Three Uninvited Guests

Nels Hanson | Péter János Novák

Published on 2013-03-23

In my father’s house, the day I came of age to join the older girls who walked in the meadow among the young men, my mother told me a story her mother told her, that her mother heard from her mother, who heard it from hers, the changeless tale told by all mothers that tomorrow I must tell my own daughter, the story that’s called “Three Uninvited Guests.”

In the beginning, my mother explained, it was Zeus in disguise, the white bull charging from the sea, who took the woman named Europa on his strong back across the ocean to Crete, where he had her worshipped as the goddess Hellowtis, after she bore King Minos and his brothers.

Blue Poseidon then gave the eldest son of Zeus a wonderful bull for sacrifice, a dazzling milky animal swimming in the surf, like the foam-white bull that had loved his mother, Europa. Minos was impious and greedy and at the altar, at his clever counselor’s advice, he offered a black bull dyed white, sparing the god’s pure gift to breed his royal herd and strengthen its blood.

The sea god wasn’t fooled and in fury struck Queen Pasiphaë heartsick, mad with love for the snowy bull from the sea, so she wept and paced and never slept or ate. She threw herself to the palace floor, thrashing about in a burning fever, tearing at her hair, until guilty King Minos again called for his trusted advisor, who set to work to end the queen’s dismay.

The next day, in a flowered meadow, among the king’s spotted cattle, under a shading oak’s spreading branches, Pasiphaë discovered the fair beast and won his ardor. The queen conceived, overcome inside the perfect wooden heifer contrived by artful Daedalus, after her passion was satisfied and turned to horror as the white bull sauntered through the oak’s shade to browse the sunlit grass.

Fearful months passed as Pasiphaë had ominous dreams and grew larger and larger, until after the normal span she birthed a healthy male child with sturdy arms and legs and chest, but whose body joined a calf’s head and sprouted hooves for hands and feet.

The half-boy was named “Minotaur,” which means “Minos’ Bull.”

The queen wailed and covered her eyes but watchful Minos demanded a stout cage to hold the hungry monster fathered by his greed and the gift of a god. Daedalus, the king’s counselor and gifted maker, quickly fashioned a prison, a torturous tangled maze with roof to block sun and moon and confound the clever captive. Sensing fate’s reward, Crete’s skillful genius then devised four wings of feathers and wax, to escape across the wide water with his one child, incautious Icarus, who tried to fly to the sun and waving naked arms fell and drowned in the sea.

The Minotaur became famished alone in his windowless house and loudly demanded food, so that his furious roar reached across the island of Crete and beyond, across the ocean to Greece where the Greeks shuddered. Every seven years the Minotaur devoured a feast of Athenians, seven fair youths and seven maidens he was fed to staunch his angry hunger.

Seven, Seven, Seven. Each set of chosen victims was forced into the awful night of howling corridors, down halls littered with discarded bones where their own would soon lie, until at last on a seventh year, among the young men and women picked for slaughter, came a hero, the King of Athens’ son, named Theseus, who had volunteered to face and try to slay the fearsome Minotaur.

Ariadne, Pasiphaë’s daughter by King Minos, was smitten by the doomed and handsome stranger, the valiant but foolhardy prince, and sought a way to save him. She wrapped a string around a boulder and gave her lover the ball of twine for his uncoiling, as he entered the maze and dared the blind confusion of the numberless passages and devious corners, tracking the echo of her half-brother’s breath and heavy tread.

Thunderous hoof-steps now trailed the intruder. Hunted stalked hunter and at a sudden turning a foul wind blew hard against the Greek’s brow.

For a bare instant’s hesitation courage faltered and he turned to run, then abruptly thought better. He leapt at the hot shadow and its fatal horns with dark plunging sharp sword, stabbing once, three times, again now and again, thrusting in passionate frenzy as if to kill the night itself, long after the creature’s rending cries and the rushing fountain ceased.

Frantic he searched and grasped again the end of Ariadne’s secret cord and fled the baffling labyrinth.

Thus Theseus emerged to fanfares and light, the deafening chorus of worshipping praise, met deathless fame and storied riches, and won in sacred marriage the prized hand of loving Ariadne.

