An Affective Disorder, the Doctor Said

Donal Mahoney | Monica Johnson

Published on 2016-11-07

No, Freddie can’t say he mourned when his father died and his father’s third wife found Freddie’s number and gave him a call to give him the news. His father had been responsible, worked hard, saved his money, put Freddie and his brothers through college but when his mother died and all the boys had grown up and left home, his father disappeared. No forwarding address. After a while Freddie didn’t think that much about him. So he was surprised when this widow he didn’t know called and told him his father had been hit by a truck that ran up on a sidewalk and flattened him. Declared dead at the hospital.

Freddie didn’t mourn his mother either when she had died although he had spent two years taking her to the best doctors hoping one of them would save her from cancer, not realizing that back in those years there was nothing doctors could do for a cancer so severe and caught so late, certainly not the big-time surgeon who said that he could. He was number one at a teaching hospital and wanted to fatten his mother up so he could operate on her again so all the residents and interns could watch and learn from him as he attempted to do the impossible.

His mother was terminal, the first doctor had said following the first of three operations two years earlier, but that doctor was an immigrant at a small hospital. There were bigger, better hospitals in Chicago and Freddie took her to the best in the city. Finally his mother, in her last days and when she weighed about 80 pounds, said, “No more operations.” She died two weeks later in the middle of the night right after Freddie had called the hospital to ask about her and heard the usual mantra, “Your mother’s vital signs are stable.” They never said she was dying.

But after the funeral Freddie sat for three hours and sipped Cokes in his apartment and watched a movie of his entire life run through his mind. Like Freddie’s father his mother did everything a mother could do but she wasn’t any better affectively than his father had been although Freddie would bet no mother ever made better salami sandwiches. He ate three or four at a time and took them and everything else she did for him for granted. That’s what a mother was supposed to do. He was too smart to know better.

Freddie had been a kid reared in a neighborhood of immigrants. The other kids, by and large, had parents who drank too much, fathers who didn’t work, mothers who played canasta all day and let their kids make their own sandwiches if they could find something in the refrigerator.

One kid had come to love sandwiches made with dill pickle slices and ketchup because that’s what he used to find in the fridge. There was always salami and liver sausage in Freddie’s fridge. In comparison, Freddie had it made but he was always too smart to know better.

Besides Freddie, three other boys in his neighborhood went to college at a time in life when if kids went to college their parents had to have the money to send them because there were no loans and only geniuses got scholarships. The only jobs kids could get then were paper routes on bicycles and paper routes didn’t earn tuition.

There were no fast-food restaurants where a kid could at least earn minimum wage. In fact, there was no minimum wage.

Freddie’s first job as a dishwasher in a greasy spoon paid forty cents an hour and as many hamburgers as he wanted for lunch. He always ate at least three with a milkshake. The owner’s wife didn’t like that but Freddie didn’t get fired. He was 14 at the time. It was the summer between 8th grade and high school. Who knows what they would have had to pay an adult to wash dishes. Probably a dollar or more an hour. Big money for unskilled labor at that time. Businesses paid what they needed to get the job done and often that wasn’t very much.

All the material things in life a kid could reasonably expect Freddie’s parents made certain he had on time. But otherwise they were inadequate as parents although neither they nor Freddie knew it at the time. As Freddie told the doctor much later in life, he never recalled being hugged or kissed by either one of them although perhaps as an infant one or both of them might have done that, his mother especially, he thought, because she would smile once in awhile. But hugging, kissing or smiling was not really his father’s style.

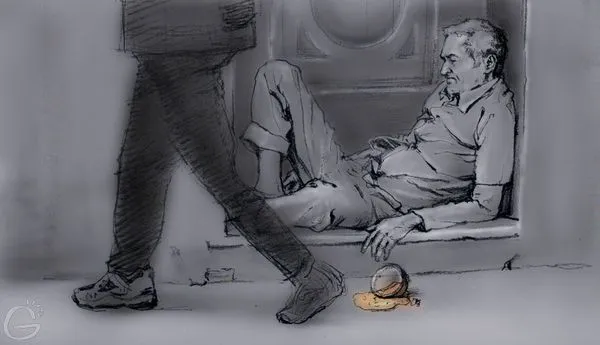

It wasn’t until much later in life, as a husband and father himself, that Freddie came to realize that when it came to love—real love—he was missing some component other people seemed to have. Not just romantic love because sex always got in the way of that. But other kinds of love—what parents felt for children, what brothers and sisters felt for each other, what grandparents seemed to feel for everyone. Freddie didn’t feel anything like that, never had and thought it was odd when he witnessed demonstrations of love in other families. Worse, he didn’t know something was missing in him until very late in life. But it was too late then. What had happened had happened and in some respects Freddie realized he was lucky to have been sent to an institution rather than a prison.

He hoped one of these doctors would be able to figure out what was the matter with him but all they had said so far was that he had an affective disorder since childhood. But even if they could help him with that it would make no difference, really. He would never get out of the institution and besides, even if he did, where at his age could he go? His kids didn’t want to see him because they had found their mother.

At times, usually in the middle of the night, Freddie felt like apologizing to everyone involved. Almost. He had more sessions to go with the doctor. Maybe something would kick in and he’d start writing letters. The doc said he’d give him the stamps if he ever wanted to do that. But Freddie didn’t feel like apologizing yet and he really wouldn’t know where to send the letters even if some day he wanted to write them. What the hell could he possibly say? Sorry wouldn’t help anything as far as he was concerned. Besides, most of the time he wasn’t sorry and he thought he should be by now.