Misfit

Aarushi Gupta | Alankrita Amaya

Published on 2015-10-22

Heat wave in Delhi was unbearable.

Correction, heat wave in any part of the world was unbearable. The persistent, sultry gusts of wind and dust would hit one’s face like inspiration hits a struggling writer — out of the blue, when you’re least expecting it and yet impatiently, desperately awaiting its arrival.

It’s only when the storm has passed you realise that all this time, you’ve been holding your breath.

it’s only then you realise how much your lungs lust for a taste of air.

You’ve been on a journey, to God knows where and have unknowingly found your way back.

Sunita shook her head violently, trying to get the dust and twigs out of her hair, her twin pigtails swinging freely, and landing on her back with a heavy thud. Her red backpack, too big for her tiny frame to carry, almost touched the ground, sagging with the weight of unread textbooks, solitary lunches and crumpled up notes she had written to her friends, telling them how much she loved them, which never reached their destination.

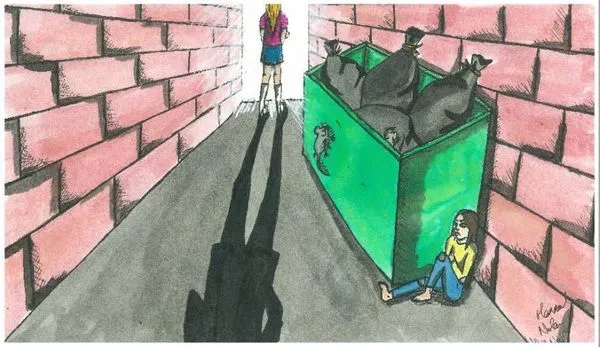

“Friends,” she scoffed, as she made her way through a sea of sheep on two legs, who carried briefcases in their hands, a sense of urgency in their minds and fear in their hearts. The definition of friends put her off more than any amount of homework could. A friend, she mused, was someone you knew. Someone on two legs. Someone you could see, with your naked eyes. Someone who others could see. No one in school, or in the neighbourhood, or in her family had ever seen Sunita walk down the street with someone on two legs, or on 4 legs, for that matter.

Sunita was a loner, not a lone wolf.

She was a misfit, not a black sheep. Being a black sheep entailed you were at least a sheep.

If the world was a jigsaw puzzle of planet Earth, Sunita was a small rock straight from a planet no one had heard of. The planet was unheard of, hence it didn’t exist. Henceforth, it wasn’t real. Which implied that Sunit wasn’t real. And what isn’t real, is worth no one’s time.

Sunita wasn’t worth anyone’s time.

Except perhaps a book’s.

She made her way through the busy streets of chandni chowk, her senses assaulted by the smell of sizzling kebabs, freshly made dough slapped onto a hot tawa, spiral jalebis dancing in hot oil, the allure of crumbled up, half-standing historical structures and havelis, the air around them laden with secrets of a life that flourished and perished, and now merely co-existed.

She stopped in front of an abandoned, half broken structure with a tilting sign. In big, bold letters, it said Chandraban library, open Monday-Friday, 12-5pm. She pushed open the heavy doors of the library and made her way in, tiptoeing so as not to disturb the thousands of others present in the space.

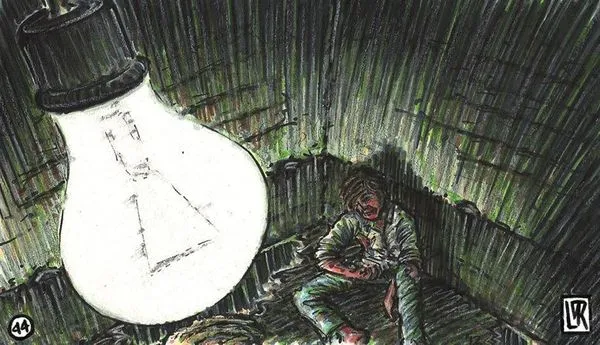

It was past 5pm, and Sunita was sure that by then, all the books were fast asleep.

She quietly made her way to the secluded bookshelf, which was painted a hazy red, the kind of hazy red the sun left behind when it disappeared behind the clouds.

Sunita pressed her watch with all her might, and a few seconds later, she was greeted by Mickey Mouse’s neo-glowing, smiling face. Using it as her flashlight, she found a section on the bookshelf where her friends were fast asleep.

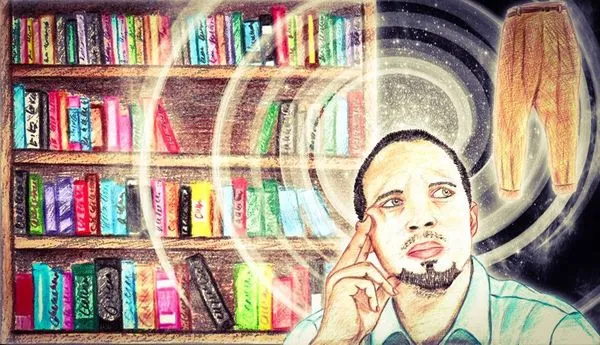

Friends who no one saw walking with her down the street, because they didn’t walk beside her, they walked with her in her head, while their leather-bound selves stayed snuggled against one another in a forgotten library where time stopped.

“Wake up,” she whispered to her slightly boisterous friend, who was draped in royal blue. She was only met by silence, laden with (what she thought) were silent, rhythmic snores coming from her friends, forming a melody that had often lulled her to sleep.

She dropped her backpack on the floor with a soft thump, opened it and took out the crumpled notes she had written secretly in geography class. The notes were covered with eraser marks. But they were also decorated with pink flowers. She slid one note inside each book, then took all of them in her arms for a group hug, as she arranged them back in the bookshelf, in an order they liked to sleep in.

Red next to yellow, who likes to stay mellow. Yellow next to blue, who likes to say boo. Blue next to pink, who never once blinks. She gave them all a pat on the back, as she wiped a tear threatening to land on her red faced friend, who would instantaneously wake up, with a questioning glare.

This wasn’t goodbye, she thought. Goodbyes aren’t one sided affairs and you can never say goodbye to something that lives in your head or breathes in and out with you, desperate for air, whenever an idea strikes you like a whirlwind, takes you on a journey to God knows where and you, unknowingly, find your way back.

Sunita picked up her backpack, as she dusted herself off, glanced at her friends and smiled like she meant it. She made her way to another secluded bookshelf, full of strangers, covered with a layer of dust.

She picked them up.

Wiped the dust.

Read their names over and over until they were engraved in her brain.

“I’m Sunita,” she whispered, and nodded, understanding that the strangers needed sleep and tomorrow wasn’t that far away. “We’ll be great new friends,” she whispered softly and tiptoed out the library, merging into the crowd of sheep.

She suddenly stopped.

She found her lungs taking big gulps of air.

She forgot she had been holding her breath all this time.

Turning strangers into friends was the best gusty wind she had ever run into.