had worked with, they tackled his brother to the ground, left Martin shouting “wait, it’s me it’s me”.

They led him outside in handcuffs, his brother face down on the tile, an hour passed he felt the strength to stand up.

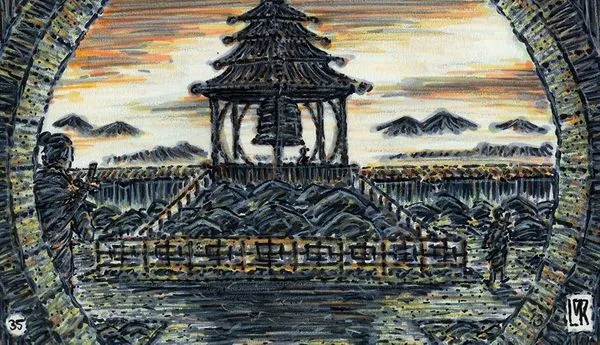

While C-1192 ate breakfast, someone replaced his bed with a bunk bed, I say. A boy called D-4842- no more than sixteen- was sleeping on the bottom bunk. They stood together in silence. The radio was gone.

That all happened here, I say. They say: would you mind taking our picture?

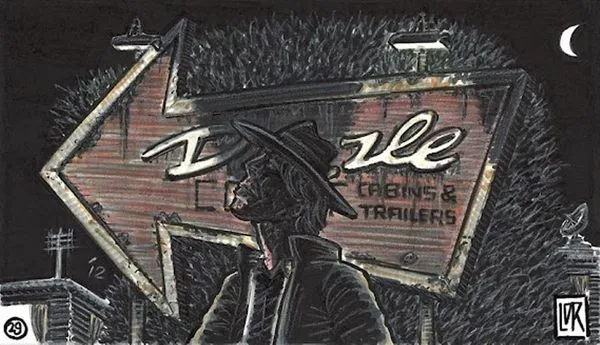

Martin found the cellphone- an old model which could flip open and closed- in a Ziploc bag, stuffed with napkins and stored inside a hollowed-out copy of All Quiet on the Western Front. He stared at it for a long while, and recited his brother’s number in his head.

The boy, D-4842, was found to have a sharpened butter knife in his waistband, I tell them. They sent him underground to be punished. We walk down the stairs, I open the gate. Rainwater drips from the pipes.

They tell their children, “be good or this is where you end up,” and the children say “I don’t understand.”

“This is where bad people go,” they respond.

They found the cellphone burrowed inside the yellow foam of Martin’s mattress. Only one number was listed under Outgoing Calls, though the officer dutifully scrolled through every call- each labeled with a red ‘x’ to show the call had not been picked up.

When D-4842 was finally taken back into his cell, he held up an arm in front of his eyes to block out the light. He lay across the bottom bunk and wept, I say. C-1192, trying to drown out the noise, hummed an old doo-wop melody he remembered. I hum it, too. Blue Moon, you saw me standing alone, without a dream in my heart, without a love of my own.

They walked Martin from his cell, across the grounds. There was going to be a hearing, they told him. You never know what someone could do with a cellphone behind bars, they tell him. Scary things, they say. Dangerous things.

They say, “my, this place is so terrible. Certainly some prisoners would hurt themselves?” They seem eager. I say, sure. D-4842 wound his bedsheets tightly into a thick rope and threaded them around a piece of piping that jutted from the ceiling. He hung and hung and finally died, dreaming about a game he used to play, racing sticks under stone bridges. A child disappears inside of a cell. “Can I lock them in there?” the parents laugh.

The hearing took ninety days, and he stayed alone inside a cell that smelled like plastic but was covered in metal. He rolled up his mattress when they came to the door. You can put that back down, they told him. We have no way of knowing what you were going to use that phone for, they said. Some time away should help, they said and shut the door.

“I want to see the electric chair,” a child says.

They didn’t kill people here like that, I tell them.

“How do they kill people today?” they ask.

Sometimes they throw stones, I say. Sometimes they let them hang from a rope. Sometimes they shoot them in the back of the neck.

“Thanks,” they say. Their parent asks: is there anywhere good to get a bite to eat around here?

They did not open the door for a year. Martin scribbled in the back of books. A woman brought him food and looked through the slot. She asked if there are any books he would like her to bring. He tries to remember titles from school. He tries to remember that there were once bookstores, with rows and rows of open shelves.

C-1192 scratches a D 4 8 4 and 2 into the corner of his cell with a butter knife.

“What’s that?” they point.

I don’t know, I tell them. It’s probably nothing.