The Oaken Chair

Published on 2013-07-30

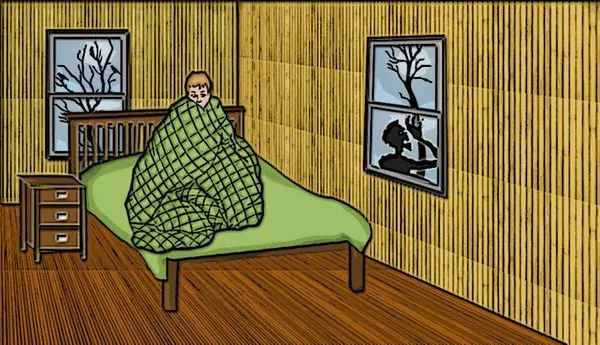

And she was sure, absolutely sure, that he didn’t mean to really hurt her or even to scare her.

He said he didn’t mean it.

They went to marriage counseling and got the number of a psychiatrist he could see and they went home. They sat in the living room on the robin’s egg blue sofa that she got when her grandparents died and held hands and she even watched one of his movies, the kind she hated with aliens and fighting and explosions, and he even went out with her to that Indian place though he always said Indian food smells funny and so do Indian people — and that was the sort of thing that they fought about, when she reminded him not to be racist and he would get so mad and tell her not to tell him what to think or say — but things seemed okay. He wanted to have sex so she had sex with him even though she wasn’t in the mood but because she thought things would mend more quickly if she did.

She decided to forget about him breaking the chair, smashing it into the wall.

She wanted to forget the fear, the rise of acid into her mouth, the feeling like she was going to vomit, the frail feeling in her knees. She decided not to think about how the chair splintered and one of the splinters hit her arm and it was so sharp, like a blade, and cut the sleeve of her blue blouse, her favorite blouse. But she didn’t throw the chair out, even though she threw the blouse out.

She went, several times, picked up the pieces, meaning to bring them out to the curb but it seemed that something else always came to her mind and she’d put the pieces back where they were, next to the microwave cart, where they kept the separate bins, white for regular garbage and blue for recycling.

The chair had been oak, a gift from her favorite aunt, and stained in a lovely dark stain which showed the grain of the hard wood.

He had said he’d repair the chair but it was beyond fixing. One of the legs was simply a jagged dagger and the back was fractured in fragments. It was a jigsaw puzzle that couldn’t be put together.

And so life returned to normal for them and they both went to work and when he started to get mad she’d remind him of the things he said in counseling and he’d calm down and say sorry. But still, she didn’t throw out the remains of the chair. Sometimes she would stand in the kitchen, her back to the sink and look at the mass of wood and think about how she wasn’t going to think about it.

Then one night she ordered in because she was tired and didn’t feel like cooking. And he came home from work, already angry.

He said he wasn’t Donald Fucking Trump and they couldn’t order out just because they were lazy. She hadn’t been thinking about the chair so she simply said it had been a hard day and she was worn-out and she’d already ordered the Chinese food so they might as well eat it and enjoy it. And when he took the little white container filled with red General Tso’s Chicken, extra spicy like he liked it, and threw it against the wall and it splattered, smearing bright orange sauce down the eggshell white wall and then pieces of scarlet chicken were on the beige carpet, she remembered.

She remembered the dread and the feebleness she’d felt and she got up off the couch and walked backwards, through the dining room, which was missing one chair, towards the kitchen and the oaken chair that was broken, thinking that seeing the chair would make up her mind to really leave him, leave him for good. But he pursued her.

They said unforgivable things; he said she was fat and she said he was boring in bed. And she told him she was leaving and that he was a lunatic, a violent lunatic and he began crying so she let her guard down and she went to the phone to pick it up and call her mother. Why, he asked? And she said she needed her mother to come over and pick her up, because she was leaving, leaving for real this time and he needed to understand this. She’d leave him the car, she said, because she wanted to be kind. But this was the end; this was the time she was going and never coming back. He reminded her that he said he was repentant, that he had cried and it was real, he was so very sorry, couldn’t she see that? But she shook her head and turned around to dial the phone, so she wouldn’t see him crying and change her mind.

But when her mother answered all her mother heard was broken breathing, a slight gurgling sound and then the line went dead, as her daughter lay on the floor of the kitchen with the jagged leg of the chair thrust up, through her back, breaking her ribs, through her malleable left lung, through her supple diaphragm and into the unfastened chambers of her heart, scarlet blood forming an almost perfect sphere around her unmoving form.