The Lion of Abilene

Erich Earl Forschler | Alberta Torres

Published on 2013-08-20

As seen from the balcony the ocean was every bit a living, breathing thing. The rain created a haze above the land that stretched out beyond the beach and over the ocean, eventually swallowing the living, breathing thing into an indiscernible grey smear. The beach was empty of people or birds. The weather had reduced the beach to little more than a smooth and wet welcome mat for the ocean, should it ever decide to leave the ambiguous grey and venture further inland.

I sat on that balcony and watched the sky eat the ocean which ate the land and smoked cigarettes and drank coffee with a man named Applewhite. Ed Applewhite was in his mid-sixties then, and had we known each other earlier I might have had a different impression of him than what I have now. He sat across from me in the other plastic patio chair, looking out at the water with a flared nostril frown frozen on his wide, wrinkled face. I viewed his perpetual disdain for everything he saw as a product of age and circumstance rather than a condition of his general character. My partner did not share my tolerant attitude.

“Weather sucks,” I said, projecting my estimation of Ed’s demeanor into words. He glanced at me with the look of a man who was working through a mental problem until he had been rudely disturbed by a stupid comment. Then he looked back at the ocean. It was clear to me that Ed Applewhite was a man trapped — trapped like the ocean before him, roiling, vibrant, ambitious, yet trapped in a bland veneer with the only options being to either ebb or flow. For the “Lion of Abilene,” the circumstances were likely a few degrees shy of becoming purgatory.

“Well it figures,” he eventually said, presumably to me, but more likely directed out to the ocean — to no one.

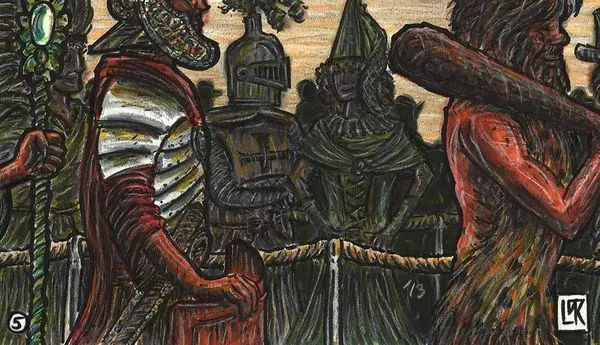

Ed Applewhite was once a champion, Gold Glove boxer from Abilene, Texas. His manager dubbed him the “Lion of Abilene” early in his career because of his tenacity and resilience in the boxing ring. Now, “The Lion” never really made it big in the boxing world, but he remains a local legend because of the way he fought. Ed Applewhite, while he had lost his share of fights, had never been knocked out. Never.

Then, in the fading days of his career, Ed fell into debt and vice and other problems that tend to haunt men when they face oblivion. Over the next twenty or so years, Ed established himself as a very productive criminal, and by the time we had met each other he was an old grandfather with too many ghosts and too little time. He decided to retire a rat. It crippled him visibly, and I could see him age by the day as we hid in a beachside condominium on the Georgia coast for a few days in February.

As I am still employed in the same manner I was when these events transpired I am reluctant to divulge the exact nature and details of what exactly I do, or from whom my salary is delivered. For the sake of this story, it should be enough to allow that I protect people who need protection, in public and open places made secret and hidden through use of aliases and other deceptive means. At the time of the coffee and balcony sitting my partner and I were waiting for a phone call which would tell us whether or not Ed Applewhite had earned more protection or something else.

I always preferred the “more protection” side of my work. My partner had a penchant for the latter. The “something else” calls were rare, but they did occur, and because they happened at all it was necessary that our team consist of men with different skills and abilities. His name was German in origin, but everyone called him “Bud.” It was not a term of endearment, however. He simply went by “Bud.”

Then Ed turned to me and said, “How long we gonna set here like this?”

“As I explained earlier, we’re wait—”

“Don’t give me that shit,” he said as he waved an angry hand and looked back at the ocean. “I know you know, so just tell me.”

“Well the truth is that I don’t know.”

“Look, fella,” he said, looking at me and leaning forward in his chair. “I ain’t goin’ nowhere, so just stop with all this whisper shit.” Per my instructions, Ed wore dark sunglasses whenever he went outside, even if it was to sit on the balcony. But even through the tinted lenses I could see his blue eyes flare with a violence and seriousness I would never fully understand.

I steadied myself against his gaze and said, “I’m not sure what ‘whisper shit’ means, but the truth is that I’ve told you everything I know.” Ed leaned back into the chair and shook his head. “These things usually move quickly,” I continued, “but you must understand the time it takes to gather the necessary resources, personnel — how long it takes to plan such things—”

“Give me a break, guy. You people got some pretty specific shit outta me. It don’t take this fuckin’ long.”

“There’s a lot of moving parts,” I said.

He scoffed at that and said, “Moving parts… all y’all say the same shit, you know that?”

It was clear that he was finished talking with me then. I was useless to him at the moment. We sat on the balcony and listened to the wind and rain and waves, and I drank coffee and smoked cigarettes while Ed Applewhite sat and stared.

We sat like that until he said, “All this hidin’. I feel like a fuckin’ rabbit.”

From inside the room, where Bud relaxed on the couch and watched television, I heard a voice muse, “The rabbit of Abilene.” Ed said nothing.

