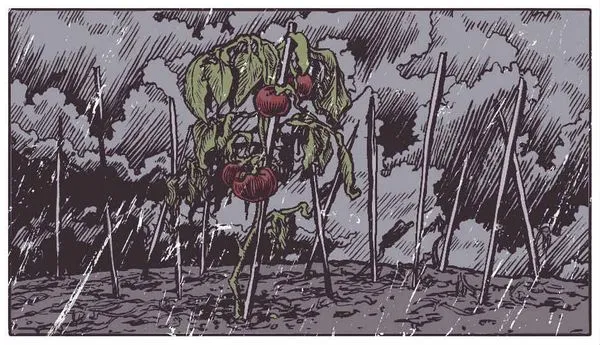

The Valley of Doom

Stephen V. Ramey | Sue Pownall

Published on 2013-04-20

The light was failing as we started down Route 424 into the Valley of Doom. That wasn’t its map name, but Bruce and I had called it that on our annual excursion over the mountains to Grandmother’s house. Now it was my fiancé in the car with me, drowsing against the passenger window.

“Sasha,” I said, “we’re about to enter the valley. You might want to wake yourself up a bit so as to appreciate the splendor of our descent.”

She yawned and sat up straight. “It’s quite… haunting,” she said in that noncommittal tone of hers. I couldn’t tell if she was serious.

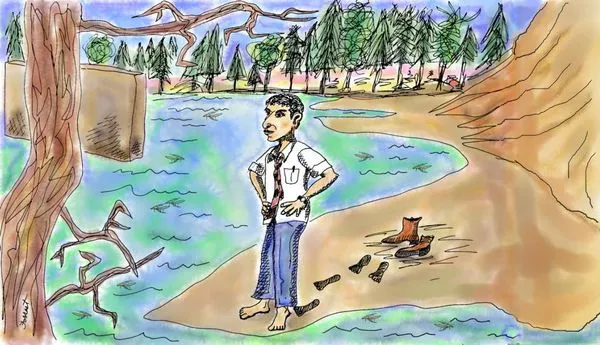

“It’s actually called Copper Wash Canyon,” I said. “There’s a river at the bottom, more like a creek, actually. I guess they had a copper mine down there at one time.”

“The road winds down into the canyon like a ribbon turned back upon itself,” Sasha said.

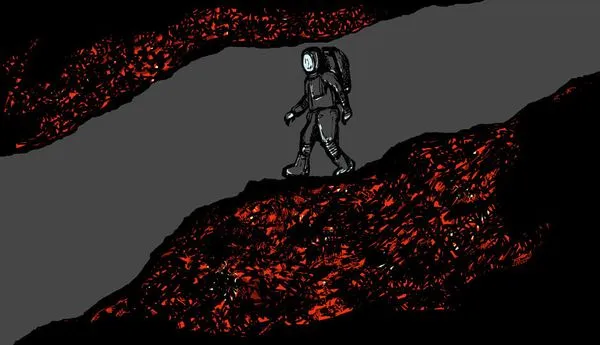

I gazed through the windshield. Sasha was right about the road, but she was also wrong. It did superficially resemble a ribbon, but it looked more like a stream of molten slag to me, white-hot liquid clotted with shadow, coiling down into darkness. I imagined a waterfall of sparks at its terminus, twisted men with goat horns pounding anvils, turning that light into the darker foundation of our world.

A sunset trick. The pavement would be gray, not white, and it could hardly flow. That was a river’s business, not a road’s, though I did recall reading that glass flows. Very slowly, the silicon pane distorts downward as its molecular structure gives in to gravity.

“How much farther?” Sasha said. Another yawn. A blink of those pretty eyes.

“From the valley opening it’s maybe fifty miles through farmland,” I said. As the corncob flies, my dad used to say. He’d not been a fan of moving back to be with Mom’s mom in her final years, but he had done it. That was the way a relationship should work, I supposed, but I always wondered. I hadn’t been happy to leave middle school friends behind and take up high school on foreign terrain. Farm boys and apple pie girls, 4H and county fairs. The experience had marked me for sure.

“Do you think we could stop at a gas station?” Sasha said. “I need to pee.”

