The Call Was for a Foot

Published on 2014-05-14

Goosedown flakes fell clear and defined against the backdrop of the dark evergreens across the valley, and Clad stood leaning forward, his forearms atop the deck’s rail, the flask dangling from a hand. The call was for a foot, ending sometime after midnight: Santa was going to have a rough go of it. He tipped the flask to his mouth, took the burn, and sensed this might be one of those nights when his thoughts would fasten on her, and, of course, her departure.

He’d lost her to a clown. She said the proper term was rodeo protection athlete, but Clad figured if you wore makeup and ran around with a dozen bandanas tied to baggy overalls, you were a clown, even if you had to dodge a bull or two. Clad enjoyed seeing her flustered by his misnaming of her new man, but now that their divorce brawl had started in earnest, each spoke through their lawyers, and the minor satisfaction of watching her face redden had come to an end.

But the battle for the cabin had begun. The cabin was their retreat, and looking back, Clad realized its therapeutic value was one of the few things on which they could completely agree, a balm for a marriage that had begun to fester years ago. One thing was certain, both of them wanted it, and all the lawyerly phone calls and meanderings of jurisprudence would not persuade either side to start house shopping.

Like any other place, it wasn’t perfect. When night fell, the woods became as black as a mine shaft, swelling imaginations beyond the normal bounds of logic. Grizzly bears roamed the slopes, mountain lions prowled the ledges, and wolves packed along the river, growls and screams and howls ripping the night from time to time. However, in their eleven years there, they’d heard roars boom through the valley on three separate occasions, sounds they couldn’t assign to any known animal, roars powerful enough to vibrate their clothes, chilling enough to prickle their scalps. During these times they’d mention the relief of being each other’s company, thankful they didn’t have to be alone; something he couldn’t say tonight.

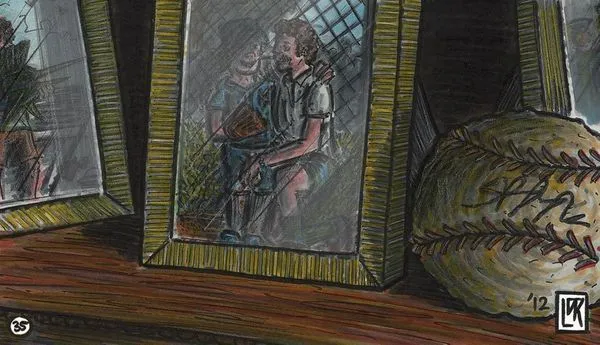

Evening began dimming the valley and he walked into the warm house, locking the double doors behind him. Flames from the fireplace made the varnished wooden beams and floor boards appear shiny and wet, and Clad recalled a wreath over the mantle and a tree from the valley in the corner, but not this year. A ball-less, two-foot tall artificial—the tree he used in his office—sat on an end table; non-blinking reds, blues, greens, and oranges staring back at him. The next several hours would see dinner from the microwave, bills at the living room table, computer solitaire, more flask, and an early bed. Pulling a poker from the iron stand, he jabbed at the logs, collapsing them onto the orange embers in small puffs of sparks. Best to take that fire down now, he thought, and start the night.

Morning brought blue skies and a brilliant sun. He shielded his eyes against the bright snowscape beyond his window, wondering if the snow blower in the shed would start, or if the gasoline in it was still good. Either way, by muscle or machine, he understood hard work was a reliable treatment for excessive thinking.

After some thick-slab bacon and grits, he layered up and opened the side door. A swirl of powdery snow rushed in from around the frame and he pulled the parka zipper to his chin. He shut the door behind him, and stopped.

A confused moment passed before he considered the size, then the shape, of the footprints. The prints—not from shoes—revealed a line of barefoot impressions, individual toes and rounded heels obvious, leading down the driveway toward the main road. Drawing in a deep icy breath, he placed his boot beside one of the prints. Clad judged the track to be no less than eighteen inches long, perhaps seven inches wide.

He squatted dizzily, pulled off one of his gloves with his teeth, and touched the impression with his bare fingers, examining its edges and depth.

There was no contour to the sole, either in ball or heel, just flatness. The toes were too distinct, too perfectly splayed. He stood and walked along the tracks. Nope, he thought, too close together, something with feet this big would have a much longer stride. Faint tire marks were visible leading away on the main road. Clad threw back his head and laughed. It all looked like something manufactured from a set of poorly jig-sawed plywood feet, and as he plodded toward the shed he realized she had given a pretty good gift this year.

[joezabel]