Absolute Zero

Published on 2013-05-29

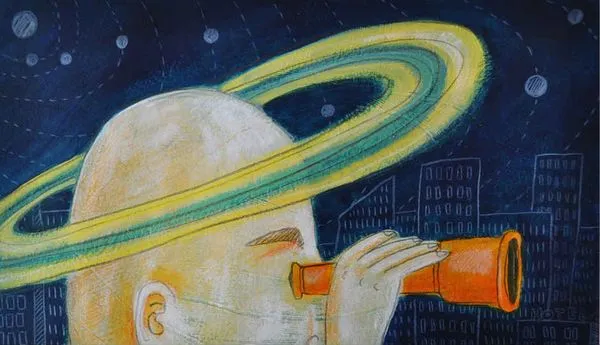

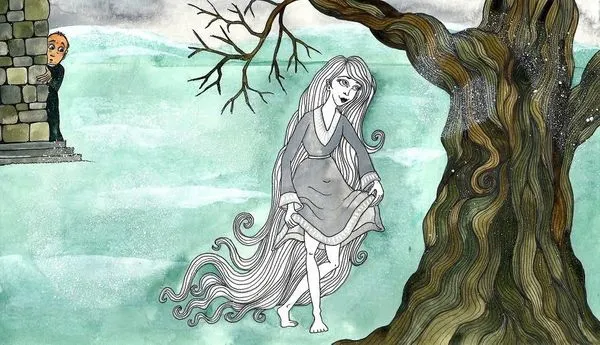

Out on the hill under the blazing red maple is where he left his bag. The seeing man waited until that moment in autumn occurred when all the leaves flittered and danced and received notice to come alive—or whatever it was that happened in the universe, or the moon phases, or the shortening of days. He waited, I think, because he knew I would see the red tree. And that I would go there.

His spot, his special spot, was under the canopy of the biggest tree on the hill. He had that bag, that duffel, with him when he arrived. The first time I saw it, it was no more than a weathered leather strap peeking out from under the velvet covers of his stall. He kicked it aside when he noticed my glance. I knew it didn’t contain any tricks of his trade, that it probably held little more than toothpaste and a razor. But he didn’t shave, did he? Maybe, then, there was no razor. Maybe toothpaste and a pair of patterned socks. Maybe nothing at all, for to leave with nothing is to run away; to leave with a bag is to fly away. But nobody else knew. And that’s why he let the strap peek out from under the cover of his stall. He knew I’d be looking.

The older ladies thought he was charming. They called him a nice young man but he wasn’t young. They couldn’t know that the costume he wore was his only one. Even then I didn’t think the duffel bag contained another set of clothes.

They called him exotic but he had never traveled by plane or crossed an ocean. And his bare feet—how they loved to ponder his connection to the universe when he removed his shoes and buried his toes in the earth. But I’d seen the lolling tongue of his broken shoes peeking out from under the stall. Next to his bag. Kicked aside that first time, when I’d been caught looking.

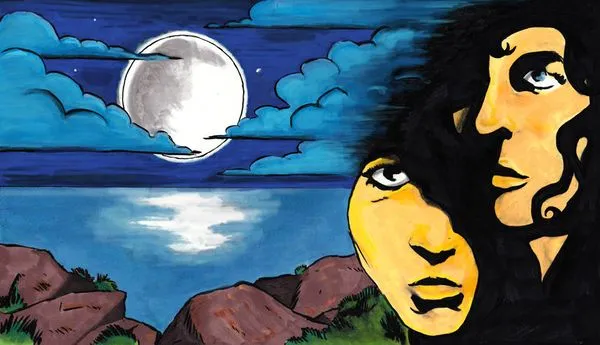

And so I’d given him my palm. He’d looked me in the eye and told me, without words, to take his hand but not fall for the joke. He held my hand in his, studied it, and closed his eyes. He squeezed it once. He opened his eyes and smiled. The ladies, of course, had gathered around to hear what he would say. Not that they cared for me; they’d tired of my antics long ago. And so he told them—me—little things. Little things he couldn’t possibly know, but did. And they laughed. And applauded. And I cried, but not with unhappy tears. They were silly, childish tears of knowing the joke wasn’t quite a joke after all. I froze, as if the earth’s core had frozen too, and every living cell in my body ceased to exist in a funny, fleeting instant of absolute zero.

When they moved on to the other stalls, he leaned in. Then he told me other things. Things about the ladies. Things about the men. Things about the children at school and, finally, more things about me. But I already knew these things. He laughed when I couldn’t speak. “Don’t worry, little bird,” he’d said. “Everybody special has to fly sometime.”

“But I don’t have any wings,” I’d whispered.

“Yes you do,” he’d said. “I see them.”

Other stallholders came and went and the seeing man with the one costume and the broken shoes, the man who didn’t shave and owned nothing more than one tube of toothpaste and one pair of socks, remained. The ladies said surely he should leave too. Surely he should ply his trade elsewhere. Their painted lips and pretty smiles welcomed him again next year to take their hands and tell them their deepest secrets. They laughed. Because they weren’t really their secrets. Not really. And the man smiled too, and said thank you he’d be delighted to see them again. I know because I was there and I reached for his bag, for the strap only I knew about, but he’d stopped me. He’d put his hand on mine then and said, “The skies aren’t right.”

The men didn’t much like him. To see them in their best suits, scratchy and tight through the shoulders, place their sweaty hands in his while he leaned in and whispered to them made me laugh. Not the childish laughter of knowing the secret of the joke or the ridiculousness of their discomfort, but the awkward laughter that comes when you see a cheek flush red and sweat form at the temples. Or a hand pulled away from another’s.

Their wives would come looking for them. They’d have freshly baked cakes or carnival food in their arms. Look what I’ve brought you, they’d say, and the men would jump up and away from the stall. They’d smile at their wives and the wives would smile back and everyone would smile at the man. But it was time to move on, wasn’t it? The other stallholders moved on to another place, another town. Other people, surely, deserved the treat of the man’s show. But the skies weren’t right and it wasn’t time to fly.

And then, as the summer ended, the carnival was gone.

But the man wasn’t gone. His stall was up on the hill under the blazing red maple. He sat there every day waiting for a palm. But I knew he didn’t need a palm to see; he didn’t need the show to see.

The days shortened and the rain fell sometimes. The air was cold and the earth was too hard for burying toes. The birds all disappeared as the winds grew fierce and the only thing left was the blazing red maple.

Isn’t it now time to leave? everyone wondered. The men took the ladies’ hands in theirs. It was all just a joke, but even jokes have to end. I know, because I was there. The man looked at me and said without speaking, “The skies are right, little bird.”

“But I don’t have wings.”

“You do. I can see them. And I think you can too.”

The men let go of their wives’ hands. Told them to go home. They spoke with the man and thanked him, once again, for his shows. His jokes were no longer funny, and it was time to move on.

He left the bag on the hill under the blazing red maple.

And so, passing the school and the offices full of starched collars and the shoe shops of high heels, I set off.

It takes thought to begin flight; an idea, which leads to an electrical impulse, which leads to a muscle spasm.

I thought hard. I raised my arms, but having never raised my arms, the feeling of uncertainty and fear, and a ticklish niggle as feathers rearranged, occurred to me. It lasted no longer than a carnival reading, no longer than a funny, fleeting instant. But the tickle settled. I stretched my arms. I bent my knees, pushed off, and took to the sky.

I left my shoes under the blazing red maple.