The Convalescent

Published on 2013-05-07

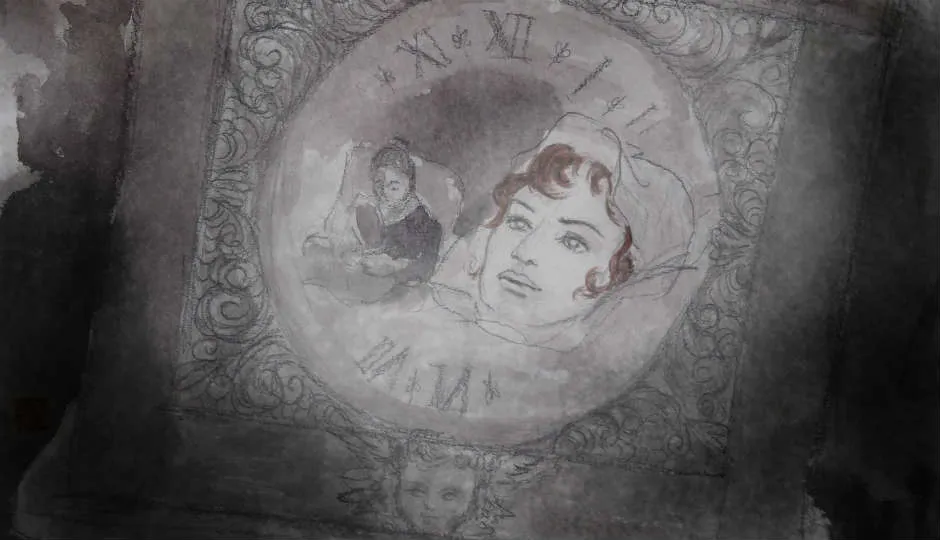

Hendrika Boer sits up feverishly in bed; aware of soft blue light filling the small fisherman’s cottage. Auburn hair pokes out beneath her white cotton convalescing cap. At first it looked as if it was some unearthly light emanating from the nearby old gilded clock. A family heirloom dating from the eighteenth century; it was given to husband Willem’s potato farming grandparents by local landowners, the noble de Groots.

“Quickly, Elizabet. Please stop your knitting and just look at the clock face, has it become blurred once more? I swear that smiling cherubim grins when my back is turned. What do you see?” Hendrika whispers, careful not to wake her sleeping son.

“Why there is nothing at all. Just a normal clock face showing me the time as I would expect. You are still a bit delusional I’m afraid. You simply must stop these superstitious notions you have about that clock. Now lie back down and rest.”

Elizabet pulls the cream and brick wool blanket around her.

In the past few weeks spring has arrived but it has been a long dark haul. A difficult birth and a weakened immune system in a harsh winter meant sister Elizabet travelling regularly from Haarlem to nurse both her and Jakob. Elizabet had stayed over, sleeping on the rough flagstone floor when mother and child were struggling through Christmas. Willem doesn’t like it, but then he always felt uncomfortable accepting charity. Elizabet dispensed figs and kindness knowing that Reverend husband Franz completely approved; seeing the frequent coach journeys to and from Zandvoort as one of the necessary sacrificial crosses we all must bear. Yet herring still had to be caught and livelihoods earned. Little Jakob stirs slightly in his Moses basket.

Windmills near open dune fields seem more prominent in bright July sunlight. Fish wives dressed in stripy cotton laugh and talk amongst themselves, balancing baskets of fish on their heads. On daily journeys back from market along the Visserspad they spend money at the Stinking Pail Inn, drinking and complaining about men and the price of fish. Drinking is an indulgence that Fredrick Stoffels won’t allow; in his weekly questioning of wife and daughters in Haarlem Lutherse Kerk clergy man’s cottage; he reminds them of the importance of scriptures and of the interpretation of those holy words in to daily conduct.

“Come, Hendrika. And you too Elizabet. The picnic baskets are not so heavy as the baskets those poor fishwives carry. So stop complaining and be grateful. Now we have this good opportunity to enjoy a summer’s day out and I’m determined that it will be an enjoyable time for all. It will give your poor mother a rest too, recovering as she is.”

At the mention of long suffering mother back at the cottage, both daughters fall in to shameful silence. Would father ever understand what it is to yearn for love? Hendrika mutters quietly; her nineteen year old mind excited at the thought of meeting some as yet unknown man. It is alright for Elizabet, her older sister — she is so solemn. She watches her father and sister walk on ahead, both of them dark haired and fearful of God.

Two horses labour hard, pulling the flat bottomed boat out on to the beach. Men shout encouragement at them, their fisherman boots glistening in the sun. Hendrika watches, fascinated. What a life of freedom out on the rolling seas. They’d eaten the simple lunch with cheese and hams, now Fredrick is dozing and Elizabet earnestly reads. On the pretext of wanting to walk along Boulevard Barnaart for sugared candies; Hendrika singles out the small café-bar where she sees the fishermen go. She’s never been in a smoky working man’s café before and nervously sits alone at a table, waiting to be served. Glancing towards the door, she catches the bright blue eyes of a young man who then cautiously asks her if she’s a local girl. Willem Boer says he lives with his elderly mother on the town’s outskirts. He isn’t impressed by her telling him about casting lunch time bread rolls upon sea waters.

“I don’t care whether it’s in the bible or not. You are lucky to afford to throw bread away like that. It seems to me that people only have the beliefs that they can afford to have in life. I’m just a fisherman. I like the flat lands of our country and seeing where I’m going with uninterrupted views.”

Later, in his letter, he said his mother would like to meet her, that it must be hard being a clergyman’s daughter and that he hoped the railway would never come to Zandvoort because it could mean the death of the fishing industry. Hendrika wrote back describing how her own mother had died and how poor constitutions seemed to run in the female side of her family. Call it God’s will. My father says it’s not to be questioned, she wrote. No such thing, Willem replied, in forthright country manner. It is just your own will power or lack of it. He exhorted her to get more fresh air, saying that he’d visit the church if her father could stand a visit from a humble Dutchman.

Hendrika yawns herself awake to sounds of her sister’s clicking knitting needles. Jakob looks as serene as the golden cherub above the family heirloom clock; the clock that mysteriously seemed to mist over. Once, after she and Willem had a terrible argument; she’d looked in to the clock’s face only to see a mirror and her own face reflected back. It always happened after some emotional upheaval; but both reasoning husband and religious sister dismissed notions of anything unnatural. It made Hendrika appreciate her elderly mother in law more — and it was Grandma Boer who spun the rich purple cloth which lines Jakob’s Moses basket. It is the basket Willem had as a baby and don’t you heed his grumblings. You trust your own mind; she’d said. Grandma Boer said the de Groots family had second sight and soon Hendrika will visit the old lady again. I will listen to my self, she silently vows as Willem’s heavy boots thud on the doorstep.