A Disgusting Thing

Donal Mahoney | Kristy Lankford

Published on 2014-06-18

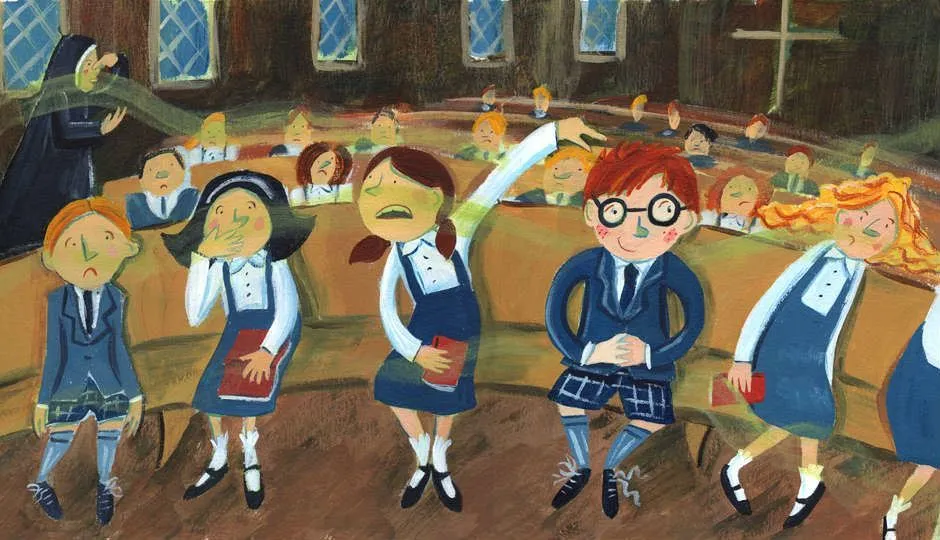

It’s a disgusting thing but Paddy Gilhooley, who knew better as a child, had begun farting in church very early in life. He started in grammar school, many decades ago, long before the nuns selected him in fourth grade to be an altar boy to serve Mass.

The Mass was then said in Latin with the altar boys’ responses also said in Latin. The nuns picked Paddy because he was tall and was able to memorize things rapidly. By training him in fourth grade, the nuns believed Paddy would be able to serve Mass for the next four years till he graduated from grammar school.

Paddy was less than thrilled to be singled out for this honor. He had nothing against God or the Mass but he knew that fourth-grade altar boys were always assigned to serve the Mass at 6:30 a.m., way too early in the day for Paddy.

Being selected to be an altar boy, however, helped Paddy’s grades even if more than once the nuns had to summon his father to the school about some aspect of his behavior that did not live up to the code at St. Nicholas of Tolentine School.

St. Nick’s was a fine school whose mission was to educate the children of immigrants whose fathers had jobs good enough to buy small bungalows in the neighborhood known as Chicago Lawn. This was back in the 1940s when food was cheap, houses were cheap and salaries were commensurately low.

Most of the immigrants were from European countries—Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Italy and Ireland. Parents were interested in their children getting an education good enough for them to pass the entrance exam at one of the parochial high schools in Chicago. These high schools were renowned for offering college preparatory curricula. Tuition was around $250 a year. That was a big sum in those days but Paddy Gilhooley’s father, an electrician, and a non-drinking Irishman, had already saved the $1,000 required for Paddy’s four years of high school. Now Mr. Gilhooley was saving to send Paddy to college.

Paddy’s father wanted the best for his son. Once he had enough money put aside for Paddy’s college education, he planned to save more money to put him through law school. Mr. Gilhooley didn’t emigrate from Ireland to have his son work with his hands. No sir, his son would go to law school and work with his mind. That much was settled.

Paddy, however, was a bit of a scamp when no one was looking. He discovered early on, for example, that one way to square the score with the nuns who required good behavior at all times was to fart in church, preferably in serial fashion, one missile after another, silent but, as his classmates aways said, deadly.

