Hand Drawn Sky

Danielle Bordelon | Miakoda Ohki

Published on 2016-05-23

She had been alive for 5692 days, 2 hours, 3 minutes, and 6 seconds.

I watched her chest rise and fall, in tune with a silent rhythm. At times, she struggled to breathe, her back arching from the effort, but she stayed in a deep sleep. The tubes protruding from her chest gave her the look of an ancient voodoo doll, pierced in vital places. Her inch-long dark blonde hair shot up from her head as if she had been electrocuted. Deep black circles ringed her eyes and dried spittle formed a halo around her mouth.

Her breathing became more and more labored as I approached. I hated the way I affected them, like I was something evil to be avoided, never embraced. Sometimes they even fought me, but I always won.

Sometimes I wanted to lose.

I was new to the job and had little of the skill of my predecessor. He had enjoyed it, had taken great pride in his work. He’d loved watching their last seconds tick by and their eyes fill with dread. He had not been one to strike quickly, preferring rather the slow decay of their body and mind. I felt, watching her, as if I had already failed him.

She opened her eyes. They were a soft shade of green.

“Who’s there?”

Her voice was soft but unafraid. I liked this one. Her eyes flicked to the spot where I stood but quickly passed over me. But then they flicked back again. My breath hitched in my throat.

“I know you’re there.” Her hand caressed the tubes protruding from her arms lightly, like a lover. “And I’m not afraid.”

Don’t speak to them, he had told me. Never speak to them. They will use their silver tongues and simpering eyes to convince you to spare them. And you cannot spare them. You cannot spare a single one.

“Well,” she demanded, sitting up with great effort and labored breath, “aren’t you going to say something?”

I opened my mouth, then shut it. Some sound must have escaped, however, because she grinned triumphantly, the smile threatening to break her too-thin face apart.

“I knew you were there,” she said, lying back among the pillows.

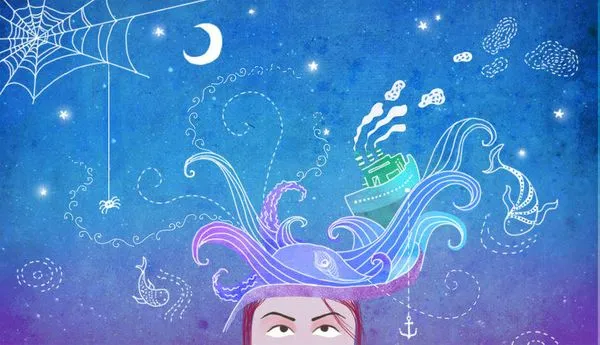

She smiled, gently this time, up at the ceiling. I followed her gaze, seeing for the first time the mural of the night sky painted clumsily over her bed.

“They didn’t even get the constellations right. I just want to take a sharpie and fix them. I don’t think I can stand anymore, though. Especially not on this rickety bed. You see that?”

She looked at me, pointing at a constellation on the ceiling. Despite my training, I nodded.

“They mixed up Canis Major and Canis Minor, see? Rookie mistake.”

She was quiet for a long time, staring up at the ceiling. I could only watch her. I had visited millions of people in the last 349 years. After the first 100, they’d all started to blur together. But I’d taken particular time with her case, hoping without hope that perhaps my orders would be different this time.

“I’m Annabel, by the way.”

I know, I wanted to say. Annabel Marie Edwards, youngest of three sisters and the most ferocious fighter. You’ve been battling the cancer for exactly 605 days, 23 hours, 46 minutes, and 1 second. Your parents and sisters have watched as it slowly ate away at your body. I’ve been here, I wanted to say. Watching, waiting. I’ve seen everything.

I’ve seen your mother smile and tell you everything’s going to be all right. I’ve seen her sob in the solitude of the bathroom until her chest hurts and her tear ducts dry up. I’ve seen your father stare at your picture for hours in his office, mouthing ‘why’ and wishing he could run from the pain. I’ve watched your sisters shoulder the burden at school, dodging unwelcome questions and curious glances, guiltily thanking God for their good health. And most of all, I’ve seen you. Laughing, smiling, babbling, wondering, living. I’ve seen your darkest days of doubt and anger. I’ve watched you fight through them all. I know you, Annabel, I wanted to say.

But I didn’t.

Instead I walked to her bedside, watching her eyes follow me in the dark.

“Will it hurt?” she whispered. She suddenly looked like the fifteen-year-old child she was.

I shook my head. Gently, I took her in my embrace, letting her vibrant soul ease out of her body. He would have disapproved. He had liked to watch them fight for their last moments, although their fight would be in vain. When she was gone, I shut her empty eyes.

An idea blooming within me, I rummaged in one of the hospital drawers, frantically searching. I had to be gone before they came back. They would not be able to see me, of course, but I disliked witnessing the tears.

I held up a black sharpie in triumph and crossed over to the bed, perching precariously on it; I began to write on the ceiling.

Minutes later, I surveyed my work. Canis Major and Minor were fixed, in their appropriate positions in the sky once more. Annabel would be pleased.

I shook my head at the thought.

“Rookie mistake.”