Love and Anger at 80, According to Elmer

Published on 2014-04-04

When ancient Elmer was young and dashing and on the prowl, he would wait for a phone call about love or anger from someone important to him at the time. Over the years more than a few women had reason to call. Some were happy with Elmer and some were not.

According to Elmer, more than a few of those women today, five or six decades later, take advantage of the new technology and Google his name in an effort to find him. Many want to confront him for past promises not kept. Some want to see him again if he’s single, widowed or divorced. Others just want to see him again, whatever his marital status.

The vote on him, Elmer says, is split down the middle. He fooled some of the women some of the time but the others never forgot. At age 80 he wishes most of them—but not all of them—would.

“What can I tell you,” Elmer says. “Besides drinking, the only thing I was good at in life was talking to women until they caught on. I may be old but I can still talk nice to a lady. I specialize in buncombe and balderdash. But I can’t run any more from the angry ones. The legs are gone.

“And that damn Google can be a real problem. I guess my address and phone number got on the Internet somehow and some ladies who are still able to get around have come looking for me. It’s happened more than once. I wouldn’t be surprised to answer the door some day and find one of them in an electric wheel chair. But all of them, good and not so good, had energy and spunk.”

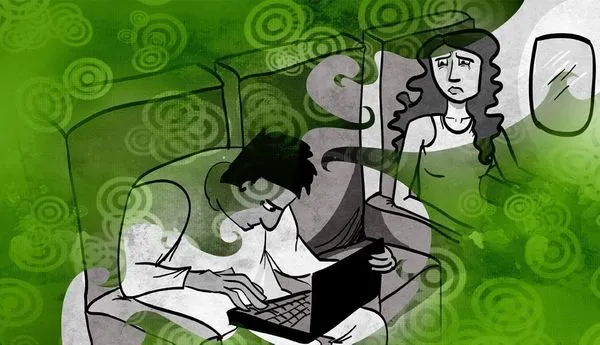

His many children are now adults, he says, but they wasted his money in college. Instead of applying themselves to their studies, they would wait for an email about love or anger from someone important to them for that semester. The following semester, he says, they would wait for an email from a new love interest. This would go on every semester until they flunked out or managed to graduate. Email in the lives of his children was not a positive thing when they were in college.

“I have 12 kids,” Elmer says. “Six have degrees and six flunked out. More of the flunkers have jobs than the graduates. What does that tell you about this economy? And what does that tell you about my kids? The apples, I guess, fell close to the tree.”

Elmer also has quite a few grandchildren, most of them adolescents. They waste time in school, he says, waiting for a text message about love or anger from someone important to them for a day or a week or over spring break. Texting is not a good thing, Elmer says, in the lives of his grandchildren. And it won’t be a good thing for any of them able to get into college.

“Kids today,” he says, “are on a carousel, especially the girls because they trust boys and most teen-age boys are louts. I can tell you that from personal experience because I was a teen-age lout for several wonderful years,” Elmer says.

“As a teen-ager, if I ever told a girl the truth I must have been drinking beer in back of the Masonic Lodge earlier that night. We had no dope back in those days. Never even saw the stuff. Wouldn’t touch it if I did. But we drank a lot of beer on the weekends and maybe a little vodka and Squirt on Sundays. After church, of course. Times were different back then. You could meet a lot of nice girls at church.”

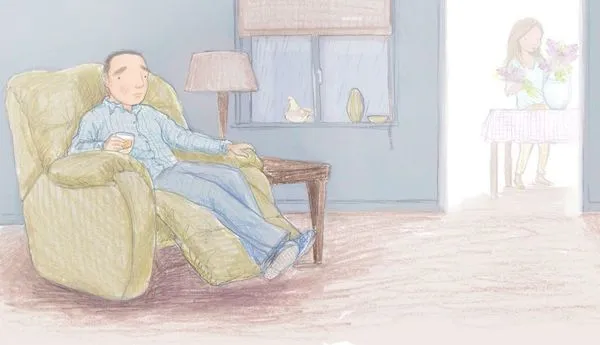

Now in his dotage, and feeling the effects in his joints and muscles, Elmer still maintains that love or anger shouldn’t arrive by phone, text message or email. It should arrive in person, smiling or spitting with rage. He’s had it happen both ways. And he’s ready for more if time permits.

Elmer doesn’t have a computer or cell phone so emails and text messages never ruin his day. He has a land-line phone to make outgoing calls but he adjusted it so he cannot hear the ring of incoming calls. He did that two months ago after Bertha, a woman he took to her prom more than 60 years ago, found his phone number on the Internet. She called twice a day for a week until Elmer turned off the ringer, as he calls it. He never turned it back on. Now he calls out once a week for a large meat-lover’s pizza and two quarts of beer. He’d make the same order more often, he says, but he has to watch his cholesterol.

Elmer, however, would not be disturbed if Bertha—or any other woman from his youth—came knocking on his door. He has always believed that love or anger should pound on the door with great emphasis—like the baton of a policeman at midnight yelling the music’s too loud, stop the party or everyone’s going to jail.

The pounding would have to be loud enough, Elmer says, for him to hear it—and even louder at night to roust him from his bed in his nightshirt to search for his teeth and toupee before he answered the door. He wouldn’t care who’s pounding as long as it was love or anger and not some guy in a ball cap selling aluminum siding.

“Every man, no matter how old, deep in his heart wants to hear one more coo or even a gripe from a woman,” Elmer says. “In fact I’d like to hear both before I go—and I won’t go quietly—into what Dylan Thomas called that good night. Did you ever read his poems? I did and I thought if I’d had a brother, it should have been Dylan Thomas. Or Salvador Dali. Did you ever see his paintings? I see life the way he painted it.”