He started doing this in first grade when he had to sit with his classmates in one of the first three rows in church. These were the pews reserved for the first-graders at the Children’s Mass. Right behind the first graders were three rows of second graders. And behind them, three rows of third graders—and so on. The procession continued, three rows at a time, all the way back to the eighth graders who occupied their own three rows in the rear.

The eighth graders were monitored carefully by the nuns. One false move and any miscreant child would be led by the ear out into the foyer of the church, where he—and it was always a boy—was dealt with summarily by the principal, usually the toughest nun in the convent at the time and always an immigrant from Ireland. In fact, the whole convent consisted of 16 nuns imported from Ireland to deal with these children of immigrants who were not, by any means, a refined group. Quite the contrary.

Paddy realized the nuns were only doing their job—trying to maintain order in God’s House. But he enjoyed getting involved in devilment and looked forward to being in eighth grade when he’d be able to sit in the rear of the church where the nuns kept a close eye on boys like Paddy, most of them feisty to a fault, ready to do anything at times to create a little commotion.

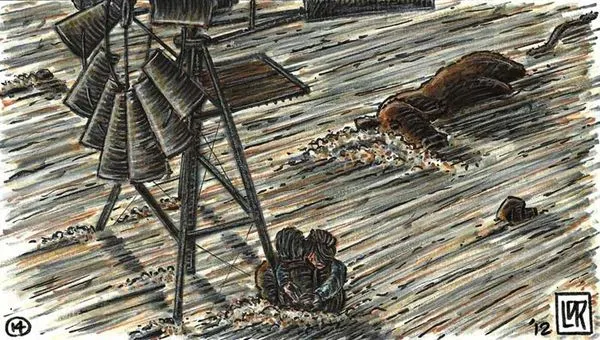

In first grade Wally learned early on that farting in church was especially troublesome to his classmates, especially the girls who seldom if ever misbehaved. It took awhile for the nuns to identify which child was stinking up the first three pews at the Children’s Mass. But when several little girls sitting behind Paddy began pointing at him, the jig, so to speak, was up. Sister Mary Lorraine led Paddy down the aisle by the ear and placed him in the custody of the principal, Sister Marie Patrick, a stout bullet of a woman who did not suffer misbehavior happily.

“Why did you do that, Paddy, at Mass, especially? Surely, you must know better. Your parents will not be happy when I tell them.”

Paddy, though only seven years old, had learned to keep a straight face and deny anything he was accused of. But it didn’t help that despite great efforts by his mother, there was no way to comb his hair since it featured seven cowlicks—the barber had counted them for his curious mother. She had tried gobs of the most popular hair tonic of the day, Wildroot Creme Oil, but the cowlicks always popped up, often in the middle of Mass and just about the time Paddy would let the first of several farts fly.

“Sister, I didn’t do nothin’ at all,” Paddy finally said. “I think it must have been Stanley. He eats Polish sausage and sauerkraut. Ask him.”

But Sister Marie Patrick knew better so she led Paddy into the little office in the back of the church until Mass was over. Then she waited by the doorway to see Paddy’s parents after Mass so she could discuss the problem with them. She really didn’t know what to say to them but she figured it out by the time Mass was over.

Upon hearing of the charge against Paddy, Mr. Gilhooley, in his best suit and tie, was outraged. How could anyone, especially a nun from Ireland, say a thing like that about Paddy, who was going to law school in a few years.

Paddy himself, standing off to the side and watching the proceedings, enjoyed everything immensely but kept a stoic face. Even at this age, with his spectacles always slightly askew, he looked a little like a very young James Joyce or maybe George Bernard Shaw.

He never smiled or laughed when he was in the vicinity of people of authority, especially his father or the nuns. His mother had seen him smile several times and had told his father that Paddy was not as serious a child as his father thought a lawyer-to-be should be.

