The Navigator

Published on 2015-07-16

The Utah sun had already set before my father remembered the chairs. Other family members were coming by for the barbecue, and there wouldn’t be enough seating without some folding chairs from the church. I stepped up into his Lincoln Navigator to help out.

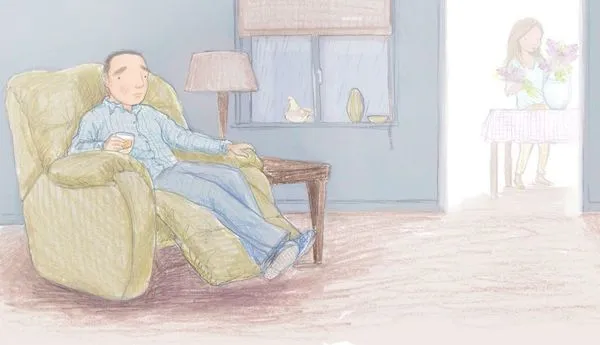

“Three hundred horsepower,” said Dad, “five-point-four liter engine. Climate control. Hear that sound system? Seven speakers that don’t buzz or rattle.”

It was a big ride. My leather seat must have been over four feet from the ground, and I could look right down into other people’s cars—sedans and station wagons like I’d grown up in, driven to church every Sunday in rain, heat and sweaty discomfort. My six siblings and I had battled over seats, with the losers in middle seats away from windows in the back. The best seat was by the window behind Mom, because Dad’s swinging fist couldn’t reach you there.

Now I was in the front passenger position in a luxury vehicle that glided over the road like it was a bed of marshmallows. There was plenty of room in the back for piling up some folded chairs. We could have stuffed any number of kids back there. Dad whistled as we floated along on the crosstown street. A Honda Civic swerved to get out of our way.

I used to hate going to church. The whole family would be crammed into the station wagon, and all of us dressed up in scratchy church clothes. There was no air conditioning and, if you weren’t next to a window, no fresh air. I remember my gorge rising as I sat with my two brothers in the back seat facing rearward. I was dizzy and near vomiting all the way to the chapel. Church meetings were long and boring with a series of local men giving long-winded speeches and babies crying in the pews. It was all done under duress, with Dad’s powerful backhand for an enforcer.

He’d purchased the Navigator a few months earlier, just after the real estate project had collapsed. He’d taken sixty thousand dollars from the contracting funds he said he was owed. My sister and her husband objected, as they were partners in the business and suddenly left with nothing when it dissolved. Dad was owed everything left. When they tried to withhold some of it, he threatened to sue them. So they weren’t going to be there for the barbecue. But I had plenty of other siblings to fill out the chairs. We still needed a stack.

At least we aren’t coming here for services, I thought, as we pulled into the unlit church parking lot. Dad parked the Navigator by a small cinder block out building behind the chapel. A mini van pulled in, its headlights sweeping over the dash as it turned to park next to us. “That’ll be Brother Biggs with the storage key,” said Dad, cracking his door. We stepped out and met the man in the dark. I watched him open the shed door with difficulty, as he had to work by feel.

“You could have called me while it was light out,” he said to Dad.

“I, I tried to,” said my father. He didn’t sound like he believed himself, which was uncharacteristic. Was I hearing the same voice that sent me cowering into the sick-inducing backward seat? This was a man who drove off his own daughter with lawyers. Who the hell did this Brother Biggs think he was, pushing my Dad around? I would have said something, had I not been muted with nerves. I remembered thirty years earlier when my father had seen a brown bear in our campsite at night. He’d screamed like a terrorized woman in a horror movie, triggering my lifelong fear of bears. Now I stood in a darkened parking lot in a darkened state, a forty-year-old kid with no defenses.

We loaded the chairs blindly, working by feel.