“Sure, if we find one. It gets pretty desolate out here.”

We drove through shadow, and emerged to a new reality. The slope steepened. The road seemed to narrow. There was barely a berm now, just a metal guardrail like some lonely sentinel at the edge of oblivion. I clutched the steering wheel.

“Don’t you think you should slow down?” Sasha said. She leaned away from the window. A hundred yards below, the road continued its molten descent.

We’re part of the flow. It was a startling realization. The valley had us. The Valley of Doom.

I tapped the brake. The car slowed, but also pulled toward the guard rail.

Sasha smiled nervously. Her teeth were very white. “Do you think she’ll like me?”

“Who, Mom?”

“Yes.”

“Of course she’ll like you. You’re going to be her daughter.” A tire hit something. The steering wheel twisted against my grip. Only momentarily, but it sent my heart pounding.

“I hope she likes me,” Sasha said. “I’m sorry about your dad.”

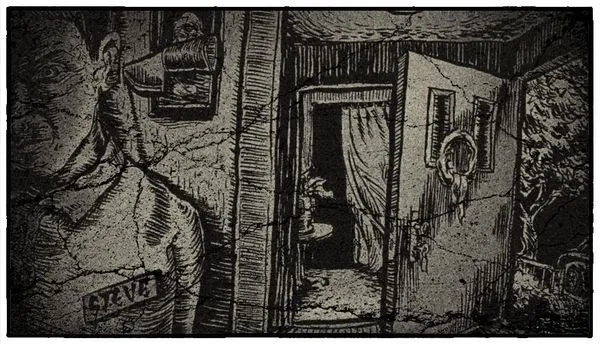

My inner child cringed. I thought of Dad lying in blood, the shotgun angling from his corpse like an unwilling accomplice. I’d only seen the one picture. They wanted me to understand Mom’s mental state. They wanted to change my condemnation into comfort. And I had tried, I’d tried to put myself into her place and feel the agony (guilt?) that drove her into solitude. Mostly I pretended. Some emotions are impossible to steer.

It had been Sasha who insisted we visit before the wedding, Sasha who pushed me to re-approach my roots. And now, here we were, halfway down the valley, half-swallowed, half-lost. We were slag in the downhill flow.

How long before Sasha asked me to alter my dreams? How long until I gave up like Father? I wanted to design games. I wanted to write new worlds, create new paths for people to escape their mundane. I wanted—

Sasha placed her hand on my thigh. “Can we visit the cemetery?”

A shudder ran through me. “She had him… he was cremated.”

“Did she keep the ashes?”

“I don’t know.”

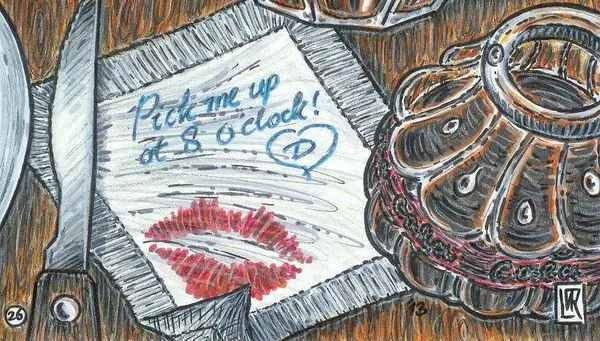

“How could you…?” Her hand returned to her lap. “Should I call her Marion? Mrs. Stekolfsky? What do you think she’ll want?”

“Marion, I think.”

“Okay.” Sasha peered through the side window. An eighteen-wheeler whooshed past. The car buffeted. I tapped the brake. The car pulled. I released. Our headlights illuminated only a few yards of the road ahead.

“I’ve been thinking,” Sasha said. “What would you think about moving out here?”

“Here?”

“The job market is bad in the city,” Sasha said. “It’s not like either of us has great prospects.”

“You’d rather farm?”

“No. Think of the cost of living, though. We could live on almost nothing. Maybe your Mom would take us in. I mean we could pay rent, but…”

“You don’t even know if you’ll like her,” I said.

Sasha laughed lightly. “We can always leave. The road runs both ways.”

Does it? I pressed the brake pedal. The car pulled toward the guardrail. I turned through the final curve into shadow.