Finally, however, Sr. Marie Patrick, after mentioning to Mr. Gilhooley that she was from the same county in Ireland that he was, convinced him that indeed Paddy had been stinking up the front of the church during Mass.

“Where did he learn such behavior,” Sister asked Mr. Gilhooley, who said he had no idea and looked at Mrs. Gilhooley, who knew full well that young Paddy had grown up in a home where his father not only farted with bravado but also used to sing, after each fart, an old ditty that was famous in the neighborhood:

“Beans, beans, the musical fruit. The more you eat, the more you toot.”

Mr. Gilhooley was especially apt to fart and sing on Saturday afternoons while listening to the radio as Notre Dame stomped on some lesser foe in a football game. The more points Notre Dame would score, the more Mr. Gihooley would fart and sing.

And when Paddy’s mother would complain that her husband was setting a bad example for Paddy, Mr. Gilhooley would explain once again how many farting matches he had won as a young man in Ireland. As the story would have it, Mr. Gilhooley would show up at the pub for the matches held late on a Saturday night. His presence was frowned upon because he didn’t drink anything stronger than ginger ale.

Finally, Mr. Gilhooley decided to agree with Sr. Marie Patrick that young Paddy was guilty of what might not be a mortal sin but certainly qualified as a venial sin at the very least. He was also afraid his wife, an innocent woman if ever there was one, might pipe up and say Paddy had learned to fart from his father while they listened to Notre Dame games on the big console radio in the living room.

“Sister, I tell you this,” Mr. Gihooley said. “If Paddy ever farts in church again, you smack him with that ruler of yours right across his keister and don’t stop till the little bugger starts crying. Then you call me about it and when he gets home, I’ll wallop him again. You and I will put a stop to this once and for all. Paddy is going to be a lawyer and no Irish lawyer farts in church.”

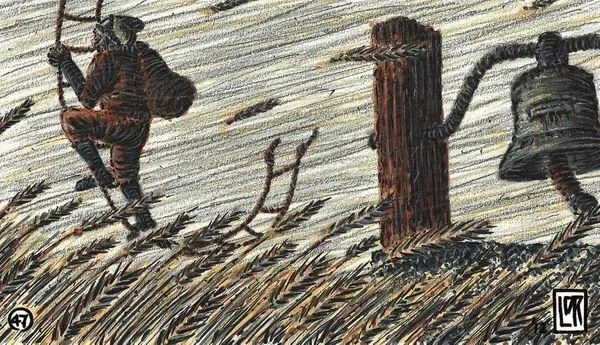

Sr. Marie Patrick appeared mollified and released Paddy to his parents. His father led him out of the church by the ear for the long walk home. Paddy knew what he was in for once they got there. His father would take him to the attic door and open it and show him the big black belt that hung drooping from a hook. Mr. Gilhooley had even spliced the end of the belt so it would look like a serpent’s tongue.

Whenever Paddy acted up around the house, Mr. Gilhooley would take the belt off the hook, wrap it around his fist and smack the tongue of the belt against his palm while telling Paddy if he ever did it again–whatever it was the boy had done on that occasion–the belt would be applied to his keister till he couldn’t sit for a month. Paddy would immediately show sheer terror and say that he would never do whatever it was again.

Year later, Paddy, now a retired attorney, could laugh about all this as he told the story to his grandchildren. It was especially funny to Paddy because his father never hit him with the belt even though Sr. Marie Patrick had called his father several times to report that Paddy had continued to fart, albeit in the classroom and not in church.

Notre Dame in those years won several national football championships. As a result, Mr. Gilhooley continued to fart proudly and sing his heart out on many Saturday afternoons in autumn.

In eighth grade, Paddy was allowed to join in the farting himself but he would never join in the singing. His mother would never have allowed it. The poor woman couldn’t tell one fart from another so she knew nothing about Paddy’s participation at that level. But she always told neighbors that when you compared Paddy and his father, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.