On the third night there, Ed and Bud nearly came to blows when the former woke to find the latter sitting in his room and watching him as he slept. The two of them had previously discussed their prowess in surviving life in a dangerous world. Ed boasted of his ability to sleep lightly and wake without the usual grogginess that beset average men. Bud then boasted in return, leveling a charge that he could sneak upon, and subsequently haunt, the dreams of any man. It was like that between the two of them, and I was stuck between it.

It really started on the first day, when we retrieved Ed from one secured location and transported him to the coast. The first thing he said to me, as he pointed to the shoulder-holstered pistol behind my jacket, was, “You ever shot anybody with that thing?” I told him the truth. He rolled his eyes and shook his head. Then he and Bud stared at each other for a bit before Ed nodded and told him, “I reckon I already know your answer.” Bud’s chin lifted at that comment.

We passed the days there playing cards and sleeping and otherwise managing the tedious silence and awkward air between opposing forces. Ideally, Bud and I would take turns between sleeping and providing security for Ed. However, as was usual for my partnership with Bud, I spent the time protecting while Bud did whatever he wanted to do.

“You like babysitting, so you babysit,” he said.

“It’s not like that and you know it,” I replied.

“Well you do what you need to do, and stay the hell out of my way.”

“This is our job, Bud.”

“Yeah, well you’re better at some things and I’m better at others, so let’s just keep it that way.”

I had no choice in the matter. Bud was convinced that we had nothing to worry about as far as protecting Ed. Rather, his primary concern was Ed himself. Bud believed that Ed was a liar, and he convinced himself that Ed would turn on us the moment he could. I did not share his skepticism.

On the second day I found Ed staring wistfully at a photograph he kept concealed in his wallet. The picture was of a little girl, perhaps five or six years old, laughing with outstretched arms at someone or something unseen behind the camera. He promptly hid the photograph the moment he realized I was watching him, and then he cursed me for being “a goddamn sneak.” On the fourth day he confided in me that the girl in the picture was his granddaughter, and he proudly claimed that, “This is what it’s all about right here.” Then he disappeared later that night.

I know why he did it. Well, at least I think I know why. The men he was betraying would surely use anything they could to leverage their vengeance against him, up to and including family members. When several days passed without any word as to the success or failure of operations born from the information provided to us by Ed, I saw the man lose hope that his family would remain unharmed. Not that he would openly admit to any of these considerations, of course.

So on the fourth night I woke suddenly when I heard a commotion outside. There was a loud thud followed by more strange and abrupt rustling sounds. I sat up and listened, hearing only the distant waves breaking through my open bedroom window. Then the rustling returned, and the distinct clink and snare-like ratcheting of handcuffs. Suddenly the floor was beneath my feet as I threw off the sheets and stood. I turned on the bedside lamp and reached under my pillow for the pistol. Then I listened some more as the ocean seized and rolled, crashed and receded. The wind outside played lightly with the curtain, teasing it silently.

Then I heard the shouting. It was Bud’s voice, and it was panicked. “Hey! Hey!” he kept shouting from the balcony. Then I heard the door slam shut, followed by the muffled sound of footsteps moving away down the hall. I ran to the balcony and found Bud hanging from the railing, his hands cuffed together with the chain around the bars. His feet kicked in the darkness, forty feet above the concrete below. He held the bars with his hands.

“Go get him, dammit!” Bud shouted when he saw me on the balcony. One eye was swollen shut.

“What hap—”

“Just go!” he shouted.

I left him there and exited the room, running down the hallway and losing myself, morphing into a pistol-wielding hunter in pajamas in the peach wallpapered, tan carpeted tunnel with subdued yellow lighting. Ed’s image flashed through the darkness outside as I reached an opening in the hallway near the stairs leading down to the parking lot. It was only a brief glimpse of a white-haired, weathered body sprinting from the light and into the shadows below. I followed him down the stairs, jumping several steps at a time, riding the echoes of bare feet slapping cool concrete.

The wind was heavy outside, shaking the palms that lined the parking lot and standing me up straight the moment I emerged from the stairwell. Ed was not at the bottom of the stairs, and I did not see him in the darkened parking lot, either. I stepped out into the parking lot and looked up to see Bud’s legs kicking and flailing above and a few units down. He shouted something at me, but all I understood was the word “beach.” I made my way toward the ocean, and as I rounded the building I could see the shape of a man fade from the boardwalk and behind the dunes around it. I sprinted after him, tearing a hole in my toe as I ran too quickly and carelessly over the boardwalk which held several half-committed nails in its splintering, uneven boards.

I crested the dunes to view the beach and crashing waves before me in the darkness. The water sounded closer than it was, and it was visible only as an occasionally reflective black void that rose and fell against the intermittent lights from boats and oil derricks on the horizon. The sky was still clouded over though the rain had ceased. Still, the presence of the clouds made the entire beach dark. I searched the beating winds for movements in the night, and after several passes I finally glimpsed something in the water, nearly fifty feet out from shore. There, bounding in the black fluid was a mass of floating white hair, tracing a straight and steady line away from me. He was swimming away.

I waded into the surf, losing and regaining my balance against each freezing and salty blow to my legs. The dark water thrashed and rolled as I shouted out into the abyss where the white speck disappeared into the surrounding rise and fall of shadow. The few lights on the horizon held, slowly warming and fading in what felt like a cruel apathy to my calls. And soon I was sitting on the beach, with my arms resting atop bent knees and my hands dangling a pistol between them, watching the dark water and waiting for it to bring something back. I waited, hoping that the image of white hair — the mane of a lion — would reappear against the dark fluid curtain.

But it never came back.