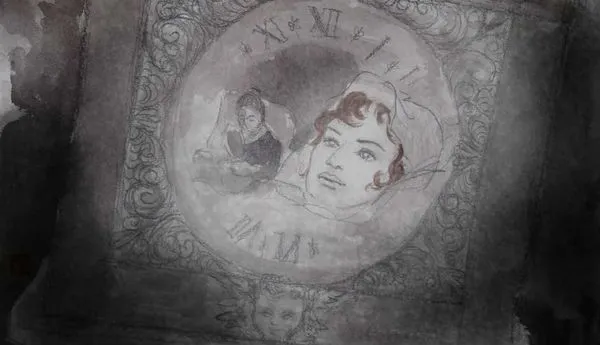

Happy years passed like warm spring, summer and autumn, until one day the good days came no more. Time itself grew frigid and unmoving and to Ariadne the world seemed tightly clutched in an everlasting winter.

She learned a painful wisdom, that man’s heady feats, like the full but fleeting moon, age and sadly wane. His satisfied heart palls and yearns, homesick for dire endeavors to fire his cooling blood, hungers for war and uncertain adventure, amorous conquest.

They forget those who gave them string.

Now Theseus wearied of his loyal, still beautiful wife. Restive he assembled crew and ship and sailed for the Island of the Amazons, to contest in gruesome combat that army of fierce women and defeat and wed their comely general and queen.

Across the mazelike ocean, Ariadne mourned love’s broken pledge, with burdened heart and downward gaze. She yearned to take the journey without return that leads deep into the Earth, all unknowing that Dionysius the Bull God harbored a stirring wish and that her fate was still unwinding.

Wild horns, crashing hooves struck and shook the Earth. The thwarted agonized deity bellowed and stormed in such tirades of wayward passion he was more frightful than the vanquished Minotaur. Then sympathetic Zeus, who once had been a white bull and fathered Minos and his brothers, keenly remembered Europa’s many charms and took thought and pity on his lust-stricken kinsman.

In kindness he changed the mortal Ariadne to a fitting partner for a god. In her honor, on Olympus at the wedding banquet, Zeus set the bridal crown of the new goddess high atop the night, amid the constellations of starry kings, intrepid hunters and bright beasts.

The proud husband trumpeted three times and dropped his heavy head from the sky’s circle of new lights. Ardently now he approached with all his long-stifled desire, then hesitated with alarm, certain his bride had moaned in terror at his wide horns and heavy brow.

All the day-birds woke, cried and took flight and all about the marriage celebration the red wine froze and broke the goblets and jars. The ground trembled and running fissures appeared that branched and spread like living veins.

Do you know what troubled the Earth?

No?

Ariadne hadn’t spoken and remained silent, a smile forming on her lips. The goddess no longer remembered Theseus or the human Ariadne and opened her arms gladly to receive her only husband. The relieved Bull God lumbered toward her once more, without noticing the cold wind starting to blow and the winter flowers suddenly blooming blood red.

Do you know what again troubled the Earth?

No?

It was a scream.

You ask whose?

Let me tell you, about three uninvited guests.

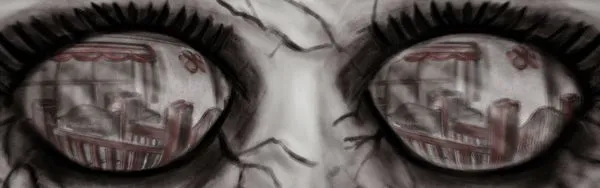

Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, couldn’t leave her starless kingdom to attend the wedding and prevent the nuptials. Although she remained in her silent chamber far beneath the gods’ holy mountain, she knew that Ariadne had been changed.

How did she know?

A chain of snakes had told her, one telling another and that one yet another, on and on, like the mothers who tell this story to their daughters. From the last snake, Persephone heard and saw what the first snake had witnessed from his rocky hole as he watched Zeus and the joyful bride and groom.

Like one snake, all the snakes reported that happily Ariadne had taken her vows, and weeping Persephone remembered the fatal day she had met her husband long ago in the upper world.

In memory again his sudden shadow fell across the far green meadow as she reached to pluck a pink spring flower, to take as a token to Demeter, her mother.

Again his cold hand had touched hers and she had screamed and screamed, making the upper Earth tremble and turn cold, until in his black armor and plumes her worried husband hurried to her door and saw the viper with ready fangs dripping venom about to pierce Persephone’s ear.

Pluto drew his knife and threw it like an arrow but the snake disappeared through a seam in the rock and the sharp blade and its hilt sealed the opening as the King of the Dead leapt forward to embrace his frightened wife.

Did the snake try to bite her?

No, he was speaking.

What did the snake say?

He asked a question.

What was the question?

Before he slipped through the cracked stone and the knife blocked the narrow door forever, the last snake’s scaly lips opened, past his white fangs his black tongue hissed his last words in the queen’s lovely ear.

What were his words?

“On the topic of men and bulls, why do daughters never listen to their mothers?”